WEAVERVILLE, Calif. — On the first day of school at Weaverville Elementary, third-grade teacher Saundra Murphy asked the 14 boys and girls in her class if anyone could define the phrase “social distancing.” A hand shot up in the back of the room.

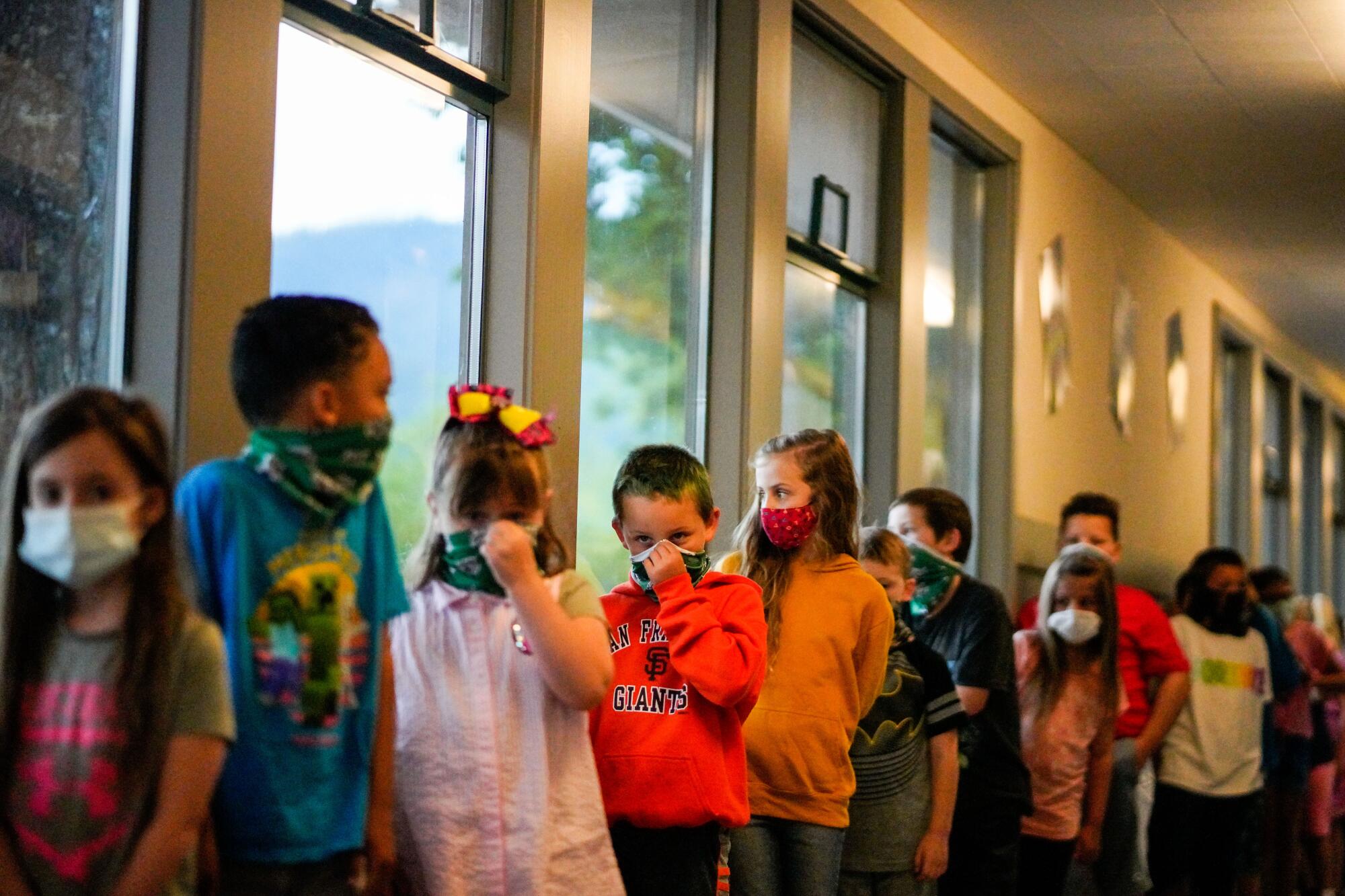

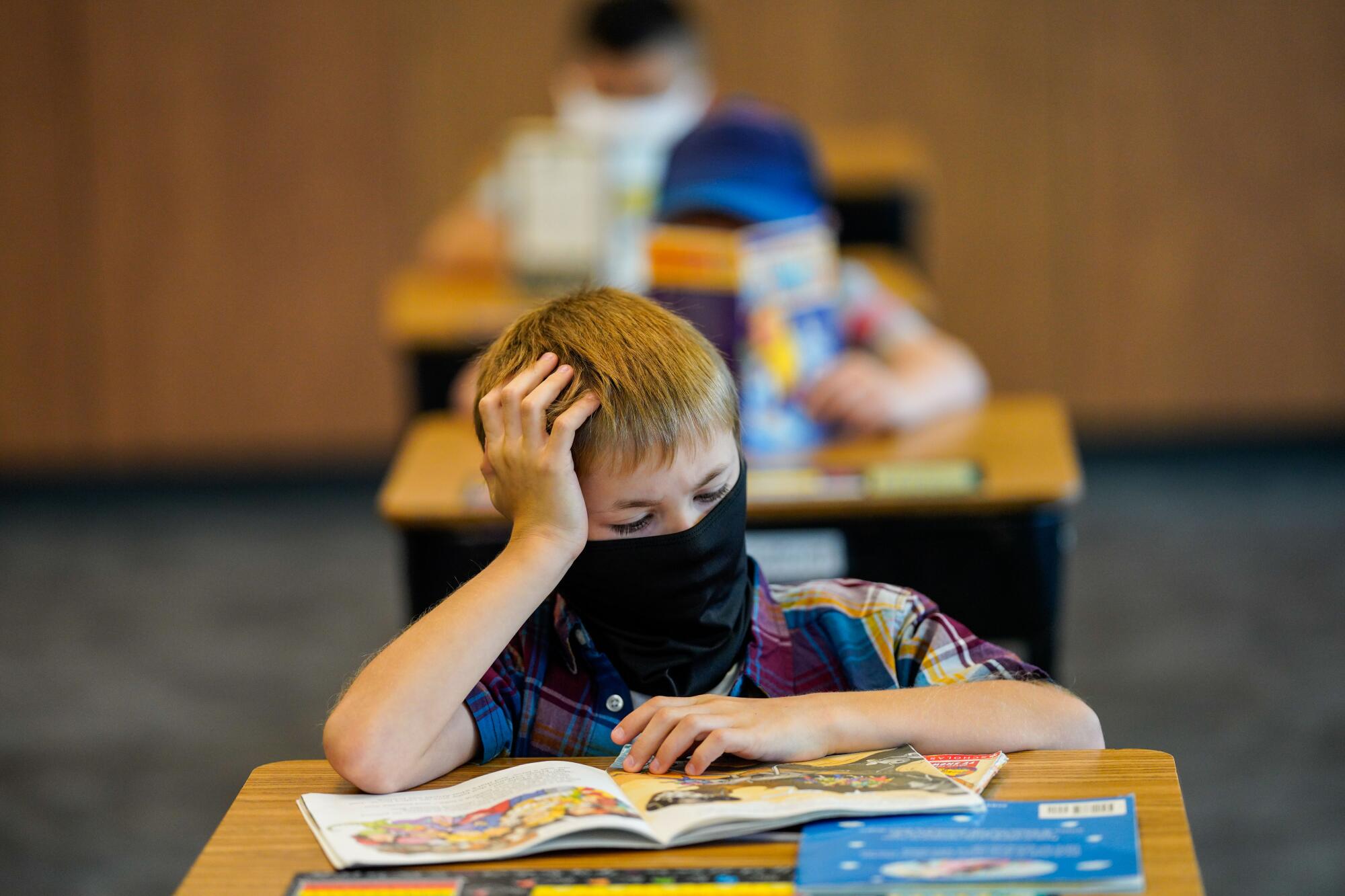

“Social distancing means staying 6 feet or more away from each other,” said a boy in a “Minecraft” T-shirt, his voice muffled by a camouflage face mask.

“Does that mean we don’t like the person?” Murphy asked last week. The students shook their heads.

“Does that mean we’re just trying to be safe and respectful of our situation?” They nodded.

While the vast majority of California students are starting the academic year online, something extraordinary happened in this public school district in rural Northern California: Students sat in classrooms.

