- Share via

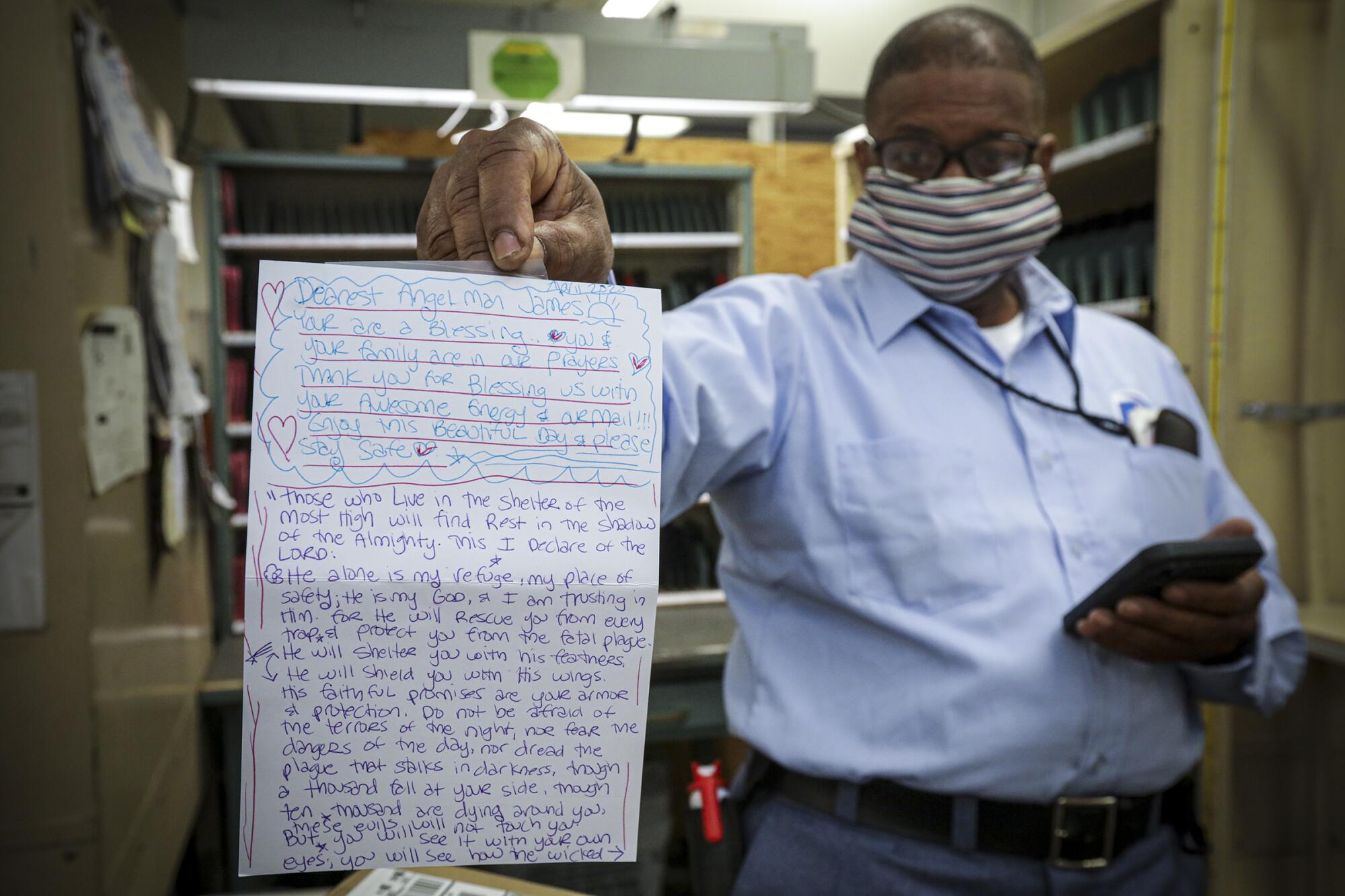

Before the start of his shift, James Daniels taped the latest note of gratitude to workstation No. 31.

