Column: California could soon end its dumb policy on inmate firefighters. What took so long?

- Share via

All it would take is one phone call from a fire department. Any fire department.

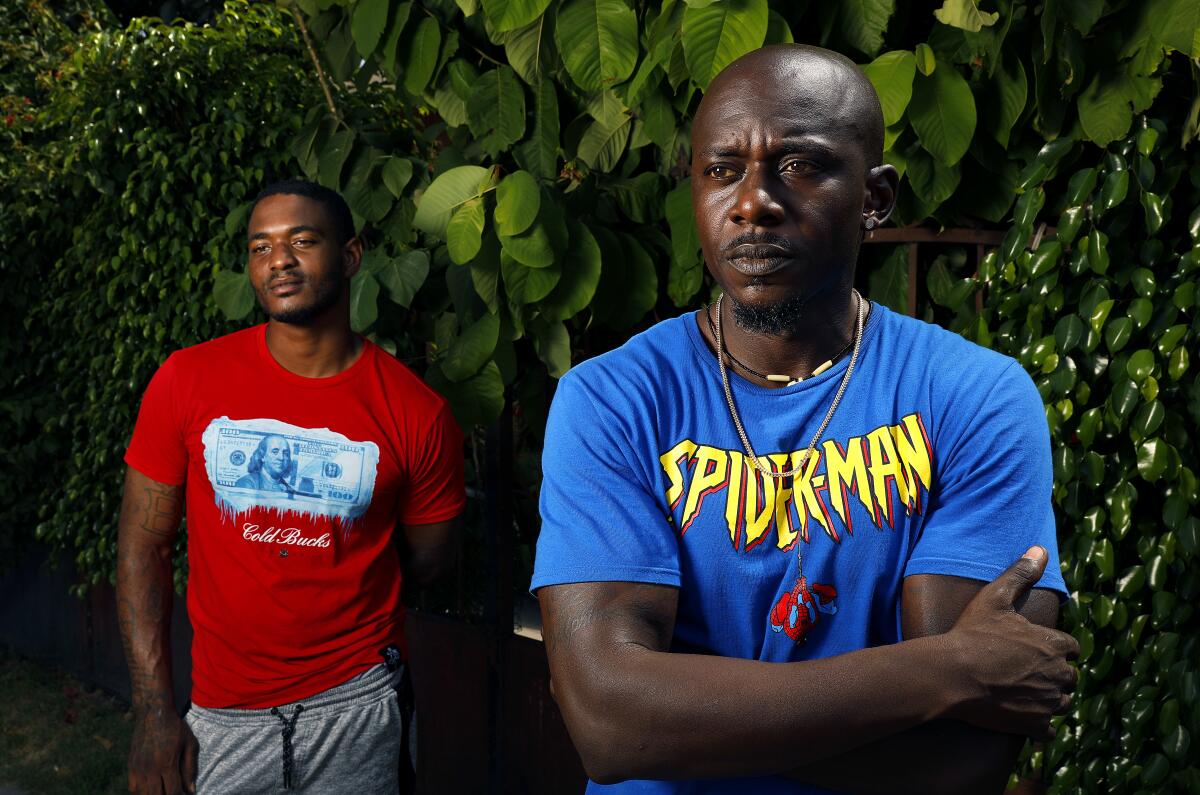

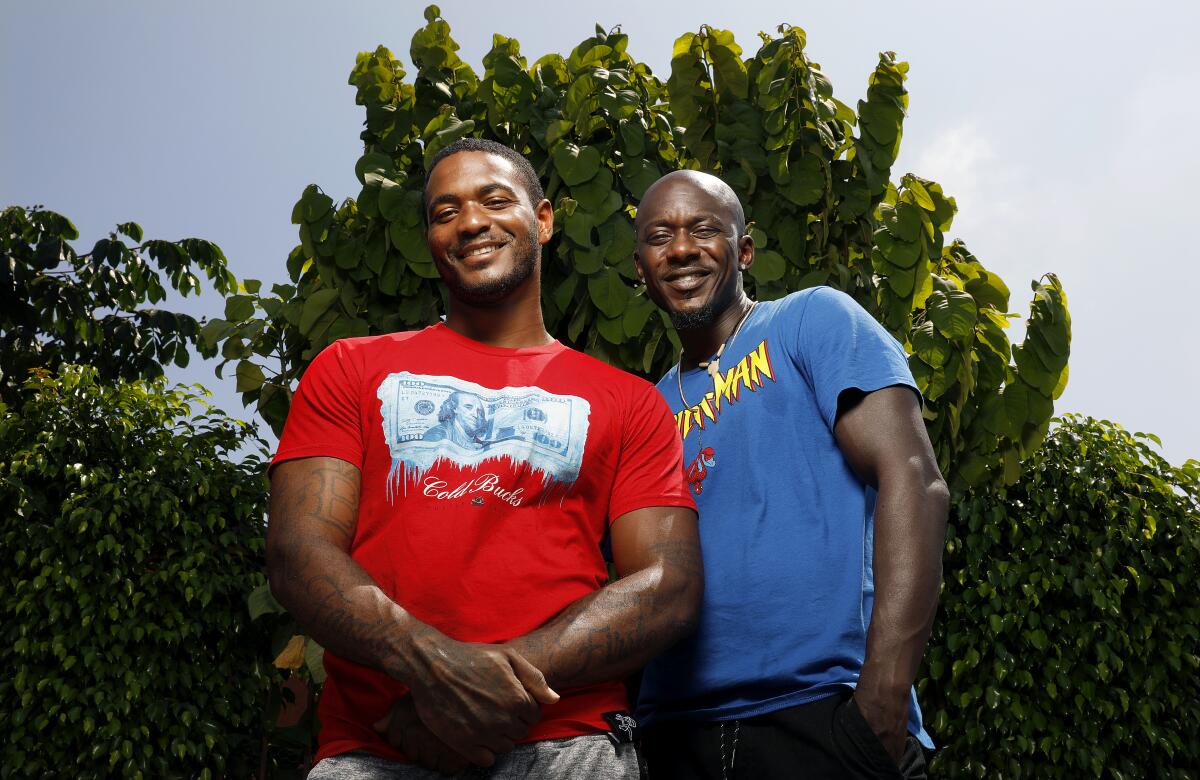

Joshua McKinney assured me of this one recent morning, standing in the shade in his grandmother’s driveway in South Los Angeles as an LAPD helicopter circled overhead.

For weeks now, ever since the 26-year-old got out of prison in June, he has been trying to earn a paycheck in an economy that’s in shambles and dreaming of returning to the fire lines, where he worked to get months off his sentence, earning a pittance.

“I went in mainly to get out early, but as I was there, I actually fell in love with it,” McKinney explained. “I was like, ‘Dang, I never knew how much I loved hard work.’”

He and thousands of other Californians are barred from suiting up again because of their criminal records, and that is just stupid for a state that is woefully short on resources to fight fires. In recent weeks, firefighters have been overrun in Northern California, slammed from all sides by wildfires that have killed at least seven and scorched what’s already topped 1.4 million acres.

Thankfully, this could soon change.

After years of pushing, mostly by Assemblywoman Eloise Gomez Reyes (D-Grand Terrace), the Legislature on Sunday night sent a bill to the governor’s desk that would help former prisoners — most of them Black and Latino — to earn the emergency medical technician license necessary to become full-time, year-round firefighters with the state, and numerous counties and cities.

