It would be arguably the most ambitious public works project in San Diego history.

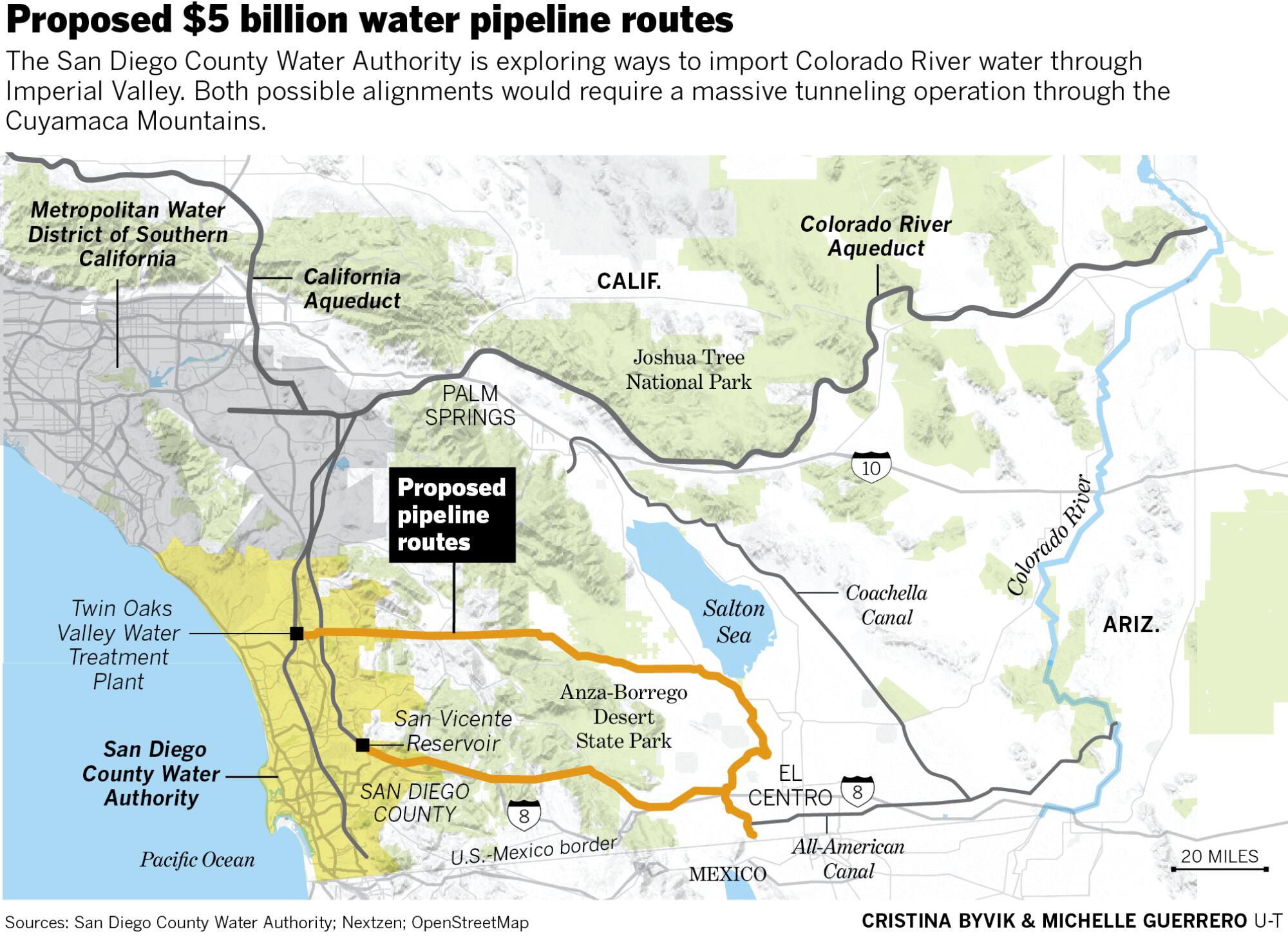

The envisioned pipeline would carry Colorado River water more than 130 miles from the Imperial Valley — through the Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, tunneling under the Cuyamaca Mountains, and passing through the Cleveland National Forest — to eventually connect with a water-treatment plant in San Marcos.

An alternative route would run through the desert to the south, boring under Mt. Laguna before emptying into the San Vicente Reservoir in Lakeside.

