Column: What do conductor Gustavo Dudamel and rocker John Densmore have in common? Plenty

- Share via

You need a break, right?

I know I do. We’re cooped up and locked down, and when we turn on the TV news, it’s politics and the pandemic all the time, nonstop.

So here’s something a little different, and I offer it up as a short vacation from your cares and woes. It’s about two stars from different constellations who met here in Los Angeles, crossroads of artistic invention, and struck up a bond.

John Densmore, who grew up in L.A. and played drums for the Doors, has a new book out called “The Seekers.” It’s a collection of stories and musings about Densmore’s musical heroes, people who sought and found truth and reason in art, and also found what the drummer calls “the thread that tugs on our humanity.”

Densmore writes about his own experiences and those of other musicians he’s known, including Patti Smith, Jim Morrison, Lou Reed, Janis Joplin, Van Morrison, John Coltrane drummer Elvin Jones, and one of my favorite local artists — jazz, blues and soul singer Barbara Morrison — among others.

Two of my favorite chapters are on Densmore’s mother, Mary Margaret Walsh, “who loved music so much” she let him set up his drums in the living room, and Robert Armour, the Daniel Webster Junior High music teacher who persuaded Densmore, a pianist at the time, to play drums in the school band.

And then, in Chapter 21, we get the maestro.

Los Angeles Philharmonic conductor Gustavo Dudamel.

I’ve known Densmore since 2009, when I wrote about him sponsoring the refurbishing of a revered Highland Park mural that had been damaged. Over the years I’ve heard Densmore, who famously refused to allow Doors music to be used in a car commercial, talk about his love of jazz and classical music, and I vaguely recalled that he had written for the L.A. Times a decade ago about being star-struck by Dudamel.

In “The Seekers,” Densmore reprised and updated his L.A. Times story about Dudamel, and he gave Chapter 21 the same title as his L.A. Times piece: “The Rocker and the Dude.”

When I read the chapter, I thought it would be pretty cool if I could get together with Densmore and Dudamel and talk to them about Los Angeles, about music, and about the kinship they’ve found. We’ve just come through four years marked by division, and here’s a curious and uplifting union, built on the healing power of music.

Dudamel, a child of Venezuela, is just shy of 40; Densmore, who attended Cal State Northridge before it was called that, will be 80 in a few years. One breathes the music of the gods; the other plays what’s been called the devil’s music.

But as Densmore told Dudamel in an early meeting, after hearing the L.A. Phil play Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique, “I played timpani on the Berlioz piece in high school,” and as Dudamel told him, “Juan, Mahler is heavy metal, si?” Both the rocker and the dude share a love of Los Angeles and a faith in nurturing young souls through music.

Thanks to the coronavirus, we couldn’t get together. But I did ring Densmore and then called Dudamel, who was in Madrid with his wife, Spanish actress Maria Valverde.

Densmore, who has been attending L.A. Phil concerts since the orchestra’s home was on Pershing Square, recalled seeing Dudamel perform as guest conductor in 2007, two years before he took over the baton from conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen.

“I just couldn’t believe it,” said Densmore, who was transfixed by the spectacle of Dudamel, whose energy and long curly locks reminded him of the lead singer in Led Zeppelin, and whose energy evoked Bob Marley. “Everything he was doing with his body was an elaboration of what you were hearing. Wow!”

Densmore worked his way backstage, waited in line, then introduced himself as Jim Morrison’s drummer. Densmore says Dudamel took his hand and bowed, his hair washing over Densmore’s wrist.

That sounds like a gracious move by Dudamel, but was he really familiar with the Doors, whose music was hot a decade before he was born?

“Of course,” Dudamel told me, saying that any musician can appreciate what was such a distinctive sound. “I loved the Doors.”

Dudamel said he had a grade school assignment to translate a song from English into Spanish. An older cousin, a big fan of American rock, had introduced him to the music of Pink Floyd and Led Zeppelin, but Dudamel chose a Doors song for his translation.

Which song?

“Touch Me.”

And in case I wasn’t familiar with it, Dudamel began to sing. It was just a few words, but I’m not sure anything in the rest of my career can top this — one of the classical world’s brightest stars seated at a piano and singing a 1969 rock ‘n’ roll hit to me on a Zoom call from Spain.

“Come on, come on, come on, come on touch me, babe,” Dudamel sang.

So what did his teacher think about him translating such provocative lyrics?

“She loved it,” Dudamel said. “It was the most romantic song.”

Upon meeting Densmore decades later, Dudamel said, “the connection was immediate, like you saw a brother.”

Densmore felt that Los Angeles could not have found a better fit, given Dudamel’s talent and the potential for drawing a younger, more diverse audience into classical music in a region half Latino. He knew, too, that Dudamel had come up in Venezuela’s El Sistema, the music training and human development program for children. Dudamel once said of the program, “Music saved my life and has saved the lives of thousands of at-risk children in Venezuela.”

