Fall in Southern California begins the race between rains and Santa Ana winds

- Share via

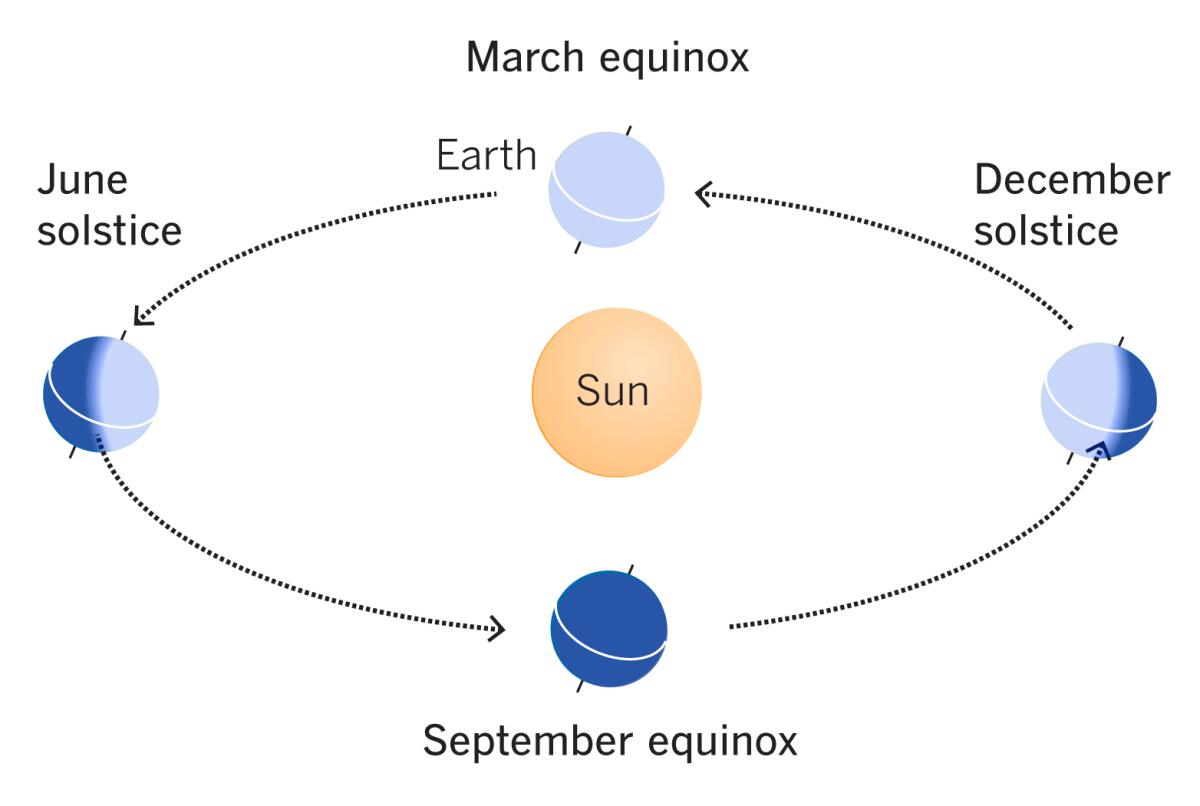

The autumn equinox was at 6:30 a.m. PDT on Tuesday, meaning there are nearly equal periods of daylight and darkness. From now until the winter solstice in December, days will gradually get shorter and nights will get longer in the Northern Hemisphere.

That’s good news and bad news for fire-scorched California.

The good news is that as the Northern Hemisphere tilts farther from the sun, the sun’s rays are less direct, and cooler daytime temperatures result, along with cooler nights. The arrival of the rainy season is usually in about November.

