Ethical land mines, ‘Sophie’s Choice’ moments as California decides who gets COVID-19 vaccine next

- Share via

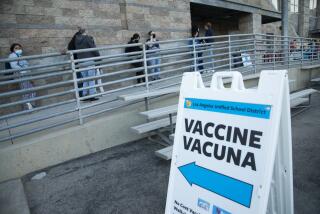

With COVID-19 vaccine doses still in short supply, the decision of how to prioritize immunizations is becoming an increasingly fraught matter as officials must choose among many groups, each with its own desperate need to get to the front of the line.

Focusing on older people, the disabled and others at higher risk of becoming critically ill from the coronavirus has the potential to save many lives. Reserving doses for essential workers would also help slow the spread of COVID-19. And moving educators to a higher position could make teachers willing to return to campus for in-person instruction.

“What’s so difficult right now is that we even have to view this as competing priorities. There’s all this tension on shifting priorities in groups, and all of this is based on a limited supply,” said Dr. Eve Glazier, president of the Faculty Practice Group at UCLA Health. “There’s a lot of different lenses to look at it.”

So far, a number of California‘s most populous counties have generally prioritized healthcare workers, those living in long-term care settings and people 65 and older for vaccinations. The state is getting only a fraction of the vaccine it needs, so it will probably take weeks or months to get through those groups.

But there has been much debate about who goes next, with labor unions, disability rights groups, teachers and others all making their case. The state’s 60-member vaccine advisory committee has spent weeks discussing the matter.

During an advisory meeting Wednesday night, members from the smaller group responsible for drafting the state’s vaccine guidelines said that new recommendations would be presented to the state following meetings Friday among the working group and a new state task force.

The state task force, composed of members from the departments of Aging, Disability Services and Health and Human Services, was recently launched to sort out the logistics for how residents with disabilities and underlying health conditions could be prioritized next.

“We are taking this incredibly seriously. This is the next priority group,” state epidemiologist Dr. Erica Pan said during a committee meeting on Wednesday.

The committee’s current proposal is for individuals ages 16 to 64 with underlying health conditions or disabilities to be the next eligible group in the vaccine rollout.

It was not immediately clear whether the recommendations would usurp previous plans to target an age-based priority list or how eligibility would be determined. It also was unclear when vaccinations would become available for those groups.

Teachers and child-care workers and those who work in food, agriculture and emergency services are already slated for priority after healthcare workers, long-term care facility staff and residents and adults 65 and older. But limited vaccine supplies has made it unclear how quickly they will get to the front of the line.

There is growing belief that mass vaccination can finally turn the tide of the pandemic this year. Officials hope the supplies will increase, but until then they are forced to make the tough calls.

“There are lots of people who need to get vaccinated, and it’s very hard to determine which of these priorities is more urgent, pressing and important,” said Los Angeles County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer. “So we all are going to need to be patient.”

Among the groups to consider are people whose age, underlying health conditions or other circumstances put them at greater risk of dying from COVID-19. Other Angelenos work in settings with a heightened risk of coronavirus transmission and could potentially carry the virus home with them. Others are employed in fields that provide critical public services.

In L.A. County, 193,950 doses arrived the week of Jan. 11, but only 168,575 were delivered the following week and 146,225 the week after that.

“The name of the game right now is to keep everyone alive,” Ferrer said. “That’s the No. 1 priority for us ... to get as many people as we can to be able to stay alive during this pandemic, and to reduce the risk for those who are at highest risk of dying.”

State guidelines provide local officials with some discretion over who else to prioritize — and these options include teachers. As a result, some local health agencies have begun to accept appointments to vaccinate teachers and other front-line educators, including Riverside County and Long Beach — which has its own local public health department independent from L.A. County — while others have not.

But simply allowing teachers to get in line with everyone else isn’t necessarily going to result in schools reopening faster — if teachers have the same problems scheduling appointments as everyone else. And are the educators who are able to get appointments the ones most needed to get campuses up and running for the students with the highest needs?