In Los Angeles, Dudamel was an early champion of the Youth Orchestra of Los Angeles, which was based on El Sistema, and one of the first big donors was guess who.

“John is a part of the family,” Dudamel told me.

Densmore once flew to Oakland for a YOLA concert, with Dudamel conducting, and told me he always gets inspired seeing a diverse group of kids from Los Angeles play music written hundreds of years ago, by white Europeans, as if they’d written it themselves.

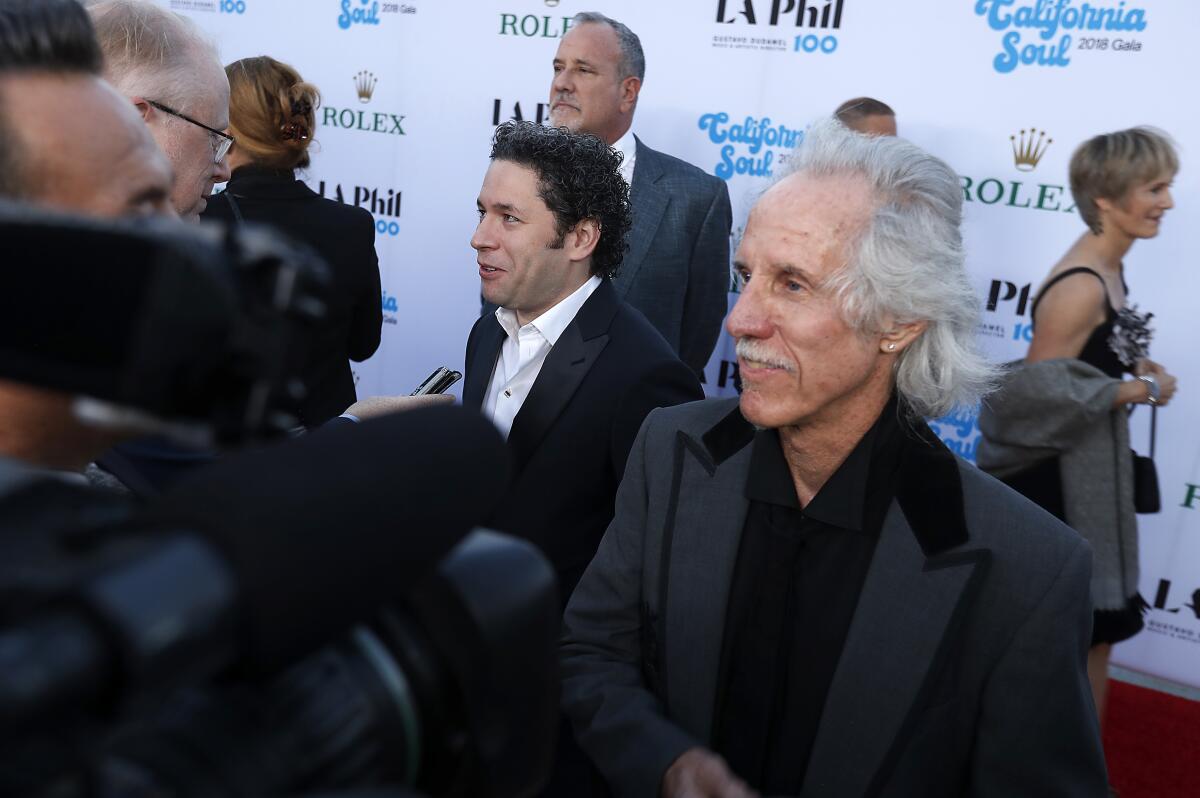

In 2018, the L.A. Phil was putting together a 100th anniversary program celebrating “California Soul,” as the concert was called. It featured music by Frank Zappa, the Beach Boys, Jerry Goldsmith’s “Love Theme” from “Chinatown,” and, among other works, one piece by a band of note.

“Gustavo called and asked me if I would do ‘L.A. Woman’ with the orchestra,” Densmore said of the 1971 Doors hit.

“Oh,” thought Densmore, “I’m going to be playing with the L.A. Phil — 85 of the world’s greatest musicians.”

Dudamel stood, baton raised, with Coldplay’s Chris Martin standing in for Jim Morrison. Densmore was perched on an elevated stage behind the orchestra, painted by the spotlight. The timekeeper began the piece, kept the motor running, and ended the song with flair, rising to slam the cymbals as the Disney Hall audience cheered.

Dudamel said he hopes there will be another chance to collaborate with Densmore, and he hopes it won’t be much longer before live performances resume. Music is reflection, he said, and we’re living in times that call for deep reflection.

The maestro said he loves that there is no one type of music in Los Angeles — it’s as varied as the people themselves. He feeds on that creative energy, whether it’s “hip hop … or salsa or mariachi or rock.… We see this as a symbol and an opportunity to send a message of unity.

“People try to build borders and divide us,” he said. “We try to build bridges.”

steve.lopez@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.