Column: Trump inspired them to become U.S. citizens and to vote. Against him

For the past 20 years, the Serranos of Lakewood have kept a family pact based on equal parts patriotism and vengeance:

Become an American citizen. Register to vote. And go with the Democrats to stick it to the Republicans.

Rafael and Carmela Serrano came to Southern California in 1991 from Guadalajara, Mexico, with six of their eight children after their general store went under. They had wonderful memories of the Southland from visits to Disneyland, and figured life here would be peaceful and welcoming.

It wasn’t.

California was about to embark on a decade of legislative xenophobia led by the GOP. First came Proposition 187, the landmark 1994 ballot initiative that sought to make life miserable for undocumented immigrants. Similar laws spread in cities across the state that decade and eventually metastasized into a national anti-immigrant movement that helped plop Donald J. Trump in the White House in the 2016 election.

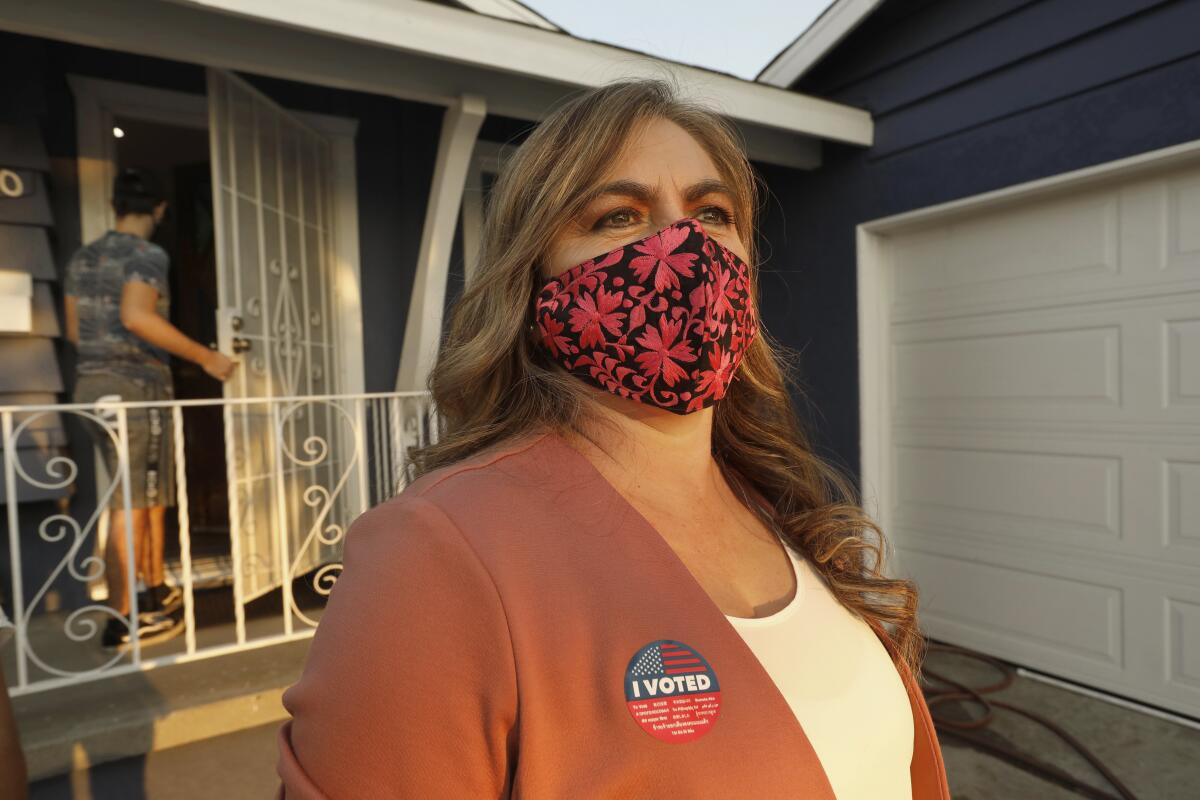

“We all came to come ahead, not to take away anyone’s bread,” said Gabby Serrano, 46, as she stood in front of her parent’s well-kept tract home. Three of her siblings — Francisco, Juan, and Teresa — nodded in agreement. Signs for Congresswoman Linda Sanchez and Assemblyman Anthony Rendón decorated the lawn. Teresa wore an “I Voted” sticker, while Juan’s son held mail-in ballots other family members had yet to turn in. “To see such anti-Mexican hate was just hurtful.”

