Will the coronavirus outbreak lead to new L.A. crime fiction? The jury is out

- Share via

Steph Cha doesn’t expect much in the way of good crime fiction to spring from the coronavirus outbreak. She has lots of reasons, not least of which is that the pandemic has put a damper on crime from Los Angeles to New York City.

No crime? No crime stories.

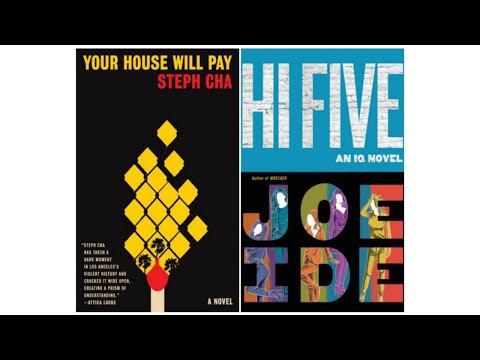

But wait until the outbreak is over, says the author of the 2019 crime thriller “Your House Will Pay” and a trilogy of L.A.-based detective novels featuring Korean American sleuth Juniper Song.

“If we come out of this, and this is an unmitigated economic crisis, and we have an unprecedented closure of small businesses, more homelessness, 25% to 30% unemployment, the post-coronavirus era could be like the Depression era,” Cha said. “That’s where noir came from.”

Here in the undisputed capital of noir, a new generation of fictional gumshoes is treading the mean streets of a very different Southern California than those first explored by the likes of Philip Marlowe. Many are like Cha’s Juniper Song and Joe Ide’s Isaiah Quintabe, millennial sleuths whose work brings them into parts of Los Angeles County rarely explored in one of fiction’s most popular genres.

And they share a common bond with Marlowe — who sprang to life in Raymond Chandler’s 1939 classic “The Big Sleep” — and with the men and women who have fought for literary justice in the decades since. They were born in times and places of economic upheaval and cultural change, of pain and disaster and deep inequality, the stuff that powers fiction.

Marlowe is a product of the Great Depression. Michael Nava’s hero Henry Rios is a gay, Mexican American defense attorney, struggling during the depths of the AIDS crisis. Isaiah Quintabe is Sherlock Holmes reincarnated as a black high school dropout navigating gang-filled East Long Beach. Cha’s “Your House Will Pay” explores tensions between black people and Korean Americans in the years after the 1992 riots.

“Noir flourishes in these hotbeds of desperation,” Cha said on the day the U.S. crested 100,000 confirmed cases of coronavirus. “The way that [2020] becomes an era of crime fiction, it’s not coronavirus fiction, it’s post-coronavirus fiction. And I hope it doesn’t come to that.”

It is, of course, too soon to tell. Years generally pass before life-shaking events and major cultural change are reflected in fiction. So don’t hold your breath for the Great Post-Coronavirus Novel. If you need proof, just check the mystery section of your library or local bookstore.

That’s where you’ll find Dave Brandstetter, the first major gay hero in a mystery novel. Brandstetter was introduced in 1970 by Los Angeles poet and novelist Joseph Hansen. He was a middle-aged L.A. insurance investigator, tough, smart and honorable.

Couch conversations: L.A. Times Book Club hosts its first virtual meetup with crime writers Steph Cha and Joe Ide.

Five years before Brandstetter premiered in “Fadeout,” the first demonstrations for gay and lesbian equality began in Philadelphia. They were called the Annual Reminders and they ended in 1969. That was the year of the Stonewall riots — days of violent protests after police raided Stonewall Inn, a Greenwich Village bar catering to gay men and lesbians.

The first AIDS case was diagnosed in Los Angeles in 1981. Two years later, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced that most cases were among gay men, intravenous drug users, Haitians and people with hemophilia.

Henry Rios hit the bookstores in 1986. Like his creator Michael Nava, Rios got his law degree at Stanford University and started out in San Francisco before moving to Los Angeles. The fictional Mexican American attorney met his lover, Josh Mandel, in book two of the Rios series; Mandel was dead from AIDS at the end of book five. Like noir heroes before him, Rios was an outsider with a credo:

“I’d gone into therapy like a good Californian,” he said in “The Death of Friends,” “and learned that in all probability the reason I’d devoted myself to the legal lepers of the world was because I felt like an outcast myself — ‘queer’ in every sense of the word — and I struggled to compensate with good works.”

And then, there’s Charlotte Justice, a complex product of the 1992 Los Angeles riots. She is a homicide detective with the Los Angeles Police Department, a black woman in a white male universe. The first Justice novel begins 48 hours into the uprising, when Los Angeles is a scene of flames and chaos. But it was published seven years after the event, in 1999.

In her four Charlotte Justice novels, Paula L. Woods brings readers a slice of Los Angeles that few are familiar with: the vibrant and successful black professional class, comfortably ensconced in neighborhoods like Baldwin Hills and View Park-Windsor Hills.