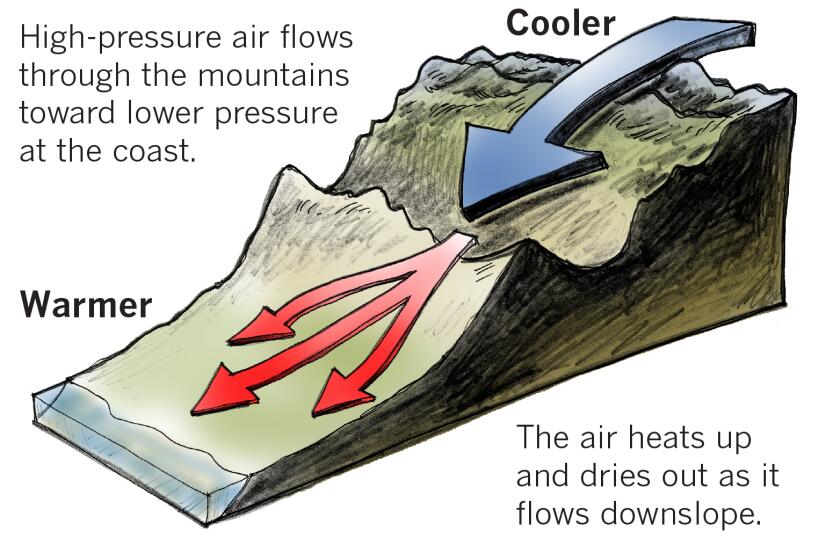

The bad news is that October to November are the peak months for the Santa Ana winds. These strong, often hot, downslope winds can lower humidity to single digits and cause extremely dangerous fire weather conditions.

“Every fall, Southern California hosts what I call the annual Santa Ana-rain race. Which will arrive first, the Santa Anas or the rain?” said climatologist Bill Patzert.

After an apocalyptic fire season thus far, Californians have heat wave and fire fatigue, “but there are another two months of drama ahead,” Patzert said. “If you think the season is bad now, just wait!”