Estimated cost: roughly $5 billion. New water delivered: None.

Proponents of the modestly named Regional Conveyance System say the project has the potential to save ratepayers billions of dollars by the end of the century.

The region has long received most of its water through a series of pipes and canals to the north via the Los Angeles-based Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, or MWD. The new pipeline would connect San Diego directly to the Imperial Irrigation District, or IID, and its All-American Canal outside of El Centro.

Those pushing the project argue that MWD has long overcharged San Diego for delivering water, including supplies the region has purchased from IID.

“If there’s a way to bring water to our region cheaper and more efficient, we owe it to our ratepayers to do our due diligence. It’s that simple,” said Jim Madaffer, who as a board member of the San Diego County Water Authority has worked tirelessly over the last two years to advance the venture.

The idea of building a new pipeline to Imperial Valley just to bypass MWD has enraged environmental groups. They have vowed to block the massive, decade-long construction project, arguing it would needlessly generate new greenhouse-gas emissions, threaten endangered species such as big horned sheep and rip up pristine wilderness landscapes.

“The environmental destruction that would happen to the backcountry, to the parks, the mountains, it’s ludicrous,” said Matt O’Malley, executive director and managing attorney for San Diego Coastkeeper. “We would use everything within our arsenal including legal remedies to stop this.

“If you were looking for a way to unite all environmentalists in full opposition to something, this is the project you’d come up with,” he added.

The proposed conveyance system has also drawn vocal opposition from a majority of those serving on the water authority’s board, which represents the wholesaler’s two-dozen member agencies. Many of the San Diego region’s most senior water managers have repeatedly raised concerns that the project could drive up rates in the short term and wouldn’t pencil out for many decades to come, if at all.

“We just feel the pipeline would cost an outrageous amount compared with continuing our relationship with Metropolitan,” said Christy Guerin with the Olivenhain Municipal Water District, who until recently served on the water authority board. “To do that kind of tunneling and environmental damage and not acquire one extra drop of water, duplicating a pipe that already brings it to us, is bizarre in my mind.”

Twenty of the board’s 36 members voted in November to nix the project based largely on financial concerns.

However, Madaffer and his supporters were able to push through further study of the pipeline with a razor-thin margin because of the board’s weighted vote, which gives greater leverage to those representing bigger cities. Appointed by former Mayor Jerry Sanders in 2012, Madaffer is one of 10 on the board representing the city of San Diego.

In a somewhat surprising turn of events, the city of San Diego’s finance department sent a letter to the water authority a few days ahead of the November vote also raising concerns about the proposed pipeline’s $5 billion price tag. Top officials pointed out the city was already engaged in an expensive water recycling program, known as Pure Water, and could not commit to doling out more cash for the project.

Still, six of city’s representatives on the water authority’s board voted to approve further study of the project.

Opponents said they were shocked at Madaffer’s relentless lobbying and how effective it proved.

“His ability to get people to support it, given the clear facts that this doesn’t make sense, it’s amazing to me,” said Jack Bebee, general manager at the Fallbrook Public Utility District.

Madaffer is a long-time San Diego political insider. He served as a City Council member from 2000 to 2008 before starting a government-consulting firm, Madaffer Enterprises. He also sat on the California Transportation Commission for five years until early 2019.

The self-described futurist is now embarking on an 18-month-long crusade, along with water authority staff, to seek out state and federal funding opportunities as well as public-private partnerships that could help pay for the pipeline project.

“There are a lot of public-private entities out there that are interested in this project, from labor unions to major, major, global infrastructure builders.”

— Jim Madaffer, San Diego County Water Authority board member and political consultant

Madaffer told the Union-Tribune that he would abandon his vision if he could not secure enough outside funding to prevent ratepayers from seeing an even temporary increase to their water bills.

“There are a lot of public-private entities out there that are interested in this project, from labor unions to major, major, global infrastructure builders,” he said. “There’s a lot of potential to subsidize the cost of this project.

“If we would ever be paying a dime more on this project over what we’d pay MWD, I’ll be a no vote,” he added.

The Colorado River comes to San Diego

San Diego has long eyed a connection to the Colorado River through Imperial Valley. The city of San Diego even signed a contract with the U.S. Department of the Interior in 1933 to build a connection to the All-American Canal. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation finished building the canal in 1942, but the pipeline to San Diego never materialized, largely because of local infighting.

