- Share via

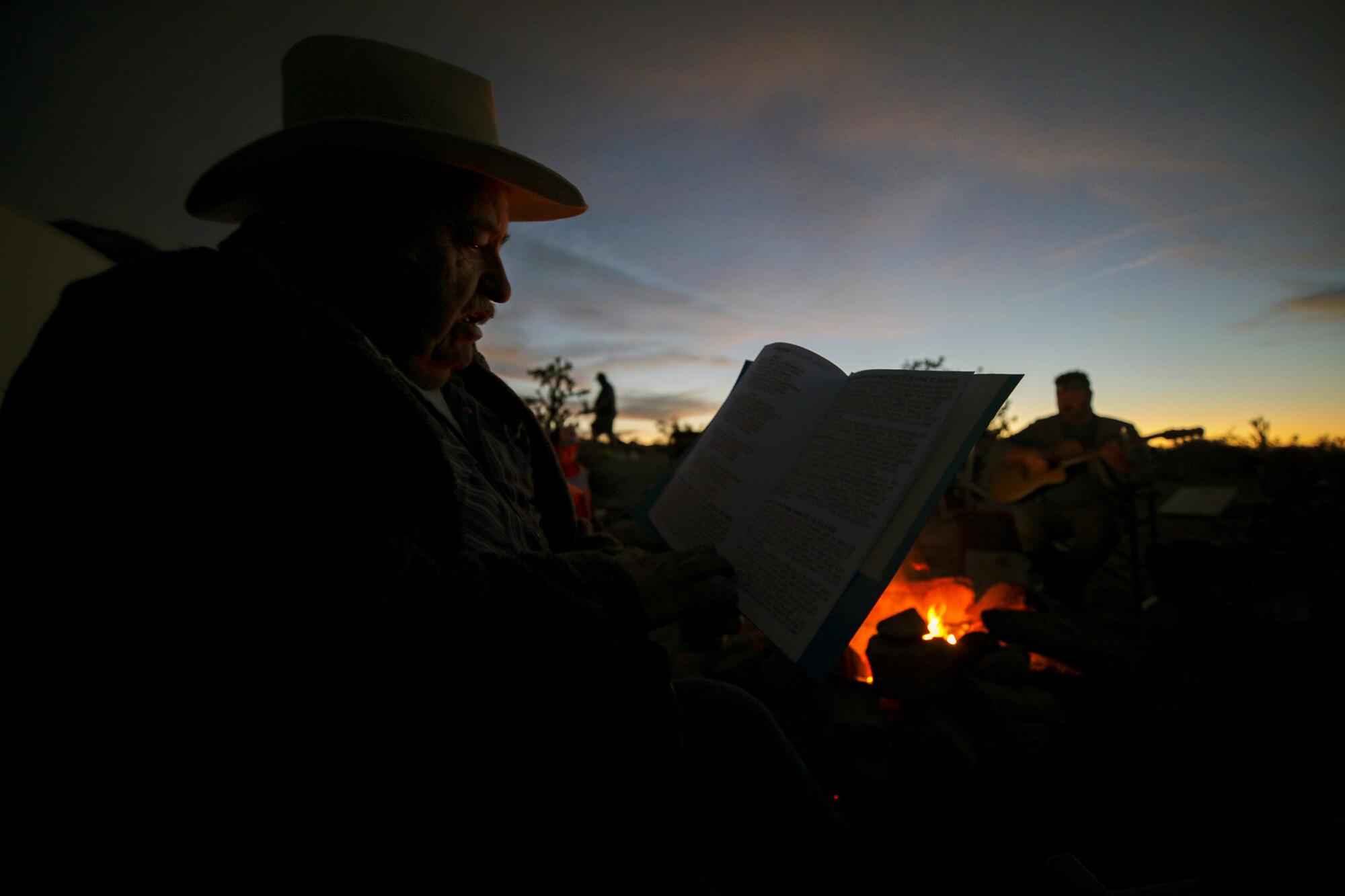

SUNRISE ROCK, Calif. — The faithful removed cowboy hats and bowed their heads for Easter service.

Nearly 40 men, women and children gathered in view of the white cross made of pipe. They sang the Easter hymn, some off-key but all in earnest.

Raise your joys and triumphs high alleluia

Sing ye heavens and earth reply alleluia

This is church, but there’s no building in sight in this remote section of the Mojave Desert. There are no pews, just green and red camp chairs placed beneath the branches of a juniper tree. The worship and service hymnals are printed on white paper, the pages stapled together proclaiming “Resurrection Sunday.”

Since at least 1935, worshipers have gathered at this spot off Cima Road, six miles south of Interstate 15, to celebrate the Christian holiday.

The parishioners arrived during the decade the cross was wrapped in a tarp, fastened at the base by chain and a padlock, and later covered with a plywood box amid a battle over the separation of church and state that would wind up before the U.S. Supreme Court. They assembled even when the cross was stolen in 2010.

For some, last year was the first service they’d missed in decades and only because the COVID-19 pandemic made a reunion dangerous.

“This is the first thing I got robbed of last year,” missionary Larry Craig told his desert congregation. “2020 was the year of the great robbery. Everything I planned on doing all summer long was taken away from me.”

