Has the Golden State lost its luster? California population shrinks for the first time ever

- Share via

In January 1963, Californians were told they had reason to celebrate. By the slim margin of 31,000, the state had become the most populous in the country, finally edging out New York.

Gov. Pat Brown proclaimed an official day of observance, and the state Chamber of Commerce urged every Californian to mark the occasion by “blowing his horn, tooting his whistle, ringing his bells and shooting the village cannon,” according to the Los Angeles Times.

As much as history was made then, the announcement Friday — that the state’s population has declined for the first time in its history — is equally historic.

California lost 182,083 people in 2020, though it remains the most populous state, with just under 39.5 million residents. The state will lose a congressional seat for the first time, based on slower growth reflected in the 2020 census.

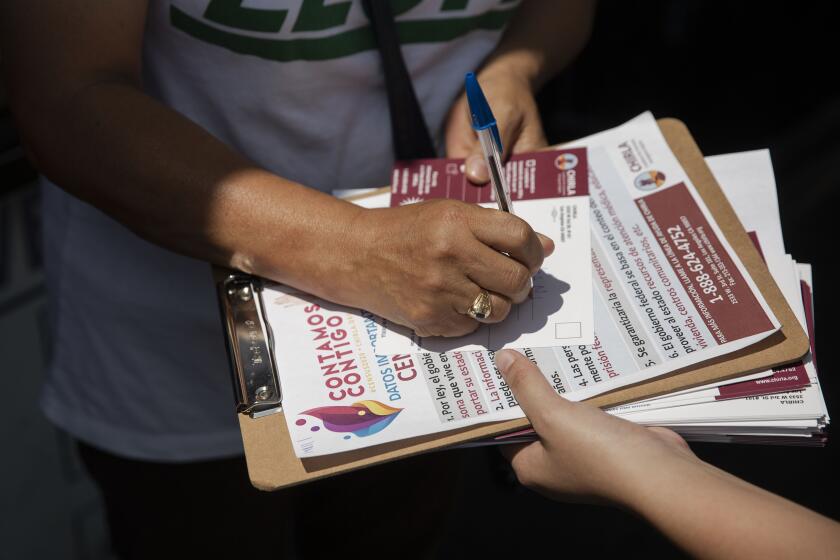

State Department of Finance officials attributed the one-year loss on a declining birth rate, reductions in immigration and an increase in deaths because of the coronavirus, which killed 51,000 people last year. They also said that as pandemic-related deaths decline, and federal immigration policy changes, California is expected return to growth in 2021.

But for some, explanations were not enough.

Census results show that for the first time in our 170-year history, California will lose a congressional seat.

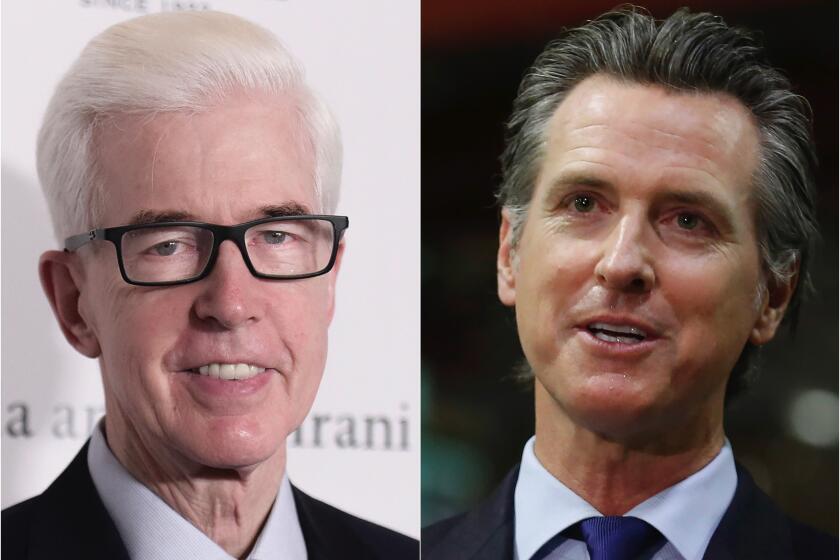

John Cox, a Republican who has declared himself a recall candidate for governor, used the occasion to denounce Gov. Gavin Newsom and other state officials for the decline. “They are driving thousands of families from California,” Cox tweeted.