Under AB 2147, former prisoners who have successfully worked in one of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s fire camps will be able to petition a judge to quickly expunge their records and waive parole time. They then would be able to apply not only for an EMT license but a host of other licenses required by other professions.

Logical, right?

All it took was a bit of creative policymaking to please the firefighters’ union, a pandemic that has emptied prisons and fire camps alike, an early wildfire season that has already destroyed scores of homes in Northern California, an eye-popping unemployment rate, and nonstop protests over the long-standing racial inequities of the criminal justice system.

That said, it shouldn’t have taken all of these compounding catastrophes to summon the political will to right one of California’s most notorious wrongs.

We use thousands of prisoners to do the grunt work of fighting fires, pay them a slave wage to do it and then, when they get out, we refuse to offer them a job doing the same thing for an actual living wage with benefits. And then we have the nerve to crow about our progressive values on criminal justice reform. Meanwhile, the state’s recidivism rate remains “stubbornly high,” averaging 50% in the last decade, according to a recent state audit.

Even the Los Angeles Lakers took California to task over this hypocrisy last week, issuing a rare tweet in support of then-pending legislation from Reyes.

“We know that these incarcerated firefighters have already demonstrated a commitment and desire to turn their life around,” Reyes said, noting that corrections officials preemptively weed out prisoners who have committed serious offenses, such as rape, or have a history of escape with violence. “I would hope that most of us would agree that an individual willing to face down a fire and smoke is much more than the sum of their previous mistakes.

