This school district has not reopened. The trauma and loss from COVID-19 was just too great

- Share via

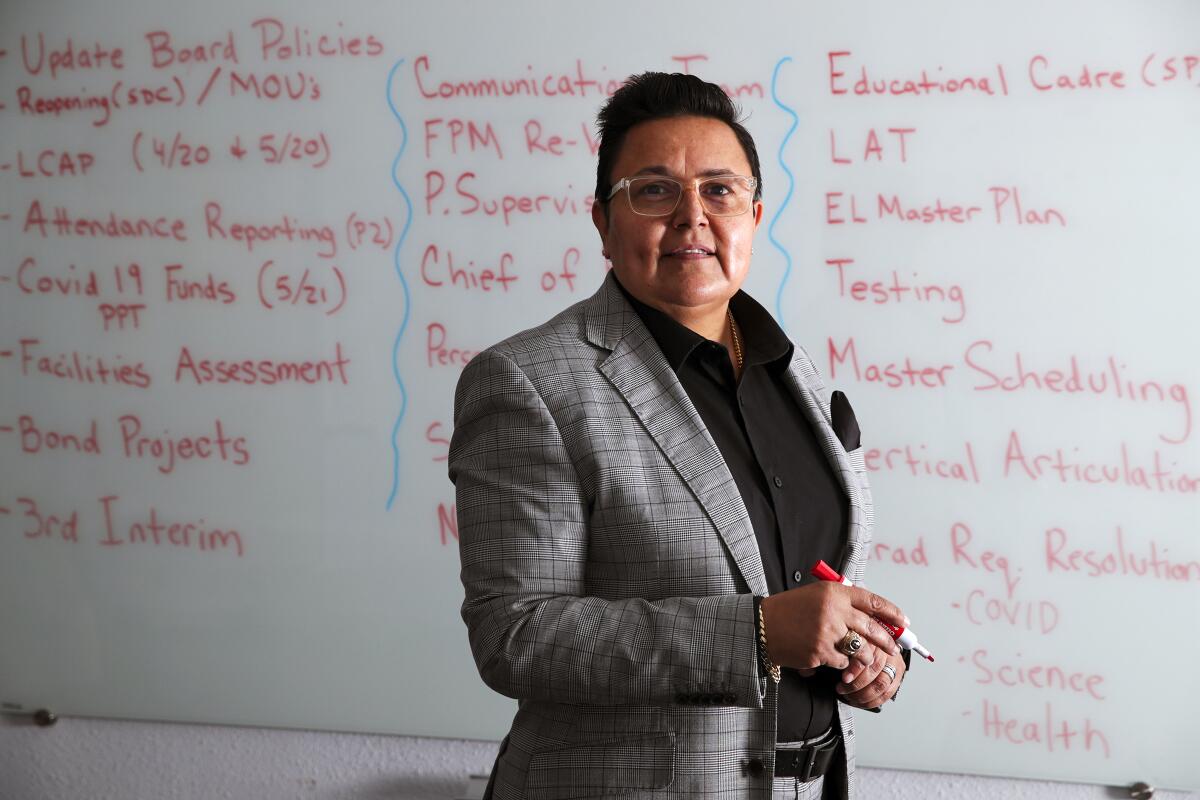

Supt. Frances Esparza knew of too many parents who had called seeking an excused absence so their child could attend a funeral. She had read too many emails saying students missed classes because a family member was hospitalized.

At the middle school alone, at least 10 students had lost an immediate family member. And those students were just the ones who had come forward.

So at a time when Los Angeles County and California are experiencing a newfound sense of optimism that the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic has passed, Esparza made a difficult decision. Hers is a school community where the losses among children, families and staff are still too raw, too recent.

Last month she announced, with the support of the school board, that the El Rancho Unified School District serving Pico Rivera would stay closed for the remainder of the school year.

“The families of Pico Rivera suffered many losses throughout the COVID-19 pandemic,” Esparza said. “Some of the students in El Rancho lost a parent, a grandparent, and some even lost both in just a few days. The staff of El Rancho Unified have also suffered the losses of family, friends and co-workers.”

