Latino COVID-19 deaths hit ‘horrifying’ levels, up 1,000% since November in L.A. County

The COVID-19 death toll among Los Angeles County Latinos is reaching frightening levels that the county’s top health officials have called “frankly horrifying,” prompting new calls for the government to do more to help essential workers and people living in dense, overcrowded conditions.

The illness has long hit Latinos in disproportionate ways. Poor Latino neighborhoods are highly susceptible to the spread of the coronavirus because of dense housing, crowded living conditions and a higher proportion of essential workers who are unable to work from home. Officials think people get sick on the job and then spread the virus to family members at home.

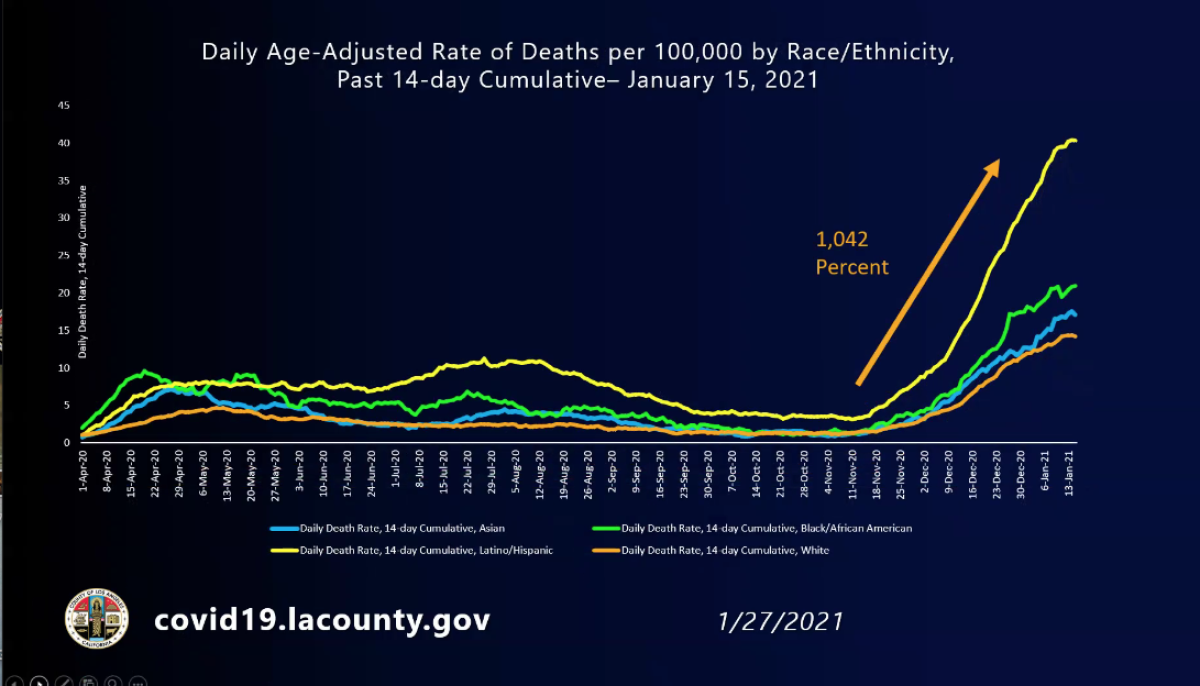

When the latest surge began in November, the number of Latino residents in L.A. County who were dying from COVID-19 daily — on average, over a two-week period — was 3½ per 100,000 Latino residents.

The latest data show how that number has skyrocketed: 40 deaths per 100,000 Latino residents.

“That’s an increase of over 1,000%,” L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said this week. “Our Latinx community is, in fact, bearing the worst of this pandemic.”

Los Angeles City Council President Nury Martinez said the government should bring help to L.A.’s hardest-hit communities as fast as possible.

“Some of those folks do not have time to waste. It can mean life or death for them,” Martinez said at a news conference earlier this month as Dodger Stadium became the site of a giant vaccination center. “We need to ensure that we are addressing the hardest-hit communities. ... This is about creating access, particularly in communities of color. We need to create access in these neighborhoods.”

