- Share via

How many times have those of us who seek out and appreciate Los Angeles history bemoaned the loss or threatened loss of those places that help us feel and connect with its past?

The big buildings on our main streets where important things happened. The small bungalows on our side streets where long-ago families set down roots and grew. The favorite gathering spots that have anchored our neighborhoods for year after year after year.

The wildness, whimsy and variety of our signs, structures and settings that make our city so textured and full of surprises despite its undeserved reputation for (and too many demolition-bent developers’ default to) blandness.

Save the Cinerama Dome! That’s been the rallying cry since news broke that the ArcLight Cinemas and Pacific Theatres chains, long shuttered by the pandemic, were closing up shop for good. Last I checked, an online petition to keep the dome intact as a theater had gathered over 21,000 signatures.

I love and support that concern for the dome and for its long service to cinema. I hold out hope that the noise people are making about it combined with a degree of protection already in place ultimately will keep the dome safe.

I’m here to argue, however, that we need to spread this same preservation passion to so many other perhaps lesser-known but greatly deserving places in our city. Many of us mourn communities and buildings and amazing history that the city should have held on to but didn’t. But we still have a lot more to lose and so much more history to safeguard. And more of us need to play a role.

You don’t have to be a professional to fight to save something in L.A. that you think is worth saving. You can try to protect it before it is threatened. You can do historical research to strengthen the case you make for why it needs to be preserved. You can organize to safeguard your neighborhood’s architectural history. You can stand up and shout, “This place matters.”

The ArcLight Hollywood with its Cinerama Dome means a great deal to Hollywood the neighborhood. Here’s hoping for a rescue that saves it but doesn’t try to reinvent something that works.

Just as I was writing to you about the dome and what it means to my Hollywood neighborhood, a new book by the person who directs the city’s historic preservation efforts serendipitously landed on my doorstep.

Ken Bernstein runs the Planning Department’s Office of Historic Resources, Los Angeles’ historic preservation program, as well as its Urban Design Studio, whose brief is to try “to elevate the quality of public and private design in order to create a more vibrant, livable, walkable, and sustainable city.” He spent eight years as the director of preservation issues for the L.A. Conservancy, the nonprofit whose countywide campaigns have been behind saving so much of value to people in our area. (The conservancy was founded in 1978, in fact, to fight the proposed demolition of our Central Library, a fight I think we’re all glad was won.)

Bernstein knows more than almost anyone about preservation in Los Angeles — and his “Preserving Los Angeles: How Historic Places Can Transform America’s Cities” is a toolkit for the rest of us who want to learn about the city’s various preservation programs and what it takes to harness them. It explains, for instance, the outreach and education involved in trying to safeguard a neighborhood’s architectural character by getting it designated a historic district. Los Angeles now has 35 such historic preservation overlay zones, or HPOZs, covering more than 21,000 properties.

“Preserving Los Angeles” also includes the firsthand accounts of people who have fought to hold on to our past. It describes the manifold benefits they’ve found in doing so. They’ve drawn fresh eyes and new life to places that were being overlooked. They’ve strengthened the feeling of community in their neighborhoods. They’ve gotten people to visit parts of the city they used to avoid. They’ve educated residents inclined to want the new and shiny to appreciate the value of the old and full of stories.

“Preservation ultimately is about people,” Bernstein told me. “It’s people who give life and meaning to places and people whose passion and commitment makes preservation happen.”

His book highlights many such labors of love.

Did you know that the city of Los Angeles has landmarked 1,221 historic-cultural monuments, or HCMs, — among them not just buildings, old and not so old, humble and grand, but trees and murals and bridges? That anyone can nominate a new one? That they include Eagle Rock, the actual physical outcropping (HCM No. 10), and the 218 Mexican palm trees planted for the 1932 Olympics that line Avalon Boulevard in Wilmington (HCM No. 914)? That HCMs can be found all over the city in places you might not expect?