With the region’s low case count, school administrators and teachers said they are confident they can reopen safely and quickly adjust if infections emerge. If the district is successful, it could be a preview for other California schools, including in Los Angeles County, as infections begin to decline.

The start of in-person instruction in the Trinity Alps Unified School District felt both surreal and comfortingly routine, an act of desperate, fragile hope five months after the COVID-19 pandemic closed campuses across the Golden State.

In Darsi Green’s second-grade classroom, 7- and 8-year-olds watched a “Baby Shark” cartoon with brightly colored sea creatures singing: “So-cial di-stancing! Every day! ... Even if you meet your closest friend, no handshake, just a friendly wave!”

A 7-year-old boy — who said he got really good at the video game “Plants vs. Zombies” this summer but was super excited to come play with his friends at recess — pointed to his school-issued neck gaiter with the Weaverville Elementary School Wildcats mascot.

“I like this mask because my favorite color is green, and this is green,” he said.

On the playground, Lisa Saulsbery, a first- and second-grade teacher whose blonde bangs hung over a plastic face shield, giddily shouted the names of children she hadn’t seen since March. As they ran toward her, she stopped them from hugging her by stretching her arms wide and patting the air, yelling: “Air hug! Air hug!”

Her students were more fidgety than normal after five months outside the classroom, but they seemed to understand that they have to follow new rules.

The district was allowed to open classrooms because it is in Trinity County, which has never been on the state’s coronavirus watch list. Under state rules, a school can resume in-person instruction if its county stays off the watch list for 14 consecutive days.

Since the start of the pandemic, 10 cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed in mountainous Trinity County, which lends itself to natural social distancing with 12,300 residents spread across an area bigger than the states of Rhode Island and Delaware.

In Trinity County — where there are no incorporated cities, crowded shopping malls don’t exist, and the planned installation of the county’s first permanent traffic light irked people who said it’s an unwelcome sign of big-city life — the return of hundreds of people to school campuses presents the biggest risk yet for the spread of the coronavirus.

Across the state, school closures and distance learning have exacerbated the deep educational disparities faced by students of color and low-income students. In Trinity County, which is 82% white, about 22% of people lived in poverty before the pandemic — nearly double the national average.

Around 64% of the district’s students officially qualify for free or reduced-price meals, but administrators think the percentage is actually higher.

This is a place with an independent streak, an old logging community where people bristle at government regulation and fly the green “double-cross” flag of the State of Jefferson, a proposed new state carved out of California’s rural, conservative northern counties.

“The bottom line is, what you can’t see will kill you. We all like what’s tangible. We want to see the great white shark coming. That’s going to eat me. But what’s way more dangerous is all this microscopic garbage floating in the air.”

— Jaime Green, Superintendent of Trinity Alps Unified School District

After schools closed in March, many isolated students here battled apathy and anxiety, witnessed increased drug and alcohol abuse by their parents, and fought more with their stressed-out families, the county noted in its school reopening plan. As in other rural areas, the district struggled to teach far-flung students who have less access to the internet and bad cellphone service and who rely on schools to feed them.

“There’s a lot of despair,” said Sheree Beans, the school nurse for the Trinity County Office of Education who helped write the schools’ reopening plan. “I feel like COVID took away hope, and that lack of hope, it spans generations.”

Even before the pandemic, it had been a difficult year. In June 2019, the county shut down the campuses of Weaverville Elementary and Trinity High School after the discovery of toxic black mold. The district gutted both schools, which were also filled with asbestos tile. Students got used to seeing people walking into their old classrooms in hazmat suits while they learned in portable buildings.

Then came COVID-19, which preys on the lungs, exacerbating the same respiratory conditions that mold does.

“The bottom line is, what you can’t see will kill you,” Supt. Jaime Green said. “We all like what’s tangible. We want to see the great white shark coming. That’s going to eat me. But what’s way more dangerous is all this microscopic garbage floating in the air.”

Green is a relentless optimist, but that didn’t make him any less stressed about the first week of school. He hadn’t slept much. A 16-ounce Red Bull stood on his desk.

Of the financially strapped district’s 700 or so students, just over 100 are starting remotely, Green said.

“We are prepared for, if we get shut down and we quarantine, we will distance learn for 14 days,” he said. “Then we will come back to school, and we will do it again, and again, and again.”