But beyond blame and pronouncements lies a more fundamental question: Has the Golden State lost its luster?

“California has been a magical landscape for the rest of the world,” said Dana Gioia, former poet laureate for the state. “But it wasn’t just about Hollywood or the quick fortunes that could be made here. It was about the dream of a good life for the ordinary person. That dream didn’t require being rich. It just required being engaged.”

Gioia recalls growing up in Hawthorne in the 1960s among immigrant families who felt fortunate not just to be in the United States but in Los Angeles.

“California represented the dream of the common man and woman,” he said. “Now it’s changed. Now it is a place that represents the dream of the elite and the affluent, and that’s an enormous loss for the state.”

In a recent report, the Public Policy Institute of California echoed those sentiments, detailing the “California exodus” and its “power to reshape the state.”

A major force in California’s falling population has been people leaving for other states, according to Hans Johnson, a senior fellow at the institute. In the last decade, about 6.1 million people left California for other states, and 4.9 million moved to California from elsewhere in the nation.

The forces pushing people out of the state are changing who comes to the state. People who move to California are more likely to be employed, earn high wages and have higher education levels than those who move away, according to the institute.

“The larger picture painted by these trends illustrates the economic challenges faced by many lower- and middle-income Californians,” Johnson wrote. “The state’s high cost of living, driven almost solely by comparatively high housing costs, remains an ongoing public policy challenge — one that needs resolution if the state is to be a place of opportunity for all of its residents.”

In 1949, journalist Carey McWilliams famously positioned California as “the great exception among the American states,” a place of unique dynamics where a gold rush started 100 years earlier was still taking place. Population growth was at the center of that boom, McWilliams wrote, explaining the reasons for the state’s attraction.

Today, Californians are left trying to explain its residents’ disaffection. While some point to taxes, housing costs and urban decline, such perspectives fail to take into account the special treatment that California received at the end of World War II.

“California is becoming more ordinary,” said cultural historian D.J. Waldie, who is reluctant to fall into a “declinist narrative that points to any inevitable downward trajectory.”

“What we are seeing here is a change in how American communities structure themselves and why people live where they live,” he said Friday. “One reason why millions of people came to California is because the federal government spent billions of dollars building a defense-industry infrastructure here. Workers had to go where the jobs were. But in a knowledge-based economy, jobs can be anywhere.”

In addition, California’s exceptionalism was built upon both its natural resources — oil under Los Angeles and the rich soil of the Central Valley — and its sheer newness, which played a significant role in successive waves of migration that began at the beginning of the 20th century.

But as historian Philip Ethington at USC points out, “Golden ages don’t last forever. The movie industry is now worldwide. Computer technology has gone to China. Aerospace has moved out of Los Angeles. We don’t have monopoly on those leading-edge technologies anymore.”

Ethington also considers the “carrying capacity” of a state that was developed and overdeveloped decades ago and whose infrastructure is severely burdened. But beyond practical limitations, California is also at a reckoning point for its identity, which at times borders on myth and nostalgia and falls short in understanding its “internal contradictions.”

“The American period of California was founded in conquest and injustice,” he said, “and the conquerors didn’t treat existing populations very well. Anglos were saying that this place was meant for them, and those who ruled before were worthless. That’s the myth-building. That myth has been falsified.”

A look at 2003 vs. 2021 shows how much the state has changed since the last gubernatorial recall attempt

By shedding the past, Californians have a better opportunity to understand their future, said Waldie. “This imposes on Californians the burden of imagining their state in a new way,” he said. “The image of California that some of us grew up with won’t help us understand the California of tomorrow.”

Historian Bill Deverell, director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West, finds reasons for optimism in these possibilities.

“History tells us there are patterns and cycles here,” he said, and we should not put our faith in passively accepting the next steps of the cycles. “But instead, we should actually work harder when these hard questions come up.”

This is not to “minimize the level of distress and challenge in contemporary California by any means,” he said, but these census numbers are “not an indication that the California dream is kaput.”

Times staff writer Soumya Karlamangla contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.