Commentary: The art world knew him as Eli. How Broad was friend and foe to museums

You know you’re a big deal when everyone in your field knows who you are just by hearing your first name.

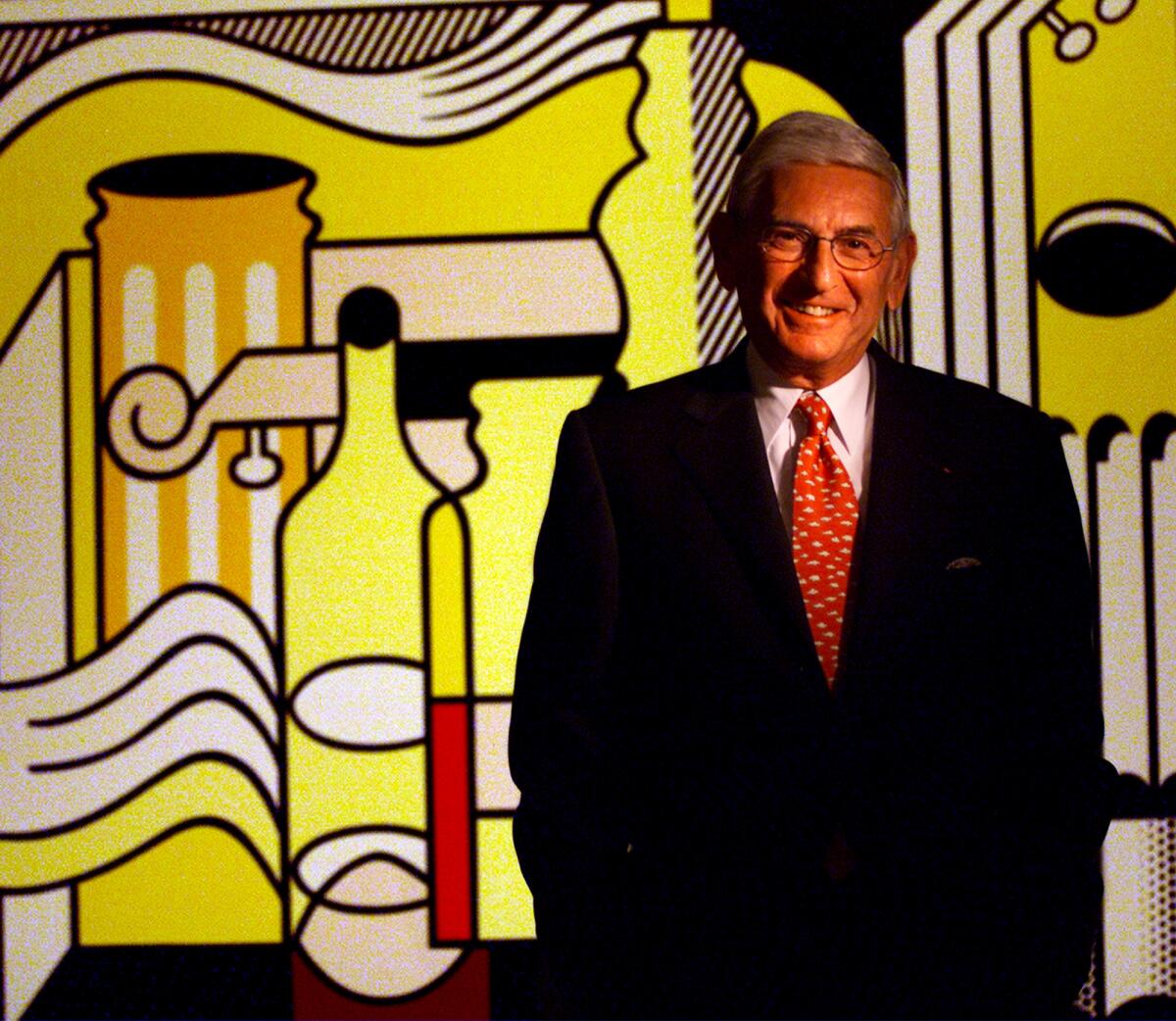

Lots of rich people populate the international art world. But say “Eli” wherever you go in those serpentine precincts, and everyone knows you mean Eli Broad. In that regard he was the art world’s Cher.

He couldn’t sing, but he especially loved Pop art and its descendants, amassing superlative collections of paintings, sculptures and photographs by Jasper Johns (42 works), Andy Warhol (25), Roy Lichtenstein (35), Ed Ruscha (45), John Baldessari (42) Cindy Sherman (127), Jeff Koons (36) and more. When he committed to the work of an artist, he understood the importance of collecting the artist’s work in depth.

His vast wealth — estimated at the time of his death at 87 on Friday at nearly $7 billion — made it possible. But he also could use those funds in surprising ways.

Eli Broad, a billionaire philanthropist and art collector, played a central role in building such Los Angeles institutions as Walt Disney Concert Hall and the Museum of Contemporary Art before building his own museum, the Broad.