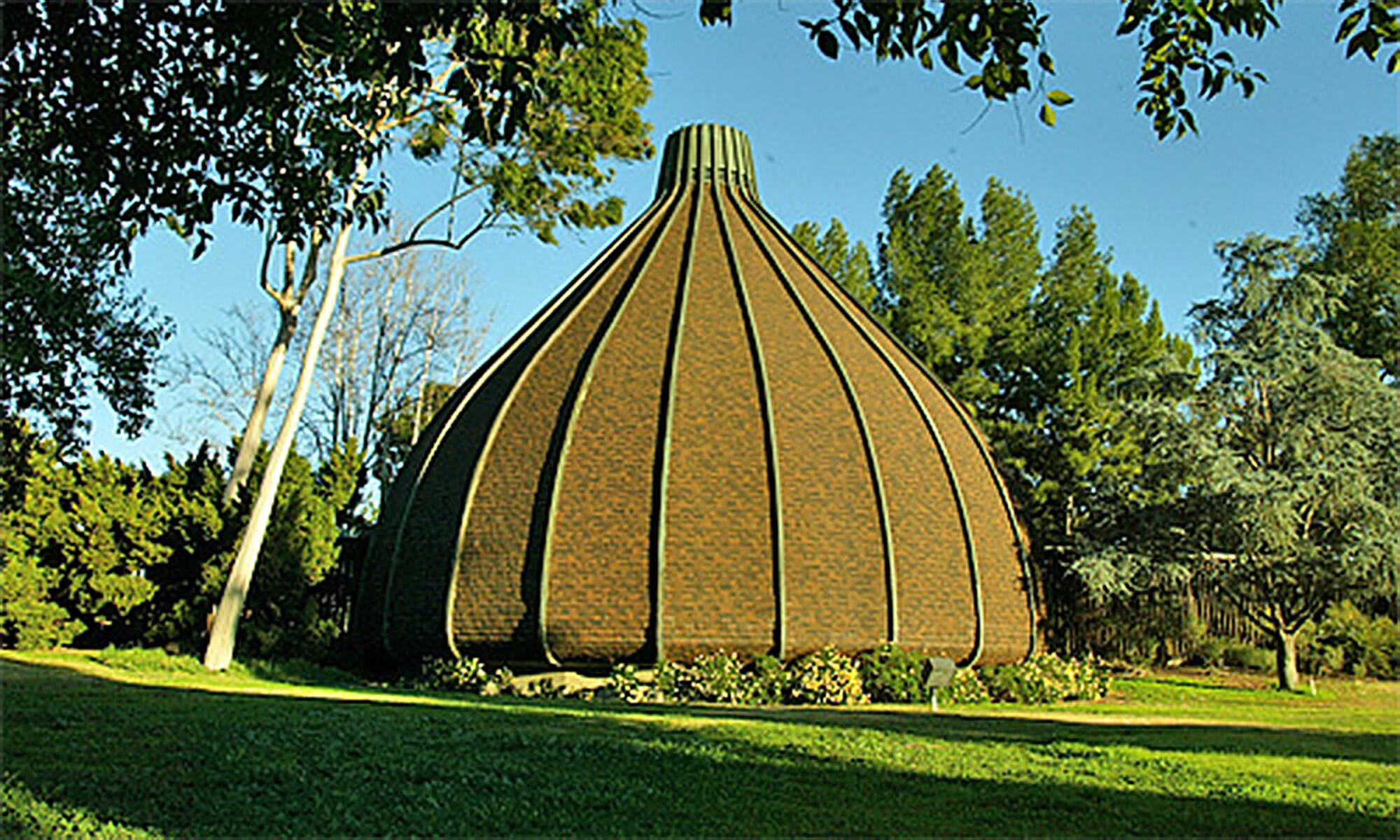

Have you ever seen HCM No. 975, the Sepulveda Unitarian Universalist Society sanctuary on Haskell Avenue in North Hills, a midcentury building known as the Onion because it looks like one? It’s architecturally interesting but also deemed worth protecting because of its social and cultural history as a center for protest during the Vietnam War.

Places plain to look at, oddball places, places that showcase our city’s particular ways of doing things can be landmarked because of their stories, because of the significant people associated with them, because they represent our cultural history.

Did you know that the Munch Box, a 1950s-era burger stand in Chatsworth is HCM No. 750, so designated because it’s a fine example of the walk-up food stands we love in L.A.? That the New Temple Missionary Baptist Church in South L.A., where Aretha Franklin recorded her 1972 live gospel album “Amazing Grace,” is HCM No. 1194?

I don’t know about you, but I like my Los Angeles served with a big scoop of Wild West on top.

The Cinerama Dome and its marquee constitute HCM No. 659, designated just 35 years after construction, when the same owner that recently announced that the theater will shut down proposed a development plan that would have obscured views of the dome and greatly altered its interior.

Landmarking does not guarantee that the places we care about last forever — but it makes it much harder and slower to demolish them and often leads developers to abandon or revise their plans to make them more palatable.

What happened with the Cinerama Dome is a perfect example. The owner came up with a new design for expansion, the dome remained plain to see, and the modern multiplex that the dome became part of also grew to be beloved to many.

In his book, Bernstein stresses that preservation doesn’t mean freezing time. Instead of tearing down buildings, owners, with city support, can rehabilitate them and adapt them to suit their modern needs — as can be seen by the thousands of apartments that now fill former office buildings in downtown L.A.

He talks about SurveyLA, the massive citywide effort completed in 2017, to go block by block across our 466 square miles and identify and contextualize our historic resources, about the way the city is now using that information and gathering more to try to protect a greater diversity of places that match the diversity of its people — that help preserve the history, for instance of Black Americans, Latinos and Asian Americans. There’s a lot of work to be done. Right now, only 6% of the city’s HCMs are associated with people of color.

On Thursday, he and I met in Lincoln Heights, one of the city’s oldest neighborhoods and a historic district. We stood inside HCM No. 807, the Church of the Epiphany, the oldest operating Episcopal church in the city. Its architecture is noteworthy. Its original building dates to 1887. But it is just as notable for the fact that Cesar Chavez used to speak there and the newspaper La Raza was put together in its basement, where leaders of the Chicano Moratorium and the East L.A. student walkouts met to plan and organize.

Outside, across the street, we saw a boxy, modern stucco apartment building but also a quaint little long-ago cottage, with decorative spindlework and an inviting front porch held up by dainty posts.

By the time I made it home, Bernstein had looked up that cottage, which had been identified in the neighborhood’s preservation plan as Queen Anne style, built in 1895.

I was glad to see that history still standing. I was glad for the window it gave me onto an earlier city.

Do you have places that are special to you in the city, that you think help tell its story? Look around you. Pay attention. Go to HistoricPlacesLA, the city’s online site focused on our historic resources, and find out more. These places don’t save themselves. They need us.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.