Martinez said inequity can no longer be ignored. Getting vaccines to essential workers is paramount, as they have been risking their lives to keep society running, she said.

Many essential workers — cashiers, truck drivers, meat packers — are Latino. They can’t stay home. And they’re being hit hard by the novel coronavirus.

“If we don’t focus on equity now, I’ll tell you who is going to get the vaccine: It’ll be the people who have the luxury to stay at home and send their children to open private schools and neighborhood learning pods,” Martinez said. “And the people who will not get the vaccine will be the nannies, the maids, the housekeepers and the gardeners, the people who take our groceries, who prepare our food every day, who deliver our mail and clean our streets.”

This week, L.A. County Supervisor Holly Mitchell voiced concern about restaurants being reopened for outdoor dining on Friday even as restaurant workers under the age of 65 are not yet eligible for vaccinations.

“We’ve got to figure out how to target those who are truly at most risk,” Mitchell said.

The COVID-19 death rate has also jumped dramatically for Black residents. The toll in early November soared from 1 death a day per 100,000 Black residents to more than 15 deaths a day per 100,000 Black residents by Jan. 6. And the latest data show that figure is now 20 deaths per day, on average, per 100,000 Black residents.

Deaths also have increased “dramatically” among Asian residents, Ferrer said. The rate grew from 1 to 12 daily deaths per 100,000 Asian Americans between early November and Jan. 6; the latest data show there are now 17 deaths per 100,000 Asian residents in L.A. County.

White residents’ daily death rates had increased from 1 in early November to 10 per 100,000 white residents as of Jan. 6; it’s now 14 deaths per 100,000 white residents, on average.

Among all groups, the COVID-19 death rate for Latino residents in L.A. County is nearly triple that of white residents.

“While every single race and ethnicity group in L.A. County has seen a horrendous increase in mortality rates, the gap between the experiences of those in our Latinx community and all others is frankly horrifying,” Ferrer said.

California’s Latino and Black residents and people with no more than a high school degree suffered among the highest increase in deaths during the pandemic, according to an analysis by researchers at UC San Francisco.

California counties with a greater share of low-wage and crowded households have been hit harder by the pandemic, according to a study by the UC Merced Community and Labor Center. And Latino workers have the highest rate of employment in essential front-line jobs, where there’s a higher risk of exposure to the coronavirus, according to the UC Berkeley Labor Center.

For instance, 55% of Latinos work in such jobs, and 48% of Black residents do, compared with 35% of white residents.