In the nearly 16 years he’s delivered mail, the letter carrier has received hundreds of notes of appreciation.

But over the last couple of months, as the world changed around him, so did their tone.

In April, a month after Gov. Gavin Newsom ordered Californians to stay at home to slow the spread of COVID-19, a family along his San Clemente route wrote a note that began, “Dearest Angel man James you are a blessing.”

It included Psalm 91, a fitting hymn for this era, its words associated with times of hardship:

“Do not be afraid of the terrors of the night, nor fear the dangers of the day, nor dread the plague that stalks in darkness, though a thousand fall at your side, though ten thousand are dying around you, these evils will not touch you.”

There may be no institution more American than the United States Postal Service, which traces its roots to 1775, when Benjamin Franklin was named the first postmaster general by the Continental Congress. And yet today, in 2020, its finances are imperiled, its workers are menaced by the dreaded coronavirus and its status has been threatened by the 45th president, who in April declared, “The Postal Service is a joke.”

Customers have asked Daniels if the USPS is shutting down. One woman wrote a supportive “I <3 USPS” on her mailbox. But Daniels tells them what he tells himself: “We’ll be all right.”

He tries not to worry about top officials who are calling the shots.

“You can’t think about them up there,” the 59-year-old said. “You’ve got to focus on the people.”

::

Our postal system is older than the nation itself. And, just like the U.S., it’s had its ups and downs.

In the early 1920s, so many bandits were targeting mail trains that railway mail clerks were armed with government-issued pistols and ordered to “shoot to kill.” In the 1980s and ’90s, after a spate of homicides committed by Postal Service workers, “going postal” became shorthand for becoming uncontrollably angry, sometimes to the point of violence.

Those infamous dog attacks regularly referenced in movies and on TV? Packing a can of dog repellent is standard operating procedure.

So when the pandemic hit, it became another in a long line of challenges. As they did during the 2001 anthrax attacks, postal employees put on protective gear and kept on working.

But in recent weeks it’s become increasingly difficult to ignore the uncertainty surrounding the agency.

The USPS is projecting a $13-billion revenue loss tied to the pandemic and an additional $54 billion in losses over 10 years, Postmaster General Megan J. Brennan told lawmakers in April. At the same time, it has a longer-term burden: a mandate imposed by Congress in 2006 that it pre-fund the retirement benefits of its 630,000 employees, a requirement not imposed on other federal agencies.

The Trump administration has blocked access to a $10-billion line of credit made available in the recently enacted federal stimulus packages. But last month, a bipartisan group of lawmakers introduced the Postal Preservation Act, which would make an emergency appropriation of $25 billion and require oversight of the funding by the Postal Service inspector general.

Mark Dimondstein, president of the American Postal Workers Union, said the agency finds itself on a precipice.

“The post office belongs to everybody,” he said. “If there’s not genuine relief … then the whole question of whether the post office as a public entity can continue to serve the people on an equal basis is going to be up for grabs probably by early fall.”

Not if James Daniels can help it.

::

“The man upstairs blessed me with this job, so I’m going to go out there and do the best I can. ... I’m going to keep doing it until the candle burns out.”

— James Daniels

On a recent Friday morning, Daniels observed a series of pre-delivery rituals. He reached down and gripped his knees below his cotton shorts, stretching near a fleet of blue-and-white Postal Service trucks. There are about 800 addresses on his route, one of the longest in the office. He didn’t want to pull a muscle.

At 10 minutes after 9 a.m., he wheeled out an orange hamper loaded with packages — from Target and Staples, from Macy’s and Ulta Beauty and Amazon Prime — that clerks began sorting hours before the sun rose. They were destined for his truck, where Daniels arranged them by street, before heading back to his workstation to sort the mail. He wore his black reading glasses as he rapidly scanned the letters.