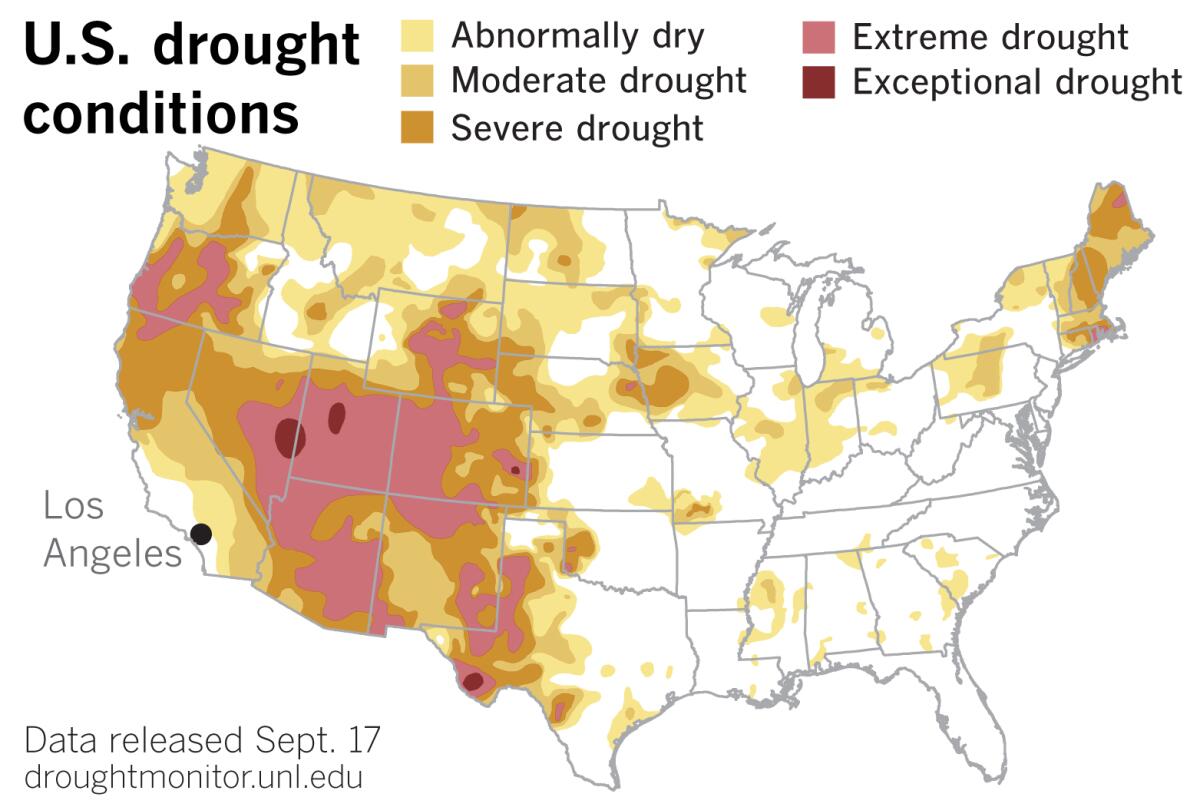

Although not a perfect picture, the most recent U.S. Drought Monitor, released on Thursday, provides “an ominous visualization of the conditions that set us up for fires,” Patzert said.

The map shows an intensification of the drought in the West after a heat wave that set the stage for wildfires that consumed thousands of acres and degraded air quality. Late summer was a time of record heat that peaked on September 6 with the hottest days ever recorded in California locations such as Woodland Hills (121 degrees Fahrenheit), Paso Robles (117) and San Luis Obispo (117).

Other places in the Southwest recorded unusually high temperatures, and soil moisture plummeted even as the eastern edge of the West received rain and early-season snow. However, according to the Drought Monitor, the rain and snow merely staved off further drought intensification