This Sunday morning was the first sunrise service of the pandemic. It was a sign that, out here in the desert, where the cross is bolted to a granite outcropping known as Sunrise Rock, life and worship are returning to normal.

The cross, in various forms, has stood at this spot since 1934. It was erected by the Veterans of Foreign Wars, including a miner named J. Riley Bembry, and its intent was to memorialize veterans of World War I.

The veterans picked the spot because a color shading on the rock looked like the shape of a soldier.

Linda Maria’s first memory of the Easter service was around 1964, at the age of 9 or 10, when it was hosted inside a boxcar near Sunrise Rock. Even after the boxcar was vandalized and burned, people kept coming.

“I don’t know if it’s just because the cross was on the rocks or what started that ... it was just something we did and carried on,” the 65-year-old said. “It was an important place for the community.”

Although not particularly religious, Bembry, who served as an Army medic during the war, had agreed to look after the icon of Christianity. Before he died in 1984, Bembry asked his close friend, Henry Sandoz, if he would take over that responsibility. Sandoz said that he would.

“Henry was a man that really, you know, he told somebody he’d do something, he was going to do it,” said his wife, Wanda. “It was so important to him because of his promise to his friend and because of what that cross stands for.”

Henry and Wanda took their responsibility as caretakers seriously. Wanda, a school bus driver, had a route that ran along Cima Road, and she would check on the cross nearly every day. The times it was knocked down or vandalized, Henry would replace it.

On Palm Sunday in 1998, in an attempt to keep the memorial safe, Henry and some friends bolted a cross made of 5-inch-diameter pipe to the granite and filled it with concrete. The next year, the trouble began.

At issue was the fact that Sunrise Rock was in the Mojave National Preserve, on federal land. In the fall of 1999, after the superintendent of the preserve received letters from the American Civil Liberties Union urging that the cross be removed because it was a violation of the 1st Amendment, she asked the Sandozes if they would consider taking it down.

“Henry said not just no, but hell no,” 77-year-old Wanda recalled. “He said, ‘I put that cross up to stay and I’m not taking it down.’”

In 2001, a former National Park Service employee, with the backing of the ACLU, filed a lawsuit against the agency. A judge ordered that the cross be covered until the matter was resolved. Easter service went on regardless.

“To have a box on it just meant that someone out there thought that that was going to change what we were doing. It wasn’t going to change us gathering together,” said 40-year-old Larisa Craig, who as a child would spend the night in a van in 30-degree weather so her father could give the sermon on Easter Sunday.

“This is not just a sacred spot because there’s a cross up there. It’s a sacred spot because of the people who came together.”

The congregants watched as the battle over the cross dragged on for more than 10 years. Among the lawyers defending the cross was now-Sen. Ted Cruz.

Because the only way the cross could remain was if Sunrise Rock were privately owned, a compromise was arranged: a land swap between the Sandozes and the park service. The California office of the Veterans of Foreign Wars would take ownership of the property around the cross.

Although a district court ruled against the compromise, the U.S. Supreme Court eventually took the case and determined that the ruling was flawed. The district court reconsidered and eventually approved the transfer.

“This was something worth preserving … for every generation that came long after us,” Larisa Craig said. Community members have held dedication ceremonies for grandchildren, celebrated weddings and mourned loved ones.

The cross has been a fixture for many, including Linda Maria, who is now 65. She was married there in 2006 (her husband removed the plywood box for their wedding photos). Her granddaughter was dedicated there. Eleven years ago, she got a call while camping at Sunrise Rock that her grandson was being born. Afterward, she returned to gather with everyone in the desert.

When Henry Sandoz died in 2015, his memorial service program featured a picture of him — cowboy hat on his head — with the cross in the background. Also included was the reference to his “successful fight to preserve a war memorial in the Mojave Desert.”

His granddaughter, Audry Wilcox Ledua, was dedicated at the site when she was 5 months old. She planned to have her wedding there last May until COVID hit.

“It has such a meaning in our family,” the 22-year-old said. “It’s definitely one of my favorite places.”

Wilcox Ledua and her husband drove down from Cedar City, Utah, on Friday so they could attend the Sunday service. The couple, who ended up getting married last April, celebrated their first anniversary that day.

By 7 a.m., people formed a semicircle around a crackling fire that kept them warm in the cold breeze. Some drove down from Baker and Boulder City, waking as early as 3 or 4 a.m. Larry Craig — who lives around 90 miles away in Newberry Springs — continued the tradition of camping out, this time with his wife, three kids and seven grandkids (the fourth generation to worship at this spot).

Craig, who has been doing the service for more than 30 years, started with a half-moon still up in the clear blue sky. Soon after, the group watched together as the sun rose over Kessler Peak, bathing the cross in light.

There was no dress code — parishioners wore blue jeans and sneakers or cowboy boots. Craig’s daughter-in-law called it the “cowboy sunrise service.”

After Mass, the group snacked on fruit, yogurt and Wanda Sandoz’s famous cinnamon rolls as they caught up with friends. The children scrambled up the rocks leading to the cross.

Some wouldn’t see each other again until the next Easter Sunday. It’d be another year until Craig’s next sermon at Sunrise Rock.

If you ask the 67-year-old how long he’ll lead the service, he’ll tell you: Until Jesus takes him home.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.