The first day of school started at 5:06 a.m. Monday for bus driver Carl Treece, who drives a 104-mile round-trip mountain route on State Highway 299 — one of the longest in the state.

Treece left the Weaverville bus barn before sunrise in his own car, coasting around hairpin turns and narrowly missing two deer. In the past, his route has been obstructed by boulders and black bears.

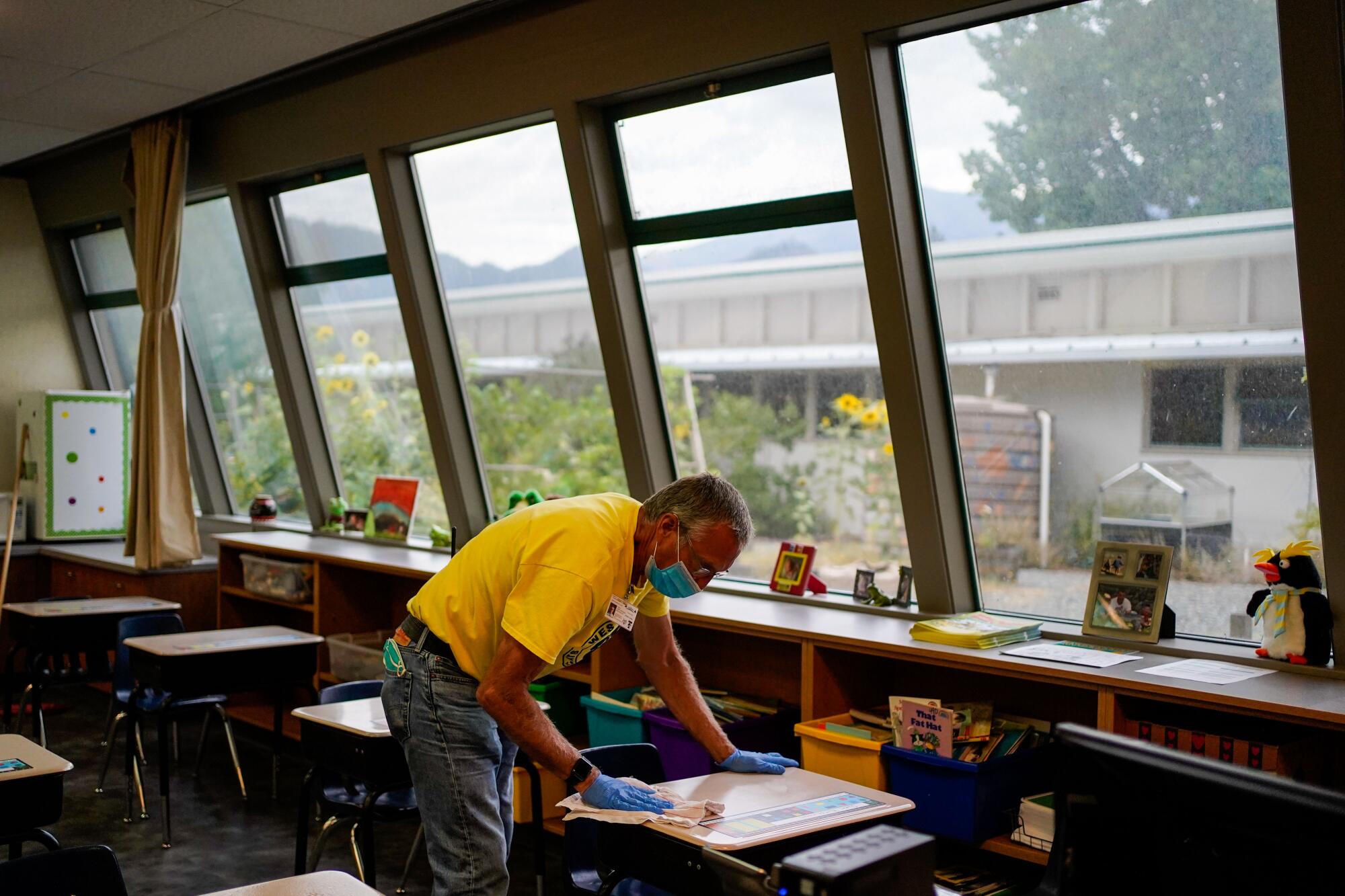

Treece picked up Bus No. 6 at Burnt Ranch Elementary School, which recently rebuilt after it, too, was found to have toxic mold. Treece sprayed the bus seats with a bottle of pink-colored disinfectant before finishing the drive to his farthest stop.

