California sees record number of guns confiscated under ‘red flag’ law

- Share via

SACRAMENTO — Five years ago, California became one of the first states in the nation to enact a so-called red flag gun law, allowing family members and police officers to ask a court to block those believed to be a risk to themselves or others from having firearms. Now, as other legislatures weigh adopting similar laws, state officials said Friday that a record 1,285 gun-violence restraining orders were issued by judges in California last year, temporarily removing firearms from people deemed a danger.

Though many courts were operating under restrictions or remotely because of the COVID-19 pandemic, they received petitions for the orders at a greater rate than the year before, when guns were taken from 1,110 people.

“I’m glad that Californians have a tool to intervene to save lives and prevent tragedies,” said Assemblyman Phil Ting (D-San Francisco), who authored a bill last year that expanded those eligible to ask judges for orders to employers, co-workers and school employees.

The law took effect in in 2016 following the 2014 attack in Isla Vista near UC Santa Barbara in which six people were killed and 14 were injured when a 22-year-old man went on a rampage of shooting, stabbing and striking people with a car before killing himself. Family members of gunman Elliot Rodger had alerted the police that they were concerned about his behavior, but officers who checked with him were not aware he had bought guns.

The first “red flag” law was adopted by Connecticut 22 years ago, followed by Indiana in 2005, and California in 2016.

California’s law takes a slightly different approach and is the model for many of the 15 other states that have since adopted such measures, according to Dr. Garen J. Wintemute, a professor of emergency medicine and director of the Violence Prevention Research Program at UC Davis.

Lawmakers in other states, including North Carolina, have proposed that they also adopt a “red flag” law.

The report released Friday comes a month after the Biden administration called on Congress to pass a national “red flag” law, as well as legislation incentivizing states to pass similar laws of their own. In addition, the U.S. Department of Justice plans next month to publish model “red flag” legislation for states.

“Gun violence takes lives and leaves a lasting legacy of trauma in communities every single day in this country, even when it is not on the nightly news,” the White House said in an April 7 statement announcing the actions.

A representative of the National Rifle Assn. said Friday that the organization needed more time to review the findings of the state report before commenting.

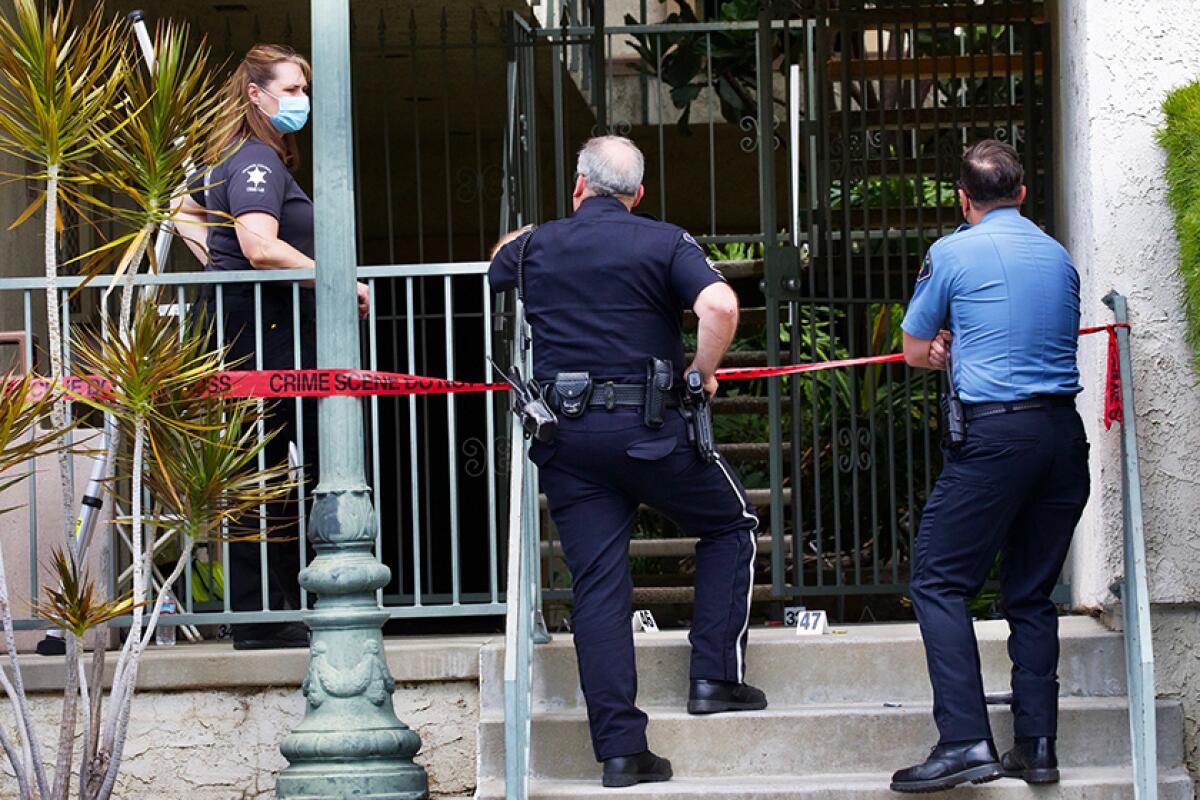

The momentum for gun safety laws has grown after a series of mass shootings this year, including one in March in which four people were killed in the city of Orange.

California’s law allows orders to be granted to immediately remove guns for 21 days, with the potential to extend the order to a year after a court hearing. Orders can also be sought for up to five years with a court hearing.

A study last year by Wintemute’s office said it appears the law is having an impact on gun violence. Researchers looked at 21 cases in which orders were issued in an effort to prevent a mass shooting. In most of the cases, people had made explicit threats of gun violence, and the study found none of the 21 individuals carried out shootings.

“In every case, there is evidence that gun violence might have occurred without the order,” he said. “If that evidence doesn’t exist, the order can’t be issued.”

Still, the use of the law got off to a slow start in California, with only 85 orders sought in the first year after it was enacted.

Wintemute credited outreach and aggressive actions by some local law enforcement agencies, including in San Diego and Orange counties, which led the state last year with 483 and 140 orders, respectively. Los Angeles County had 30 orders last year.

“Local champions make a big difference, as the San Diego experience makes clear,” Wintemute said.

Ting said San Diego City Atty. Mara Elliott has been a leading champion of the use of the restraining orders.

A spokesman for Los Angeles City Atty. Mike Feuer said the prosecutor “strongly supports” the use of gun-violence restraining orders.

“Our office will continue to work with L.A.’s law enforcement leaders to expand the issuance of GVROs,” said spokesman Rob Wilcox.

The record number of orders issued in California was encouraging to Christian Heyne, vice president of policy for Brady, which advocates for gun control laws.

“Extreme risk laws, like California’s, save lives,” Heyne said. “This is a tool that families and law enforcement can utilize to ensure the safety of their loved ones, themselves and the entire state.”

While the pandemic may have interrupted the operations of the courts that issue the orders, Ting said it might also have had an effect to increase the number of guns seized.

“The COVID-19 restrictions that kept people home may have influenced the rise, making them more mindful of the behaviors of others and open to seeking help from law enforcement or the courts directly,” Ting said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.