During World War II, the Navy significantly expanded its footprint in San Diego. Eager for more water, the military offered to build a pipeline connection to Riverside County, where MWD had recently finished constructing the Colorado River Aqueduct. The 242-mile conveyance system from Parker Dam at Lake Havasu on the Arizona border would eventual turn the Los Angeles area into a megalopolis and usher in a massive wave of growth throughout Southern California.

Some leaders in San Diego were still pushing for the eastern connection to IID’s new canal to solidify their independence from MWD and secure rights to the Colorado River. But President Franklin D. Roosevelt sided with the Navy and ordered that the pipeline head north.

However, a few years later, the federal government, sensing victory was close, backed out of the initial pipeline deal. By this time, San Diego was in the midst of a severe drought and desperate for a connection to the Colorado River, the only major source of water available at the time. Eventually, local leaders embraced the northern route and successfully lobbied the federal government to keep the project alive.

The San Diego water authority was formed in 1944 to finance the construction of the San Diego Aqueduct to hook into MWD’s new canal. The water authority joined the L.A.-based agency a couple years later, relinquishing its relatively small allotment on the river to its new parent agency. In 1947, Colorado River water flowed into the San Vicente Reservoir for the first time.

It’s often said that San Diego, still adjusting to the war-driven population boom, had less than a month’s supply of water when the first flows came down from MWD.

Over the years, the San Diego Aqueduct’s pipeline system was expanded to pull down more supplies from the north. For decades, 95% or more of the region’s water flowed through the water authority’s connection with MWD. Today that share is down around 70%, with desalination and water recycling coming on line.

In 1991, at the tail end of a five-year drought in California, the relationship between the two agencies soured. The feud has continued to this day.

The MWD board voted in February of that year to slash deliveries to the San Diego region by 31%. Many agencies throughout Southern California were taking deep reductions to their allotted water.

A wet miracle March staved off even worse cuts from the state, but the water authority’s rationing went on for 13 months. Officials say it took a devastating toll on San Diego’s local economy. Many of them felt the region was treated unfairly by MWD. Again local water officials started looking for alternative sources of water.

At the time of the water cuts, Madaffer was chief of staff to San Diego City Council member Judy McCarty. He and others at City Hall never forgot the experience. That included Maureen Stapleton, who as assistant city manger at the time would go on to be the water authority’s general manager for more than two decades.

“When MWD said, ‘Sorry, folks, we’re cutting back your water,’ it was at the height of a drop in the economy,” he said. “Our region lost 50,000 jobs.”

After the drought, San Diego started talking to IID about buying its Colorado River water to prevent future curtailments by MWD. By 2003, the two agencies had inked a deal. But the water authority still had to pay MWD to move the water through its aqueduct.

The proposal to build a pipeline directly to IID was resurrected as early as 1996 and reviewed again in 2002, 2012 and 2017. Each time, building a new pipeline connection to IID’s canal was determined to be too expensive and redundant with the San Diego Aqueduct system.

In 2010, the water authority started hauling MWD into court, challenging its parent agency on the cost of moving the Colorado River water. The litigation continues to this day.

Madaffer, who has sat on the water authority’s board since 2012, recently served a two-year term as chair starting in 2018. That’s when the Regional Conveyance System got fresh legs.

“When you’ve been in this business as long as I have, it isn’t like I just had an epiphany,” said the 60-year-old Madaffer. “This was just unfinished business, and I wanted to get it done. That’s what brought this study to the forefront in 2019.”

The Madaffer plan

In June 2020, the San Diego water authority presented its 36-person board with an initial study. The report, prepared by an outside consultant, found that multiple pipeline routes between the Imperial Valley and San Diego could provide “significant savings” to ratepayers in the long run as compared with continuing to pay MWD to deliver Colorado River water.

Water authority board Chair Gary Croucher, who has served on the Otay Water District board for about two decades, supported the study and further exploration of the pipeline.

“As we move forward, not being held hostage would be a good thing for us, but the key is does it make sense for us financially,” said Croucher, a retired firefighter. “We want to make sure we do our due diligence on all aspects, financially, environmentally.”

Madaffer and his supporters have been leaning toward a route through Borrego Springs, a quiet desert town at the base of the Cuyamaca Mountains. The project would include 47 miles of canals, 39 miles of pipelines and 47 miles of tunnels, as well as three pump stations and associated power lines.