Justice is a purposeful creation, an antidote to what Woods says is the media image of African Americans in Southern California: “Blacks are going to live in South Los Angeles, and they’re going to be poor.”

The day after the CDC reported the first case of coronavirus in the U.S. — but long before the panicked run on toilet paper and hand sanitizer — Ide strolled San Pedro Street in South Los Angeles, passing homeless people lying on the sidewalk, traversing his childhood walk to school.

The west side of San Pedro belonged to the Trinity Street Gang, he said, the east side was Outlaws territory. What is now the Kaura apartments was a liquor store, where “winos used to sit out there on orange crates and drink Thunderbird all day.”

There was a prostitute named Jessie, he said, who “would show you the body part of your choice for a dollar. It took me a long time to save up a dollar. I don’t really remember what I saw, but I remember it made me dizzy.”

Ide is 62, a former screenwriter who loved Sherlock Holmes as a boy and never got a movie made. His old neighborhood is now largely Latino, but when he was growing up in the years after the Watts riots, it was black and poor. Three generations of his hard-scrabble Japanese American family lived in a rickety house on Adams Boulevard. It was torn down, he said, just before it fell down.

This intersection of Adams and San Pedro is the template for the East Long Beach neighborhood where Isaiah Quintabe plies his trade. Quintabe was 25 in Ide’s first book — titled “IQ” after its hero’s nickname and chief weapon. He’s around 29 in “Hi Five,” which was released Jan. 28. His parents are dead, his older brother killed in what first appeared to be a terrible auto accident.

He is brilliant and lonely and carries the weight of his neighborhood on his thin shoulders. “Isaiah didn’t know the statistics, but from his perspective, things were getting worse,” Ide writes in the prologue to “Hi Five.” “Not a surprising viewpoint when your job was fighting human suffering and indifference.”

Ide said he wasn’t looking to introduce readers to a previously little known corner of Los Angeles County when he sat down to write the first IQ book.

“Sherlock in the ‘hood was my only idea,” he said. “That was it. I had no aspirations to write about some great theme or to describe L.A. in a period of transition.... I wish I had aimed higher. But my aim was to write a really good story.”

That he did both still surprises him.

“A detective in the ‘hood solving problems in the ‘hood? I didn’t think that was extraordinary,” he said, “until people started saying, ‘I haven’t read a book like that.’”

Cha, however, knew exactly what she wanted to accomplish when she sat down to write the first Juniper Song mystery, “Follow Her Home,” which was released in 2013. She’d read “The Big Sleep” when she was a freshman in high school, living in Encino, shopping in Koreatown and the Korean American enclaves of the San Fernando Valley.

She wanted, she said, “to write a young, Korean American, female Marlowe, somebody with that sensibility. ... He’s kind of idealistic, and he’s constantly disappointed, and he’s a basically decent person who gets himself into situations that make him look at the world in a very embittered way.”

Cha, who is 34, stepped away from her millennial Marlowe in her latest novel, “Your House Will Pay,” which is based on the real-life killing of Latasha Harlins in 1991.

Harlins was shot in the back of the head by a Korean convenience store owner two weeks after Rodney King was beaten by Los Angeles police officers. Both incidents were caught on video. The store owner was convicted of involuntary manslaughter and served no prison time.

A similar shooting is at the heart of “Your House Will Pay,” which takes place in a racially polarized Los Angeles decades later. The Korean female shooter in Cha’s novel, Jung-Ja Han, changes her name and rebuilds her life. Her youngest daughter does not know of her mother’s criminal history.

“Other than the racist killer part, I modeled [Jung-Ja-Han] after my own mom,” Cha said. “I wanted to write a great mom who was also a racist and a killer. I don’t think those things are at all mutually exclusive.”

Cha, her husband and their basset hounds Duke and Milo have been sheltering at home since March 13. She is pregnant, due to deliver a boy-to-be-named-later on April 29. She’s been reading, walking the dogs, and watching “Fleabag” and “Six Feet Under.”

She had hoped to get a good start on her next novel before the baby is due, hire a nanny, get a nursery ready. Now she has no idea what life will look like a month from now. They may move in with her parents if the world is still on lockdown. Either that or try to be new parents on their own.

And the next novel?

“I’m thinking about writing something about Koreatown and real estate, property ownership, the surveillance era,” she said. “I need to figure out character and story, which I usually start with. Now I’m starting with themes.

“And do the themes even work? I don’t know what anything’s going to look like on the other side of this. ... This whole crisis is going to change the way we look at things like shelter and labor and basic human needs. I hope in a positive way.”

The L.A. Times Book Club hosts its first virtual meetup with crime writers Steph Cha and Joe Ide at 7 p.m. on March 30. Join the conversation at the L.A. Times Facebook Page or on You Tube.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.