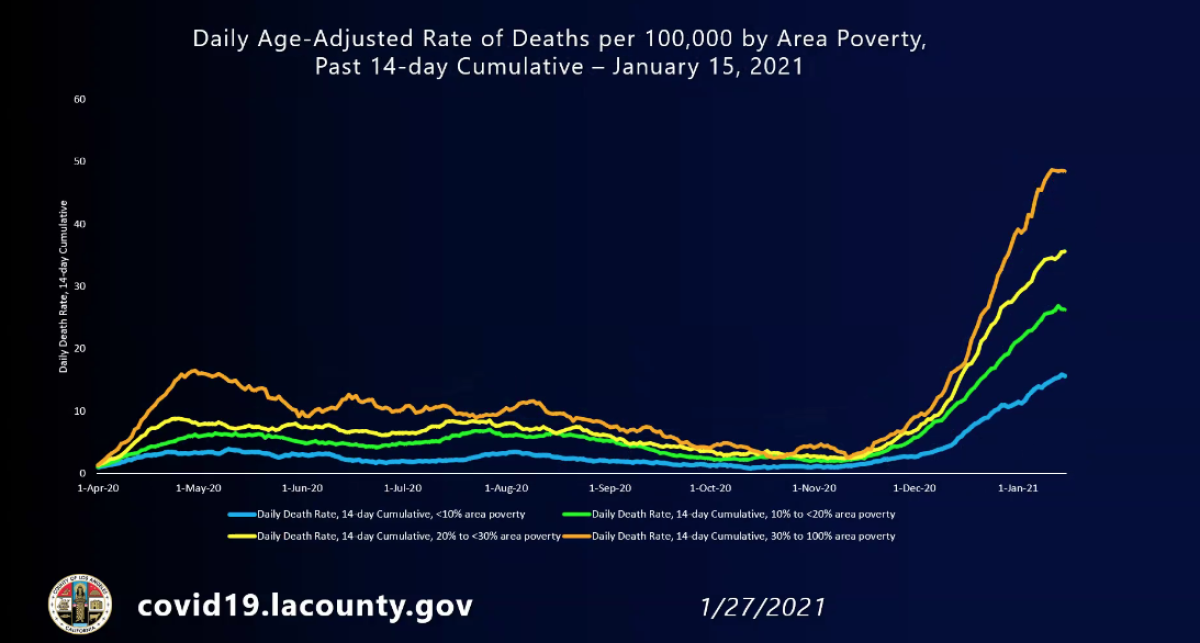

The latest surge has also caused a far higher rate of COVID-19 deaths among residents of L.A. County’s poorest neighborhoods compared with those living in wealthy neighborhoods.

In early November, the COVID-19 death rate among all income groups was fairly even: about 2 to 3 deaths per 100,000 residents, Ferrer said. While the death toll among people in the wealthiest neighborhoods climbed to 15 deaths per 100,000 residents, the impact was three times worse among those in the poorest neighborhoods — 48 deaths per 100,000 residents.

Elected officials in L.A. County, where roughly 75% of residents are nonwhite, are increasingly voicing deep concern about the disparities and are urging more action to bring greater help to vulnerable communities whose members are disproportionately dying.

That includes improving access to vaccines in the hardest-hit areas, and working to establish greater trust in communities that are disproportionately hesitant to get the vaccines, officials say.

Amid concerns that there’s a significantly lower rate of COVID-19 vaccinations for healthcare workers who live in South L.A. — home to large populations of Black and Latino residents — L.A. County officials arranged for the opening of six vaccination sites there, including at the outpatient center at Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital, St. John’s Well Child & Family Center and three Rite Aid pharmacies.

Mayor Eric Garcetti says he’s confident manufacturers will meet demand and additional COVID vaccines will be approved. But many more doses are needed.

Populations currently granted access to the vaccines include healthcare workers, residents of nursing homes and other long-term care facilities, and seniors 65 and older. The next group to be given access to vaccines will be people working in education and child care; food and agriculture, which includes restaurant workers; and public safety. But it’s unclear when those people will actually get access to the vaccines.

A shortage of shots continues to be a huge problem around the country.

Over 2 million of L.A. County’s more than 10 million residents are eligible to receive the vaccine. But with each person who receives the Pfizer or Moderna vaccine needing two doses, L.A. County has not received enough to fully vaccinate those who are eligible.

According to data disclosed Friday, more than 719,000 doses of vaccine have been administered in L.A. County — about 595,000 first doses and about 124,000 second doses.

“This is still below where we would like to be. But we continue to be challenged by a limited supply of vaccine,” said Dr. Paul Simon, chief science officer for the L.A. County Department of Public Health. “While we are hopeful there will be an increase in supply of vaccine in the coming weeks, there are no guarantees. We are currently receiving approximately 150,000 vaccine doses per week.”

L.A. City Councilman Marqueece Harris-Dawson, who represents South L.A., expressed concerns about the initial government strategy of routing vaccines to large sites like the Forum in Inglewood. He said his constituents are “not going to any place with big crowds of people,” and also criticized the demographic makeup of those receiving shots at the Forum as not representative of the neighboring community.

Ferrer said she agreed that it’s important to route vaccines to smaller healthcare providers with a trusted reputation in communities. “It’s so much easier to go to somebody you trust,” she said.

She said Wednesday that the next two weeks will probably continue to be rocky but hoped that vaccine shipments would be more predictable in the near future.

Also on the horizon is the potential approval of a third vaccine, manufactured by Johnson & Johnson, that requires only one dose and is less expensive to produce.

“Once we start getting the third vaccine here, that automatically will increase the supply,” Ferrer said.

Times staff writer Dakota Smith contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.