The decision, she said, acknowledged that reopening schools especially in hard-hit areas like hers would take more than safety protocols, falling infection rates and increased vaccinations. Moving forward, learning will be entwined with mourning.

“We can’t just pick up where we left off,” Esparza said.

The pandemic surged in the school district after Thanksgiving, as it did in much of California and the nation. The case rate in Pico Rivera surged to 119 per 10,000 residents. By January, it reached 130.

The number of students needing counseling for anxiety, depression, grief and loss began to rise exponentially. Week after week, reports of the pandemic’s reach enveloped this working-class community.

Students have lost fathers, mothers and grandparents. At least six district employees have died in the last year, including two from COVID-19. One of the district’s unions sent out nearly a dozen $50 bereavement checks to grieving members — in a typical year, it might send out one or two.

“I was just blown away,” Esparza said. “It was so sudden, happening in a matter of weeks.”

The school district’s student population is 97% Latino. It is tucked in Pico Rivera, a suburb southeast of Los Angeles that is 90% Latino and largely working class, a group that has been disproportionately burdened by the pandemic. In this town of 64,000 residents, where the school district is the largest employer, more than 260 people have died from COVID-19, and more than 11,000 have become ill.

“Despite this tragedy that we’ve experienced,” Esparza said, “I’m proud to say that we’re healing together.”

Vaccines have been available for teachers since February, and nearly 90% indicated they intended to get inoculated. El Rancho High School, in the heart of the city, has become a vaccination site for the community.

The school district invited high-needs students back to campus in May for in-person instruction, while all others will continue distance learning.

Summer will begin a new chapter in the district, with families having the option of attending in-person or online classes. School aides and teachers will receive training to identify signs of trauma or mental health issues in students before beginning an extended summer school program.

“We need to deal with what has happened,” Esparza said.

—

One evening in March, 17-year-old Hailey Moreno and her family began another night of a novenario, a nine-day period of prayer that follows a death, over Zoom. Behind their house, she could hear the whistles of a football practice at El Rancho High, a sign that school life was beginning to rebound.

Rosaries in hand, the family prayed. Their sorrow began in January when Hailey’s father, Arturo, felt sick. Hailey’s mother, Hortencia, struggled to get out of bed, while her grandmother, Pompella, started coughing.

Except for Hailey, all six members of the Moreno family came down with COVID-19, suffering from coughing fits and fevers. Hailey, who was studying for final exams and beginning her final semester at Ellen Ochoa Prep Academy, watched as her mother, grandmother and father were sent to the hospital.

Hailey’s mother slowly recovered, while her father and grandmother remained hospitalized, their health fluctuating for weeks. She struggled to balance schoolwork and attend online classes while tracking their conditions.

Hailey and her sisters video-chatted daily with their father. One of his biggest dreams was for his four daughters to attend college, and one day Hailey was able to tell him that she had been accepted to Cal State L.A. He moved slightly, she recalled, but couldn’t respond.

Pompella, who had helped raise Hailey and her sisters, was struggling too. On Jan. 28, a Thursday, Hailey was taking a nap when around 3 p.m. she woke to the sound of running.

“Everyone was crying,” Hailey said. Her grandmother had died. The family continued to pray for Arturo’s recovery.

But that Saturday, his oxygen level plummeted. In the afternoon, a nurse called and encouraged the family to spend the next hours with Arturo, who remained on a ventilator.

“We would just beg him to breathe,” Hailey recalled, as she and her sisters sobbed on a Zoom call with their father. Arturo Moreno died during the early hours on Sunday, three days after his mother.

These days, Hailey experiences intense sadness when she logs into Zoom classes because it was how she last spoke to her father. Sometimes, she expects to see him on the screen. Any time she begins to feel distracted in class, Hailey said, she remembers January, when her father and grandmother were still alive.

She and her sisters have become closer than ever, rallying around their mother as they try to find a new routine. She also is trying to look to the future. She was accepted to UC Riverside, which she will attend in the fall.