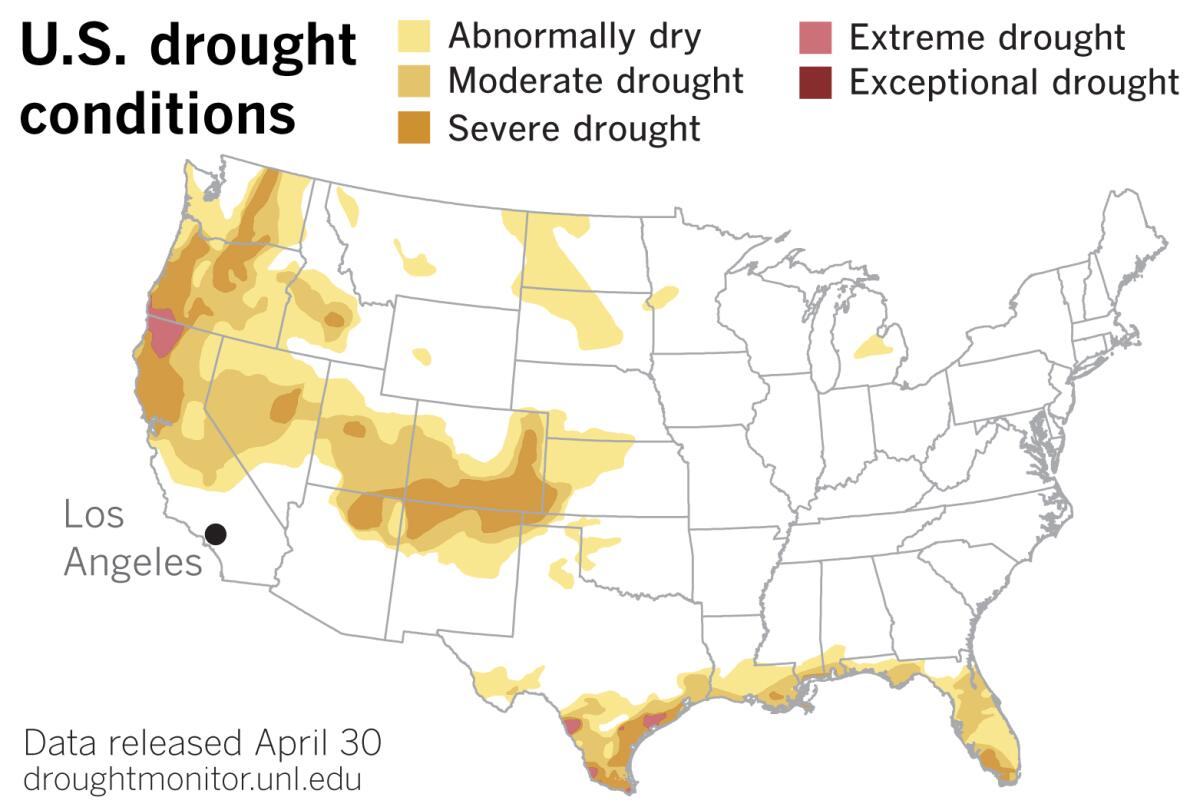

Even before the Santa Ana and Diablo wind seasons begin in California, the dramatic expansion of the Western drought is clearly illustrated when the current drought map is compared with the Drought Monitor released on April 30. Northern California, which had a late-starting and disappointing rainfall season, was already suffering from drought in the spring, but Southern California, which saw some unusual late-season soakers, was not yet affected by drought — although normal conditions in the southern part of the state are generally dry and fire-prone.

The most dramatic expansion of drought is seen in the Pacific Northwest and the Southwest. Large portions of Oregon, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, Arizona, New Mexico and West Texas are considered to be in extreme drought, and some areas, especially in Utah and Nevada, are classified as in exceptional drought.

The monsoon season, during which some parts of the Southwest expect to receive about half of their moisture, has been a no-show this year, making for an historically dry summer.

