Settlement aims to improve ‘insufficient’ conditions at L.A.County’s juvenile halls

- Share via

State investigators announced an agreement Wednesday with Los Angeles County to improve conditions in its troubled juvenile detention centers — the result of a two-year investigation that found the lockups had insufficient services and endangered youth safety.

California Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra said the settlement, which creates a four-year plan to improve conditions in the halls and camps, seeks to limit the use of force, create a more homelike setting for the youths and boost their educational and mental health services, among other reforms.

The settlement came amid the prospect of potential civil action in Los Angeles County Superior Court by Becerra’s office — litigation that county lawyers said Wednesday they were loath to defend.

Becerra, joined in an online news conference with Hilda Solis, who chairs the county’s Board of Supervisors, said the agreement is the result of more than 80 interviews and a review of thousands of documents. He said the findings center on the unnecessary use of oleoresin capsicum spray, commonly known as pepper spray, and unreasonable periods of cell confinement that prevented youths from receiving adequate educational and medical care.

“In the end, we found that the county of Los Angeles had been providing insufficient services to its youth and failed to protect from risks to their physical safely, including the uses of excessive force by facility staff,” he said. “This two-year investigation was for the purpose of getting us to move in the right direction.”

The probe found that, in some cases, youths were mistreated and dehumanized. Becerra said he believed the deal would help the department continue trying to focus on improving the conditions and environment for the youths in the facilities.

“We have hope for all of our kids, and we want them to believe in themselves and that they can trust that we believe in them,” Becerra said.

L.A. County juvenile halls are so chaotic, officers are afraid to go to work

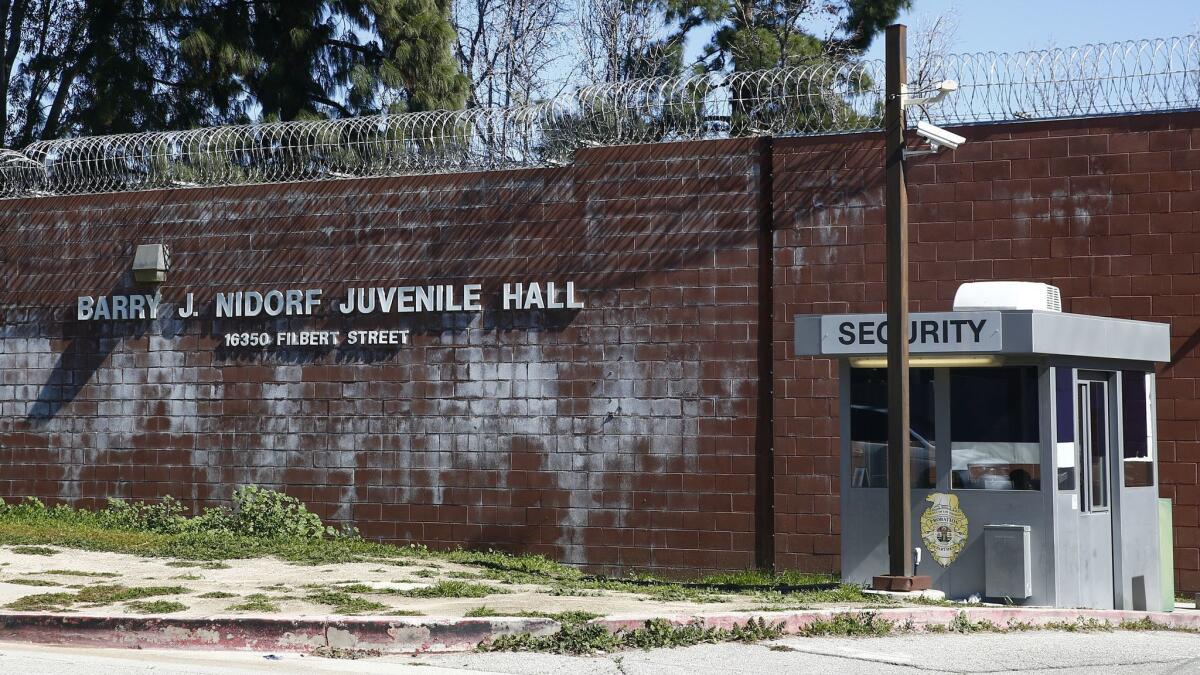

The existence of the California Department of Justice investigation was revealed after The Times reported in May 2019 on “chaos” inside the Barry J. Nidorf Juvenile Hall in Sylmar.

The Times article described an incident that left a unit in the facility with shattered windows, smashed walls and tiles ripped from the ceilings. Phones in common areas had been broken, debris was scattered on the floors, and gang graffiti had been scrawled on the walls.

Staff members said they felt overwhelmed.

The incident followed months of scrutiny at the halls about the use of pepper spray on youths inside the Los Angeles County Probation Department’s juvenile halls.

A review by the county Office of Inspector General found that the Probation Department has inadequate training, supervision and accountability systems that contribute to an over-reliance on the pepper spray, which is designed to cause severe irritation in the eyes and skin to control unruly subjects.

Though the department oversees tens of thousands of adult probationers, with 6,000 employees and a $1-billion budget, the thrust of the current reform effort is focused on juvenile detention facilities. Its officials didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

Its juvenile halls and camps house roughly 300 youths either awaiting disposition in courts or carrying out court-assigned rehabilitation.

The number has steadily declined in recent years amid the pandemic and efforts generally to send more youths to community treatment and home environments.

The juvenile operation — among the nation’s largest — has been under scrutiny for years amid reports of excessive pepper spray use by detention officers, as well as reports of increasing youth violence and the plummeting of staff morale.

The county has already endured an investigation into the use of pepper spray, which is being phased out, by its own Office of Inspector General’s extensive report. The county in 2018 also formed the Probation Reform and Implementation Team, which spent more than a year taking testimony and synthesizing past recommendations into an action plan in 2019.

Still, problems persist.

Emilio Zapién, a spokesman for the Youth Justice Coalition, a reform group, said the announcement was an “important step in the right direction” but urged the department to continue reducing the incarcerated population and closing facilities.

The group has advocated a ban on physical or chemical force, such as pepper spray, and solitary confinement. In addition, the group has urged the Board of Supervisors to remove youth offenders from the larger probation department and into one focused solely on their development.

“We’ve been asking for these changes for a long time, and they still haven’t implemented them. It took a state investigation to get these reforms on paper,” he said.

Solis, who has been outspoken on juvenile hall conditions in the past, said the reform plan highlighted in the settlement fits with the county’s broader effort to move away from excessive incarceration in favor of treatment. She noted that the population inside the juvenile halls had declined dramatically in recent years, from roughly 900 two years ago to about 300 today.

“This settlement is another important element, in my mind, in the extensive juvenile justice reforms that have been coming our way here at the county,” she said. “It’s putting care first — jail last. That’s our motto now.”

Asked about the uneasy implementation or failure of past reforms at the troubled operation, Becerra said the settlement had teeth — given the prospect of court action — and that it would be overseen by a monitor.

“There has to be real follow-through,” said Becerra, who has been named to run the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services by President-elect Joe Biden. “If there isn’t implementation the way that there should be, the monitor will be on top of that, and if we need to push harder, we can always go to court.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.