“It’s hard. You see other kids your age ... you hear from them, and teachers, and it’s just, their lives seem so normal,” she said. “It’s not. Nothing is normal.”

Mental health counselors like Jacqueline Felix faced a flood of referrals when school resumed this semester.

The district created group grief sessions out of need. Felix’s middle school students are often in a state of disbelief, she said, and some harbor intense anxiousness about the coronavirus.

“They know that this is a global pandemic and they know they’re not the only ones,” she said.

Often, schools will offer grief counseling following a death of a student, employee or family member. This year, it has been a year-round service.

The way children process grief varies by age. Elementary school children are quick to remember how a grandparent played with them, but find it difficult to grasp the finality of death, Felix said. Older adolescents have an understanding of the aftermath of unexpected tragedies.

Recently, a sense of relief and optimism has entered the grief group sessions, Felix said. Some of the students’ parents have received a vaccine for COVID-19.

“That provides hope, that things will be OK.”

COVID-19 crept into the home of Monica Green, a third-grade teacher at the district’s Rivera Elementary School, on Dec. 12.

Her family had been cautious. Green taught from home. Her husband, Victor, tried to stay safe at the printing press company where he continued to work.

But in December, someone at Victor’s workplace exhibited COVID-19 symptoms, yet he continued to work, Monica said. Then Victor began experiencing chills. One week later, everyone in the household was sick; Victor was rushed to an emergency room.

“It was like a nightmare,” Monica recalled. Her family prayed in the hospital parking lot for him. They had met when she was 13 and he was 16 through their church choir in Pico Rivera, their hometown. He loved to play the guitar.

On Jan. 1, Victor, 57, died. She took six weeks off from teaching.

Lilia Carreon, president of the El Rancho Federation of Teachers, has known the Greens since their El Rancho High days. There are other stories like Monica’s, Carreon said. But without the physical community of campus, others have gone unheard.

“How many more people had a loss and I don’t know?” Carreon said. “That’s probably one of the biggest issues. You don’t know, really, what’s going on.”

Monica Green said she was afraid to return to teaching, worried she might break down in tears. Instead, she said, she found comfort in the easygoing nature of her third-graders.

On her first day back, they held up signs during the virtual class that read “Welcome back” and “We missed you.”

Compounding pandemic losses, the district has been shaken by the deaths of two popular El Rancho High staff members.

Susanne Perea, a clerk in the school’s College and Career Center, often guided students page by page through the complex application for federal student aid. A district employee for 25 years, she petitioned her union to create a scholarship that would cover the costs of college essentials such as mini-fridges and textbooks. A yearbook profile read, “Susie’s got your back!”

Perea died suddenly in April 2020 early in the pandemic, soon after schools closed. It remains unclear whether her death was COVID-19-related. The union renamed the scholarship she founded the Susanne Perea Scholarship after an alumnus donated in her honor.

Five months later, Larry Patino, a baseball coach at El Rancho High, died suddenly from leukemia.

Patino, a homegrown Pico Riveran, had been a beloved figure in the community, particularly when it came to youth sports. For more than 20 years, he coached club baseball and high school teams, his daughter Mina Patino said. He had a rough exterior — his arms were covered in tattoos and he worked campus security at El Rancho High — but to his family, Mina said, he was a “big teddy bear.”

In September, Patino, 47, who appeared exhausted and constantly dehydrated, went to a doctor. Less than 12 hours later, he died.

“Right when it happened, people were calling his phone, saying, ‘This isn’t real,’” Mina recalled. Even with campus closed, members of the baseball team set up a memorial with candles and posters at the school. Today, many wear jerseys bearing his number, 11.

Esparza is feeling more hopeful these days.

Sports training and games have returned, the district’s three high schools will have a combined prom, and 2021 seniors will walk at graduation, with guests present.

But come summer, mental health counselors, who usually take time off, will continue their work with regular check-ins on students. The district will conduct “mini health screenings” for each student.

Said Esparza: “We have to start to move the pendulum back to what normalcy looks like now.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.