“I don’t want a sentence that has been completed to become a life sentence. And unfortunately, our criminal justice system has done just that. Even after somebody has completed their sentence, they’re living a life sentence, because so many doors are shut to them.”

This is something McKinney is quickly coming to understand. Now that he’s out of prison and on parole, he has applied for one of the few spots in the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection’s Firefighter Training and Certification Program, run out of the Ventura Conservation Camp. Launched a couple of years ago, it helps people with criminal records compete for entry-level firefighting jobs with state, federal and local agencies.

For well over a week, hundreds of inmates have chain-sawed through relentless thickets of chaparral, cutting lines through the backcountry to thwart the fire’s sudden rushes at homes.

In the meantime, though, McKinney is at a bit of a loss about what to do with himself.

“I’m just, I don’t know,” he said with a shrug. “Well, I’m not gonna say I don’t know. I know what I want to do. But I don’t have the proper certifications.”

McKinney’s friend, Eric Hunt, went through a similar experience when he was released from prison after a stint in a fire camp.

At first, Hunt tried to get a job at fire departments, only to find out that he couldn’t, he said. Then he landed a job doing recruitment for a jobs program for at-risk youth and veterans. Then one of his bosses found out he was on parole and Hunt, who grew up in Pomona and now lives in Altadena, said he was let go.

So now Hunt has joined the ranks of Californians looking for steady employment in an economy turned upside down by the COVID-19 pandemic. Nearly 4.8 million people in the state are collecting unemployment benefits. The most recent figures, according to the U.S. Labor Department, showed 209,500 initial claims during the week ending Aug. 22 — a number that is going up, not down.

To make ends meet now, Hunt does a little of this and a little of that, he said. A natural salesman with a quick wit and a tendency to talk in inspirational koans — “Like my uncle told me, you ain’t had a best friend ‘til you been one” — he sells fruit cobblers at farmers markets and wants to teach paint-and-sip classes once he finds the right outdoor location.

But what he loves to do is talk about wildfires and about fighting them, usually with full-on reenactments and sound effects.

Like the time Hunt was ordered to help set a controlled burn. It was the first real wildfire he had experienced.

“I didn’t know fire grew so fast and could get so hot. And I’m like, man, back of my neck is hot. And I look and there’s just this wall of fire there — 200 feet in the air, just fire. All of this air starts to whip these trees around and I’m like, oh my God.”

He just started running.

“I’m swinging my arms, and I’m flinging fuel all behind me on the bushes. I finally burst through the other side. And there’s everybody, and they all start falling out laughing because I look panicked. My hard hat is on sideways, my goggles are down around my neck.”

Or the time during the Woolsey fire that he had to help a member of the crew down Boney Mountain in Malibu.

“He’s tired, his legs are wobbly. I take his tool from him, which was a shovel. And he grabs the top of my backpack, and I slowly start to descend.”

McKinney has plenty of stories, too. Like the time he and his crew had been working for hours in the heat, hacking away at brush and trees with packs of heavy gear on their backs, when another wind-whipped blaze suddenly erupted in the distance.

“I’m just standing and I’m looking at it. You can kind of see the smoke start to rise and rise. I felt the wind start to pick up because,” he said pausing for emphasis, “you’ve got to be aware of the wind directions on you at any moment.”

Soon, McKinney said he was bent over once again, clearing brush with a chain saw — only this time, in the face of 30-foot flames.

“I never sweated that much in my life,” he said.

Both McKinney and Hunt credit their time in fire camp with teaching them to be better human beings. They speak with pride — and a bit of surprise — about the residents who have offered thanks and food and water for saving their mansions. They brag about how they moved up the ranks of their respective fire crews.

For Hunt, in particular, who has been in and out of police custody for a variety of crimes since he was a teenager, the fire camp experience was life changing. He said he became a person whom his mother could once again be proud of.

“You become an entirely different person from who you were,” he said. “So it’s difficult. I’d love it if they just said, ‘Hey, come on down and report.’”

All it would take is one phone call — and the promise of a salary that actually befits a firefighter. Not even the risk of contracting COVID-19 is a deterrent.

“Just give us two radios,” McKinney said, as Hunt nodded. “We’ll make it happen.”

First Gov. Gavin Newsom has to make it happen and sign AB 2147.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.