Memory is key in this job. For his USPS entry test, Daniels had to look at 100 addresses and, on the next page, identify the ones he remembered (he recalled getting 80). Over time, regular carriers like Daniels can deliver just by reading the name.

Daniels’ voice radiated warmth as he joked with his co-workers. His fellow letter carriers call him “funny man” and “King James.”

“Appreciate you guys,” Daniels called out to the clerks, as he grabbed a bag filled with small parcels.

With more people sheltering at home and ordering items to be delivered, the post office is now handling more packages than around Christmastime — the peak season, which typically lasts for only four weeks. Letter carriers are delivering gifts and cards for virtual birthday parties, food and flowers, toilet paper and bleach, as well as countless tokens of love and friendship sent by parents and children and friends who can’t be there in person.

When Doug Reid, a clerk who arrived at 3:15 a.m. to begin sorting mail, shouted that the last batch of parcels was ready, a cheer rang out among the workers.

Shortly before 11 a.m., Daniels was ready to start his route. He wore the red, white and blue mask a customer had given him for protection.

Before he left the parking lot, he read the Scripture that rested above the sun visor of his truck: Psalm 91.

::

Walking the hilly streets of his route, Daniels was a vision in blue: hat, shorts, long-sleeve shirt and gloves.

Residents and business owners greeted him by name. A physical therapy office left him a note with three Kind bars: “We appreciate your joy-filled spirit that walks in here every day.”

The changes in the city were noticeable. Closed offices. Restaurants boasting takeout and delivery. Customers telling Daniels over and over to “be safe.”

“I haven’t seen you in forever,” Daniels said to one woman.

“I can’t spend any more time with those teenage kids at my house,” she replied. “I’m coming back to work.”

“I don’t blame you,” Daniels said, with a laugh. After raising three kids, he understood.

He greeted his people by name. In 16 years, he’s seen young men and women he knew as children head off to college, he’s been introduced to significant others and he has grieved for longtime customers who died.

Daniels emulates the letter carrier who — decades ago — inspired him to pursue this career. The postal worker joked around with his grandmother nearly every day on her porch in Flint, Mich.

Daniels’ grandmother trusted the mailman completely, clipping her outgoing mail to the box with a raggedy clothespin. When she quizzed him the next day, he’d name everything he picked up.

“This guy was just like the coolest dude ever to me,” Daniels said.

Although he joined the military at 17, and ultimately spent 26 years in the Army, Daniels never forgot that letter carrier or the importance of the profession.

There are more than 31,000 post offices and 630,000 postal employees across the country. On a typical day, they process and deliver 471 million pieces of mail to nearly 160 million delivery points, according to the agency. A recent Pew Research Center survey showed that 91% of respondents have a favorable view of the USPS.

The Postal Service has long served as an entry point into the middle class for African Americans; around a quarter of the agency’s workers are black, according to the Pew Research Center. And, as of 2018, the agency employed more than 100,000 military veterans, according to Pew.

“The man upstairs blessed me with this job, so I’m going to go out there and do the best I can,” Daniels said. “I’m going to keep doing it until the candle burns out.”

Daniels knows how important the Postal Service is, especially at a time like this.

So do his customers.

::

When Daniels reached Avenida Serra around 1 p.m., residents were gathered in the street waiting for a U.S. Air Force Thunderbirds flyover honoring front-line COVID-19 responders and essential workers.

“All you’ve got to do is look up,” Traycee Taylor Greene told Daniels. She’s lived on the street for 30 years, and every Christmas she gives baked goods to Daniels.

Daniels receives so many treats that time of year that he’s had to turn people down or put the sweets in the post office break room for everyone to share.

Because of the virus, Taylor Greene said, she planned to put together another package for him.

Across the street, as Daniels dropped off the mail, Todd McMeill reminded him about the jets.