As for teachers, state and federal officials have insisted for some time that campuses for kindergarten through 12th-grade students can reopen safely without teachers being vaccinated. But teachers in some areas, including Los Angeles, say the only safe approach is full vaccination before schools reopen.

In addition to seniors, Riverside County and Long Beach have opened up vaccination appointments to those working in education and child care, food and agriculture and emergency services.

San Bernardino County has opened up vaccinations to first responders such as firefighters and police officers, but not educators or food workers.

But in opening up vaccinations to more groups, there are questions whether that’ll make it more difficult for seniors — who are far more likely to die of COVID-19 — to get their shots. In L.A. County, about 70% of those who have died from COVID-19 were age 65 or older.

A statewide shortage is so acute that some counties in California that had begun to offer vaccines to lower-priority groups, such as teachers, child-care workers and others who work in educational settings, have stopped vaccinating that group in order to focus on seniors.

Marin County on Jan. 21 announced that supply limitations had forced it to prioritize vaccinations on those 75 and older, and officials stopped scheduling appointments for people in lower-priority groups.

A joint statement by eight local health agencies in the Bay Area on Wednesday said that officials will prioritize healthcare workers, people living in long-term care settings and seniors. Marin, Napa, Santa Cruz and Solano counties are prioritizing residents 75 and older; while Contra Costa, San Francisco, San Mateo and Santa Clara counties are prioritizing people 65 and older.

The Bay Area doesn’t have enough vaccines to inoculate all residents 65 and older, much less educators, food and agricultural workers and first responders, the officials said.

“We need to be direct and honest with the public that, although we want to vaccinate everyone, right now, we just don’t have enough vaccine to do so,” Dr. Sara Cody, the health officer and public health director of Santa Clara County, said in a statement. “Given the limited supply of vaccine, we must prioritize vaccinating those at greatest risk of death or serious illness.”

Besides healthcare workers and long-term care residents, Ventura, Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo counties are focusing on seniors age 75 and over; L.A., San Diego, Orange, Kern and Imperial counties are focusing on seniors age 65 and over. Pasadena, which runs its own public health department, is following the same focus as the L.A. County Department of Public Health.

Medical experts said the discussion of prioritization is filled with ethical land mines.

“We need to recognize there’s a real danger there — even if only at the symbolic level — of attributing social value to certain people or certain groups,” said Dr. Aaron Kheriaty, director of medical ethics at UC Irvine.

Kheriaty says that an age-based approach, starting with most elderly, is ethically justifiable, but the question of who should receive the vaccine next remains a complex and ever-changing strategy.

But others also make convincing arguments.

“I’m working eight-hour shifts indoors, exposed to like a thousand people a day,” a 31-year-old grocery store worker from Santa Cruz said.

The worker, who asked to remain anonymous, added that the ongoing confusion over who gets priority is one more frustration in a year in which supermarkets and other retailers that remained open during the pandemic have seen COVID-19 outbreaks.