“Our eyes were quickly opened,” added 42-year-old Francisco. He remembered walkouts at Artesia High School against 187 that he and his brother didn’t participate in for fear that immigration agents might take them away.

“We couldn’t vote back then, because we weren’t citizens,” responded Juan, a 44-year-old supervisor for Hawaiian Garden’s community services department. “But I remember being a teen, and promising that as soon as I could, I’d register as a Democrat.”

He was the first Serrano to become an American citizen, in 2000. Other siblings followed. And then they waited for their parents to do the same.

And kept waiting.

Rafael, 73, and 70-year-old Carmela didn’t seem to be in a hurry. Life in el Norte had been just fine as permanent residents. They thought taking the citizenship test in English would be too hard.

Then came Trump.

In March, the married couple of 53 years took their citizenship oath and immediately registered to vote. Last week, they dropped off their ballots at a voting drop box in Hawaiian Gardens before embarking on a long-planned vacation to Guadalajara. Juan filmed the occasion, then put it up on the Serranos’ TikTok channel with “This is America” by Childish Gambino as a soundtrack.

They voted for Joe Biden, of course.

And they’re not the only first-time Latino voters expected to do the same.

Juan Serrano said that he’s spoken to scores of Hawaiian Gardens residents who registered to vote specifically to get Trump out of office. He compared the president’s inadvertent inspiration for these first-timers to his own experience with Pete Wilson, the California governor who championed Proposition 187 and arguably led an entire generation of Latinos in the state to turn blue.

“Pete Wilson was my idol. He was my hero,” said Juan sarcastically, but with gratitude. “Thanks to him, we were going to vote. We grew up with that injustice.”

“It’s like the J-Lo film,” Gabby added. “Enough is enough.”

::

The Serranos are what small-town Mexicans like my family call gente decente — literally, “decent people,” but really signifying humble folks who don’t like to draw attention to themselves and are exemplars of community life.

For 25 years, the Republican Party has alienated gente decente. And if the Serranos are any indication, this is the year that these people will get their revenge.

In this election, Latinos represent the largest minority voter bloc — 32 million strong — for the first time.

The only thing that can save the GOP and Trump from a historical shellacking is, well, history.

Only three times in the last 40 years of presidential elections has the Latino voter turnout rate exceeded 50%. In the 2016 election, according to Pew Research Center estimates, 65.3% of eligible white voters did so, while Black voters did the same at 59.6%. Latinos? Only 47.6%.

This embarrassing figure leads to bad clichés about how Latinos are the “sleeping giant” of the American electorate and have yet to “flex their political muscle.”

Latinos should be ashamed for their apathy, according to the Serranos.

“If you don’t vote, it’s like not using your voice,” said Teresa.

“It’s frustrating,” said Gabby, the last Serrano sibling in the United States who hasn’t become an American citizen. She then looked at her 26-year-old daughter, Ana Ascencio. Though she was born here, Ascencio had never voted in her life.

“I would always scold her, ‘Vote!’” Gabby said. “You don’t know when the government can deport people like me. And If I’m gone, who’s going to take care of you and your sister?”

I asked Ana why she hadn’t voted before.

“I don’t know,” she responded.

“Por floja,” Juan cracked. Laziness.

But Trump changed her perspective, just like her grandparents.

“It’s my time now,” she said.

Now Juan smiled.

“My dad always loves to talk politics,” he said. “And he hates Trump. He’s from a different generation. You can’t have falta de respeto [lack of respect] for people. And that’s what Trump has against Mexicans.”

“My grandpa came as a bracero to Bakersfield,” Gabby said. “And he’d always say about the United States that those who take advantage of the opportunities and didn’t do anything bad could get ahead. But Trump’s only done bad. My parents get angry at what he has done to this country.”

While the Serrano kids were kind and funny, I wanted to talk to their parents. So Juan dialed up Rafael and Carmela on FaceTime. The two sat at a plastic-wrapped kitchen table in their Guadalajara home and beamed. They reminded me of my aunts and uncles — soft-spoken, of few words. Gente decente.

How did they feel about voting for the first time?

“Happy, content, and proud,” Rafael said.

“Our hearts fill up for being able to participate,” Carmela responded.

What’s so bad about Trump?

“He talks a bunch of things that doesn’t sit well with you,” Rafael said. “This man sows division.”

“The U.S. is a strong country,” Carmela said. “A president that’s just is the best.”

What did they want other Latinos to learn from their example?

“May we serve as motivation for other people that sí se puede,” Rafael said.

I thanked them for their time, and they did the same. Then Carmela, like any modern-day decent person, had one last thought.

“Gracias, and follow us on TikTok!”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.