Column One

Column One is a showcase for compelling storytelling from Los Angeles Times

The longtime resident likened Daniels to Mr. McFeely, the energetic deliveryman on “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood,” who was known for his catchphrase, “Speedy delivery!” Daniels’ normal stride, McMeill said, “is about 18 miles per hour.”

McMeill, who once worked for the post office, calls Daniels the “No. 1 ` mailman.”

“I’ve been in the industry, and they don’t get any better than that guy,” he said, describing letter carriers as “unsung heroes.”

McMeill joined Taylor Greene in the middle of the street, making sure to stay physically distanced. Both of them stared up at the cloudless sky, waiting for the Thunderbirds to make their appearance.

“I’d be happy with a rogue balloon flying by,” McMeill said. “Give me something.”

“Something in our lives!” Taylor Greene shouted at the heavens. “Help us!”

Daniels kept his eyes trained on his route, ducking into apartment complexes and behind fences. As he walked, his postal shoes shining from his morning polish, he sang Dean Martin’s “Tiny Bubbles.”

There was a Band-Aid on his right leg, applied after he’d been pricked by some rose bushes while delivering mail. Other times, he’s had to bandage cuts on his knuckles from ragged mailboxes.

Back at his truck, Daniels wiped down his hand brake, steering wheel and blinkers with disinfectant wipes given to him by a customer.

He kept a laminated handout from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the back of his truck as a reminder to be careful. More than 1,000 postal workers have tested positive for COVID-19 and at least 61 have died. Before Daniels moved on to his next stop, he changed his gloves for a third time.

After all, he observed, the two dirtiest things in the world are “mail and money.”

Daniels, focused on his deliveries, never heard the jets.

::

Hours into the day, Daniels pulled down his mask to take a breath.

After walking up steep inclines under a relentless sun, the mask was getting to him. But it was nothing, he reasoned, compared to his time in the Army, when he ran in 100-degree weather wearing an M17 gas mask.

“He knew I was going to do this,” Daniels said, pointing up at the sky. “So he got me ready for it.”

Daniels falls back on his faith often, especially when conversation turns to the challenges facing the Postal Service. He avoids reading about the issues, but at times his customers will ask him if his employer is going to survive.

“If we didn’t do this every day, there’d be a whole bunch of chaos in the world going on,” Daniels said. “I look at people up above that don’t have a clue, that ain’t down here doing nothing — they can make all the comments they want to make, but guess what? I just let them keep talking. I’ll keep taking care of my people.

“You’ve got somebody waiting on their check, somebody waiting on their medicine, somebody waiting on a birthday gift,” he said. “These are people’s lives you’re putting in their mailbox.”

Daniels, who thanks God every morning when his feet hit the floor, has faith that a higher power will make everything right.

The Scripture he’d written in his journal that morning was a comfort:

“God is not unjust; he will not forget your work and the love you have shown him as you have helped his people and continue to help them.”

::

Route 31 is Daniels’ town, and he’s the sheriff.

Over the years, he’s seen it all. A boa constrictor coming down the steps of a home on Avenida Miramar (that house didn’t get mail that day); a bee swarm that sent him fleeing to his mail truck; and three dog attacks in one day.

“You’ve just got to be aware of what’s out here,” he said.

By 5:16 p.m., Daniels estimated he’d made close to 700 deliveries. He drew energy from the half bag of peanuts he’d eaten for lunch. But after nearly two decades, his body had conditioned itself to his routine.

Someone once asked him how far he walked every day.

“I don’t want to know that,” Daniels said, with a laugh.

As he hit his final homes, Daniels greeted a circle of five people sitting in their driveway along Marquita. It was happy hour, they joked.

He pointed out their dog, his favorite on the route.

“Is there a paycheck in there?” a resident called out to Daniels, as he dropped mail in their box. “All right!”

“You guys have a good evening,” the letter carrier responded.

“Have a great weekend,” one of the men called out to Daniels, who wouldn’t be off for another five days.

Daniels cracked a smile. Gave them a wave.

“See you tomorrow,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.