When he dropped $2.47 million on “I…I’m Sorry,” a classic 1964-65 Lichtenstein comic-book interpretation of a weeping art collector-turned-dealer Holly Solomon in 1994, he paid by credit card. The card company was offering a mile-per-dollar deal underwriting air travel expenses, so Broad pulled down 2.47 million free air miles along with the masterpiece painting.

He donated the mileage to the California Institute of the Arts so that students could travel — a marvelous gift that, notably, also gave him a large charitable tax deduction. The credit card company promptly changed its mileage rules.

Eli came by his name recognition for good and for ill. Instrumental in helping Los Angeles become one of the most prominent cities internationally for contemporary art, he was also a bull in the newly emerging china shop of L.A. museums.

At various times he served as a trustee at the Museum of Contemporary Art, the UCLA Hammer Museum and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Ultimately, despite ups and downs, the institutional relationships did not go well.

Broad had a hand in a Renzo Piano building at LACMA, the Frank Gehry-designed Walt Disney Concert Hall and his own museum, by Diller Scofidio + Renfro.

Like many self-made billionaires, Broad was firm in his conviction that he knew best. Otherwise, how would a lower-middle-class kid from the Bronx have become so rich?

He was instrumental in bringing the stellar collection of 80 works acquired by the groundbreaking Italian collector Giuseppe Panza di Biumo to the new Museum of Contemporary Art as a gift purchase in 1984 — a move that gave instant international credibility to the fledgling institution. But the road soon got bumpy.

I was awakened at 3 a.m. one day by a phone call from Milan from a flustered Panza, who was horrified that Broad, as MOCA board president, was planning to peel off a Mark Rothko painting, maybe one of 11 Franz Klines and perhaps a Robert Rauschenberg “combine” sculpture to send to auction in New York to raise the funds that would pay off the purchase portion of the deal. Fundraising for the purchase had lagged, but rather than write a check — which he certainly could afford — Broad thought it sensible to let the acquisition pay for itself.

The huge outcry when the scheme went public foiled the plan.

The arrangement was strictly rational as a business deal, but it would have wrecked MOCA’s reputation. What important collector would ever engage with the museum again? Broad was never really able to separate his sharp business acumen from his philanthropic activity. He tried to impose his for-profit success on the nonprofit museum sector, regularly creating havoc.

Broad was at the leading edge of a new generation of problematic philanthropists, who believe social good can itself come from the pursuit of profit, rather than from traditional charity. With a focus on the bottom line, he saw the sign of an art museum’s success as tied to its box office, rather than its more elusive artistic achievement. In 1972, he had been co-chair of the political group Democrats for Nixon, which spoke to the dissonance that characterized his museum involvements.

Broad’s decision to open his own art museum on Grand Avenue in downtown Los Angeles was emblematic of the man and his convictions. He was influential in choosing directors to lead the city’s museums, including former UCLA Vice Chancellor Andrea Rich at LACMA and New York art dealer Jeffrey Deitch at MOCA — neither of whom had a lick of prior museum experience.

As the art market continued to explode, the Deitch experience saw troubling intersections of nonprofit and for-profit projects at the museum. Rich gave Broad cart-blanche to construct a museum-within-a-museum at LACMA, bizarrely named the Broad Contemporary Art Museum and paid for with the collector’s gift of at least $50 million.

Photos: Eli Broad, philanthropist, art collector, builder, created part of the Los Angeles landscape

Eli Broad, philanthropist, art collector and builder, has died at 87.

When Rich became ill and stepped down from the directorship, Broad was instrumental in bringing Michael Govan from New York’s DIA Foundation to fill the job. Once installed, however, Govan rightly balked at Broad’s plan to run the new BCAM as a semi-independent operation. On the eve of the building’s opening, the collector took his art and walked.

Broad followed in the footsteps of prior art benefactors like Norton Simon and Armand Hammer. They too were unable to surrender control to publicly minded institutions, establishing their own museums instead. The one L.A. museum that kept him at arm’s length was the Getty, which had no need for his money.

Ironically, for all his vocal support of risk-taking art and of L.A. as a burgeoning center for new art, Broad was ultimately conservative in his collecting habits. When he began in the 1980s, he was forming two collections simultaneously: one personal, which is where he spent large sums of his own money on blue chip art; the other corporate, where he bought work by emerging Los Angeles artists using funds from Kaufman & Broad, his home-building company.

Eventually a number of post-1960s L.A. artists themselves became internationally established, including Chris Burden, Lari Pittman and Robert Therrien. All are now well-represented among the 2,000 pieces in Broad’s museum collection.

But when BCAM opened with selections from Broad’s collection in 2008, fully 80% of the 176 works were by artists who had shown with a single gallery — Gagosian, commonly considered the leading commercial powerhouse. For the cultural life of the city, Broad was a die-hard populist, but there were limits to how far he would go. Tellingly, for all the greatness of his collection — and it is great, with extraordinary works — only Sherman ranks as an untried artist whose reputation he was instrumental in securing.

The rest were first championed elsewhere, and Eli eventually got on board.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.