The pipeline system would also likely require a roughly $1-billion desalination plant.

The water that comes out of the All-American Canal is highly salty because of the river’s natural composition and upstream agricultural runoff. MWD blends its Colorado River water with supplies from the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta to reduce its salinity levels before sending it to San Diego.

Proponents say the brackish discharge from the new desalination plant could be used to help restore the Salton Sea. The reverse-osmosis process would also slightly reduce the total amount of water the region gets from the Colorado River.

Many of the board’s most senior water managers were skeptical of the agency’s finding. They questioned whether staff, in order to make the pipeline pencil out, had exaggerated the potential for MWD to increase its rates in coming decades.

Eighteen of the water authority’s 24 member agencies banded together to commission their own independent study of the pipeline project. The report, which came back in July, found the water authority’s study was based on “highly implausible” assumptions.

The water authority suggested the pipeline could start benefiting ratepayers as soon as 2062. The member agencies’ study found that the project wouldn’t be in the black until around 2080, if not decades later.

“I don’t see this as a financially viable project,” said Kim Thorner, general manager of the Olivenhain Municipal Water District. “It’s our kids and grandkids who would be paying for this.”

In November, Madaffer and his supporters pushed through additional study of the project with a weighted vote of the board, committing the agency to spend about $4 million on the project.

Madaffer now has until the summer of 2022 to find investment partners and public funding to help shrink the pipeline’s upfront cost to the water authority. His current term on the board expires in March of that year, but he could be reappointed by San Diego Mayor Todd Gloria.

Gloria, who is slated to make several appointments on the board in coming months, almost certainly has the political power to quash the pipeline. The mayor declined to take a position on the project in response to questions from the Union-Tribune.

“As the City of San Diego moves forward on ensuring a long-term safe and reliable water supply, our top priorities are fully implementing the landmark Pure Water program and protecting the interests of San Diego ratepayers,” said Dave Rolland, a spokesman for the mayor.

Leading Borrego to water

Initially, Madaffer and others thought Borrego Springs might enthusiastically welcome the water pipeline. The desert town relies completely on groundwater and is under state pressure to ratchet down pumping to sustain its aquifer.

Water authority staff reached out to the Borrego Water District to propose storing water from its pipeline in the town’s groundwater basin. However, water managers and others have raised a host of concerns, most notably that injecting the salty river water could compromise the town’s high-quality groundwater supply.

In August, the Borrego Water District held a meeting to discuss the issue. While several community members showed up to oppose the pipeline, two of the town’s most influential landholders encouraged further study.

Those in favor included Jack McGrory, part owner of La Casa del Zorro, a luxury Borrego Springs resort, as well as a representative from Rams Hill Golf Club, owned in part by real estate investor and former Republican politician Terry Considine.

“If it has really negative impacts to the park because of some pipeline issue or whatever, we can take a look at that,” McGrory recently told the Union-Tribune, “but I think, at least in the conversations I’ve had with the county water authority, if they use our aquifer for storage, there’d be a revenue benefit.

“It’s not just a uniform aquafer,” he added. “There are pockets of good water and pockets that aren’t so good up by Rams Hill. We have to look at that.”

Meanwhile, opposition to the pipeline among long-time residents has only increased in recent months. Many people have voiced concerns that the project, which could take 10 to 15 years to complete, would destroy the town’s quiet, rural aesthetic.

Specifically, ecologists and others have warned that drilling a tunnel through the mountains could drain surface creeks and streams that many animals rely on, including horned lizards, big horned sheep and other endangered species. The pipeline would also cross several fault lines.

It would turn Borrego Springs into a construction site for years, said Mark Jorgensen, former superintendent of Anza-Borrego Desert State Park.

“How can you even consider drilling beneath a state wilderness? It’s sacrilegious,” he said. “One of the great assets of the desert is darkness and silence. This project would ruin both of those.”

Madaffer and water authority staff have downplayed the environmental impacts, saying the agency will look at those concerns if the project proves financially viable.

“There’s a lot of enviros that see the benefits this project brings to saving the Salton Sea, replenishing aquafers,” Madaffer said. “Like everything, there’s tradeoffs.

“Most of the project’s subterranean,” he added. “I don’t know how a tunnel below the floor of the Anza-Borrego Desert is going to be an impact to the flora and fauna.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.