After schools closed, Treece kept driving this route to deliver meals and homework packets. He worries about the students keeping on their masks — required for all students third grade and older, recommended for those younger — when it gets hot. There is no air conditioning onboard.

At 6:47 a.m., he made his first bus stop at a boarded-up restaurant called The Whole Enchilada in the minuscule town of Salyer, and picked up three high school boys.

Billy Atkission, a 17-year-old senior from Willow Creek, got up at 5:30 for his mom to drive him to the bus stop. He’ll have to get used to waking up early again, he said from behind a black cloth mask.

“I finally get to see these dudes after five months,” he said, nodding at the other boys. “I haven’t seen anybody at all, just because everybody I’m friends with lives so far away. I miss my friends a lot.”

He added: “I’m not really worried about the corona. Not that much.”

As the bus pulled into Trinity High School at 8:06 a.m., Treece said: “Do your part to prevent the spread. Right? Wear your masks at all times on the bus. Do your social distancing. ... Anybody wanna place any bets on how long we’ll be able to stay open?”

“A month!” one boy shouted.

“Better be forever,” yelled another.

In the hallway before classes began at Weaverville Elementary, Principal Katie Poburko cheerfully greeted a third-grade boy in a blue surgical mask. He pinched his nose and said he didn’t like it.

“You have something else you could try,” she said. “It’s called a shield.”

“A shield?” his friend interjected. “A Captain America shield?!”

A few hours later, Poburko spotted a boy standing alone outside his fifth-grade classroom, breathing hard. He had gotten hot and overwhelmed in his red face mask. He smiled shyly as she brought him a face shield.

At 10:58 a.m., the transitional kindergarteners filed into the cafeteria, where a masked and gloved cafeteria worker stood behind a clear sheet of plastic and handed each child a lunch — peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, strawberries, carrots and Cheez-Its — to eat outside.

Darsi Green’s class sat cross-legged and far apart on the basketball court. A chorus of silly songs bounced between them: “Pea-nut butter jell-y time! Pea-nut butter jell-y time!”

On the playground, a boy with a green neck gaiter pulled over his whole face danced around a tetherball pole with the ball removed. A girl in a lacy maroon dress, pink cowgirl boots and a pink cloth face mask giggled as she chased her friends.

As the students played outside, maintenance worker Aaron Gonzalez disinfected their classroom, wiping desks and doorknobs.

After class, teachers gathered in the gym to discuss what worked and what didn’t. They would need more outdoor lunch tables. And the playground games of basketball and wallball would have to be nixed out of concern so much hand-to-ball contact could risk the spread of infection.

Give lots of praise for following rules, Poburko suggested. And give the kids time, “to talk about how mad or scared they are.”

At Trinity High School the next day, students wore masks in the classrooms, but many pulled them down as they hung out in the schoolyard during lunch. They are still learning out of portable buildings while their campus is still being rebuilt.

Many students figure it’s just a matter of time before they get shut down again. After what happened with the mold, they’ve gotten used to the school year being upended and high school rituals being lost. Fall sports have already been postponed until at least January.

“The mold felt like the end of the world, and then all this happened and it’s so much worse,” said Tyler Sprague, a 16-year-old senior who spent the last five months mostly isolated out of concern for his grandmother’s health.

“Last year, when we walked into those portables, I remember thinking, ‘This is gross,’” added his friend, Kylee Scribner, a 16-year-old senior. “But now? I’m just grateful we’re here. Now, I’m like, OK, portables? A classroom? That’s better than virtual.”

Scribner joked that, some day — “if the world doesn’t end” — she’ll get to brag to her children that she survived a pandemic and a high school full of toxic mold.

This week, hanging on to tradition while they can, the senior class gathered on a mountaintop to watch the sunrise. Coming back down for class, Tesla Ehlerding, 17, she felt at peace about this year, no matter what happens.

“It might not be ideal, but this is what we have,” she said. “I think we’re lucky, despite all the bad.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.