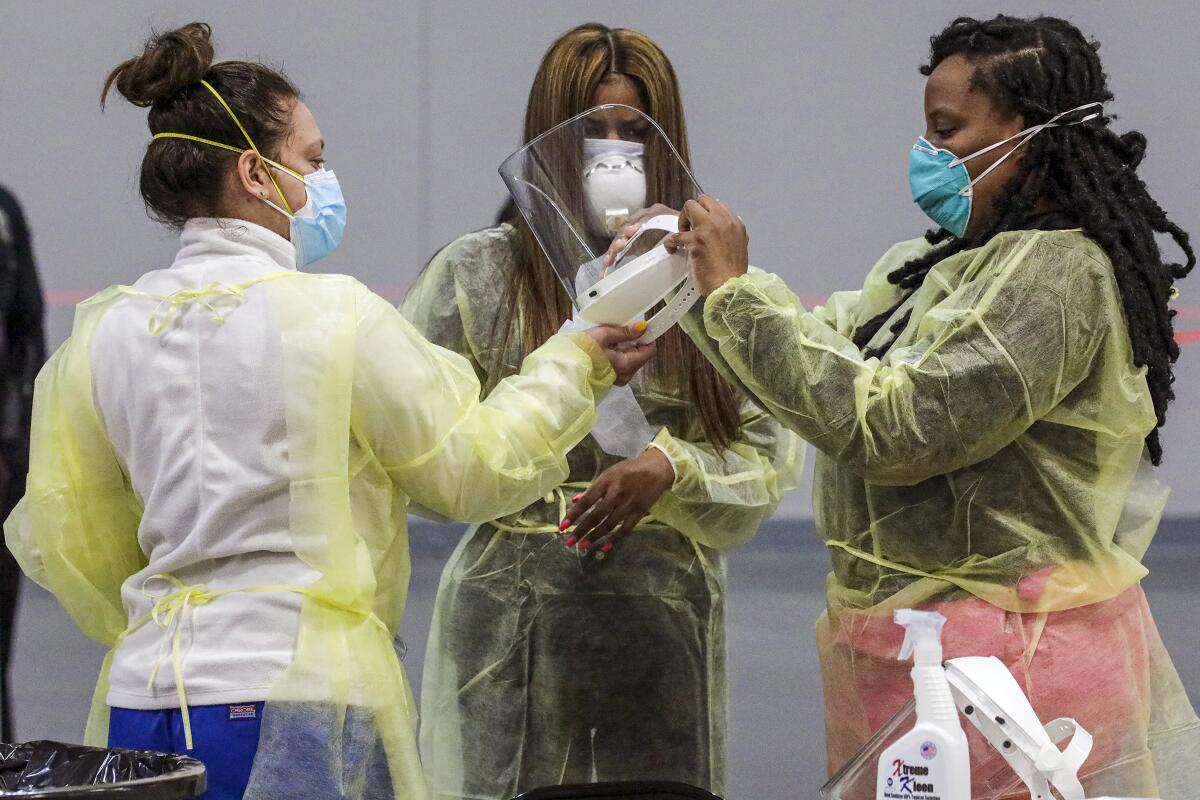

Exposure has been a key argument for the vaccine among many who work as essential workers on the front lines, serving customers face-to-face without ability to work from home. In early talks of vaccine rollout strategy, essential workers were given greater priority. But over time, the plan shifted.

“I understand the idea of prioritizing people based on exposure. But at the public policy level — and given the impacts on society — I think it starts with people most at risk of bad outcomes and moves down the line from there,” Kheriaty said.

Advocates for the disabled have been fighting to make sure that group gets a higher priority.

“I will feel a lot better when state officials commit to a time frame for vaccinating high-risk people with disabilities,” Andy Imparato, executive director for Disability Rights California and a member of the vaccine advisory committee, said Wednesday. “It feels like we are getting lip service,” he said about the lack of concrete information that accompanied news about potential new priority guidance.

Dr. Paul Offit, a professor of vaccinology at the University of Pennsylvania, said last month during a panel discussion at UC San Francisco that coming up with a vaccination priority plan is tough.

“This is hard. I mean, this is like the Sophie’s Choice, right? I mean, do you want to vaccinate people who are at highest risk? Do you want to vaccinate people who help the society move along?” Offit asked. Unfortunately, there could be another 100,000 or 200,000 people who will die of COVID-19 nationally over the next couple of months — whose lives could’ve been saved by the vaccine — but simply hadn’t been able to get it, he said.

“It’s really hard. You only have so many lifeboats there that enable you to save people. And it just breaks your heart,” Offit said. “So get it out there — get the vaccine out there as much as you can. Realize that you’re going to be really upsetting one group or another. ... You’re going to anger people anyway. So just do what you think works best.”

Times staff writer Howard Blume contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.