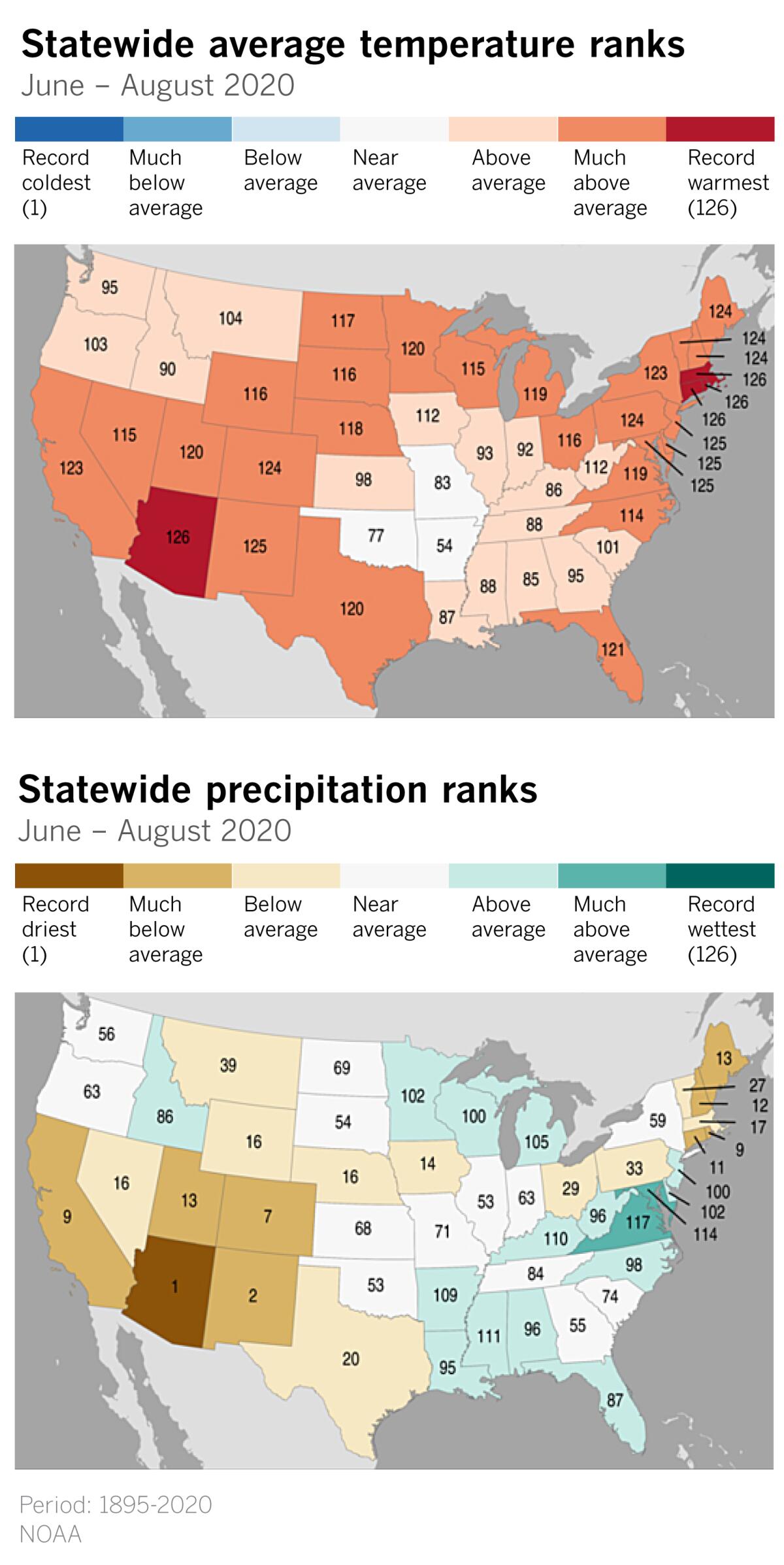

“Over the past 126 years, Arizona has never experienced a hotter or drier summer,” said Rob Howlett, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Tucson. “These two elements are highly correlated, because without cloud cover from afternoon thunderstorms, the state bakes under intense high pressure.”

“September rainfall is heavily influenced by tropical cyclones that move up the west coast of Mexico, but all the action has been in the Atlantic this year. This is a common phenomenon where if one basin is very active, the opposite basin is usually dominated by sinking air that hinders tropical development” Howlett said.

Last year’s monsoon was a bust in Tucson, which normally would receive 6.08 inches of rain from mid-June through September. That monsoon, at 5.06 inches, was more than an inch short of normal. But this year’s monsoon is even worse: With only 1.62 inches through Sept. 19, the current season could come close to rivaling the driest monsoon on record. That was 1924, when Tucson only recorded 1.59 inches.

“And then we’re looking at La Niña conditions likely continuing through winter, which will have a compounding effect on drought conditions, since historically that means dry weather across the southwest,” Howlett said.

Although La Niña years aren’t always dry — weak La Niña years in 2001 and 2017 brought above-average rainfall to downtown Los Angeles — a La Niña appears to be building in the tropical Pacific, and they’re often a dry precursor for Southern California, Patzert agrees.

If La Niña conditions lead to a dry winter, clearly the Santa Anas will win the annual race of the elements that Patzert described, with winter rains providing only paltry relief.

Geography and weather systems contribute to the strong offshore Santa Anas

“We have to be super-duper cautious about the fire danger because the situation is incendiary,” said Patzert. “We’ve written this story too many times over the last couple of decades,” he warns. “It’s time we implement the lessons we’ve learned.”

As the climate heats up and dries out, those lessons include, according to Patzert, how we manage forests and zone fire-prone communities. Also, we need to examine what kinds of building codes are required in the urban-wildland interface.

He finds our current approach to dealing with urban growth with increasingly explosive fire conditions “unsustainable and unaffordable — too dangerous and too costly.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.