SAN DIEGO — Duncan McFetridge says he frequently consults with his “political advisors” at his rural outpost in Descanso — a cast that includes an aged donkey, a retired show horse, nine cats and a massive pit bull named Brutus. And don’t forget the Guinea hens.

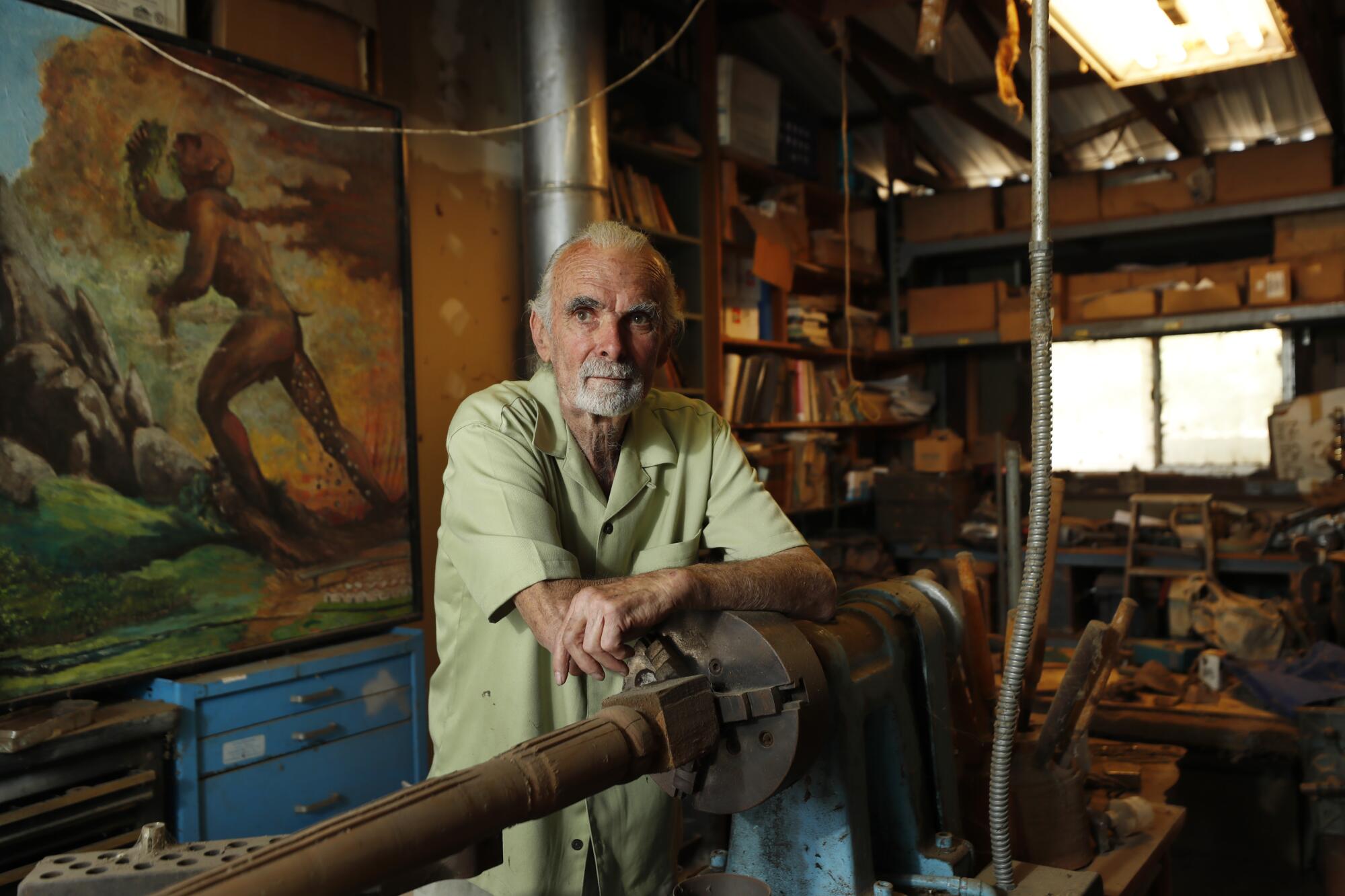

“I’m not protecting nature,” says the 80-year-old. “Nature is protecting me.”

McFetridge has spent the past three decades fighting to preserve San Diego’s wildlands, cashing in his savings and mortgaging his home to pay for campaigns and lawsuits against backcountry development.

Opponents and supporters alike have dubbed him crazy, a description he embraces with oracular poise, while adding with a smile that he’s also “poverty stricken.”

Now after years of ascetic devotion, San Diego’s most quirky eco-warrior may be winning the battle for hearts and minds.

Recent elections have ushered in a wave of civic leaders who are increasingly demanding a shift away from automobile-centric planning that sprawls into the rural countryside. Politicians instead have set their sights on the type of dense, urban housing and high-speed transit long championed by McFetridge.

San Diego’s environmental movement has significantly benefited from his “uncompromising vision,” said Murtaza Baxamusa, who’s collaborated with McFetridge for years and was recently hired by the county to oversee development of a plan to zero out regionwide greenhouse emission by 2035.

“He was considered crazy, and now look,” Baxamusa said. “The arc of the universe bends toward justice.”

Perhaps it’s not surprising that the spry octogenarian is not ready to claim victory.

Eating lunch at his rustic home, he sips a glass of crystal-clear well water. His eyes narrow, framed by bushy brows still clinging to shades of his once-black hair.

“Those are words, and they’re good,” he says of plans to force new housing developments into the urban core. “I want to see action.”

The wander years

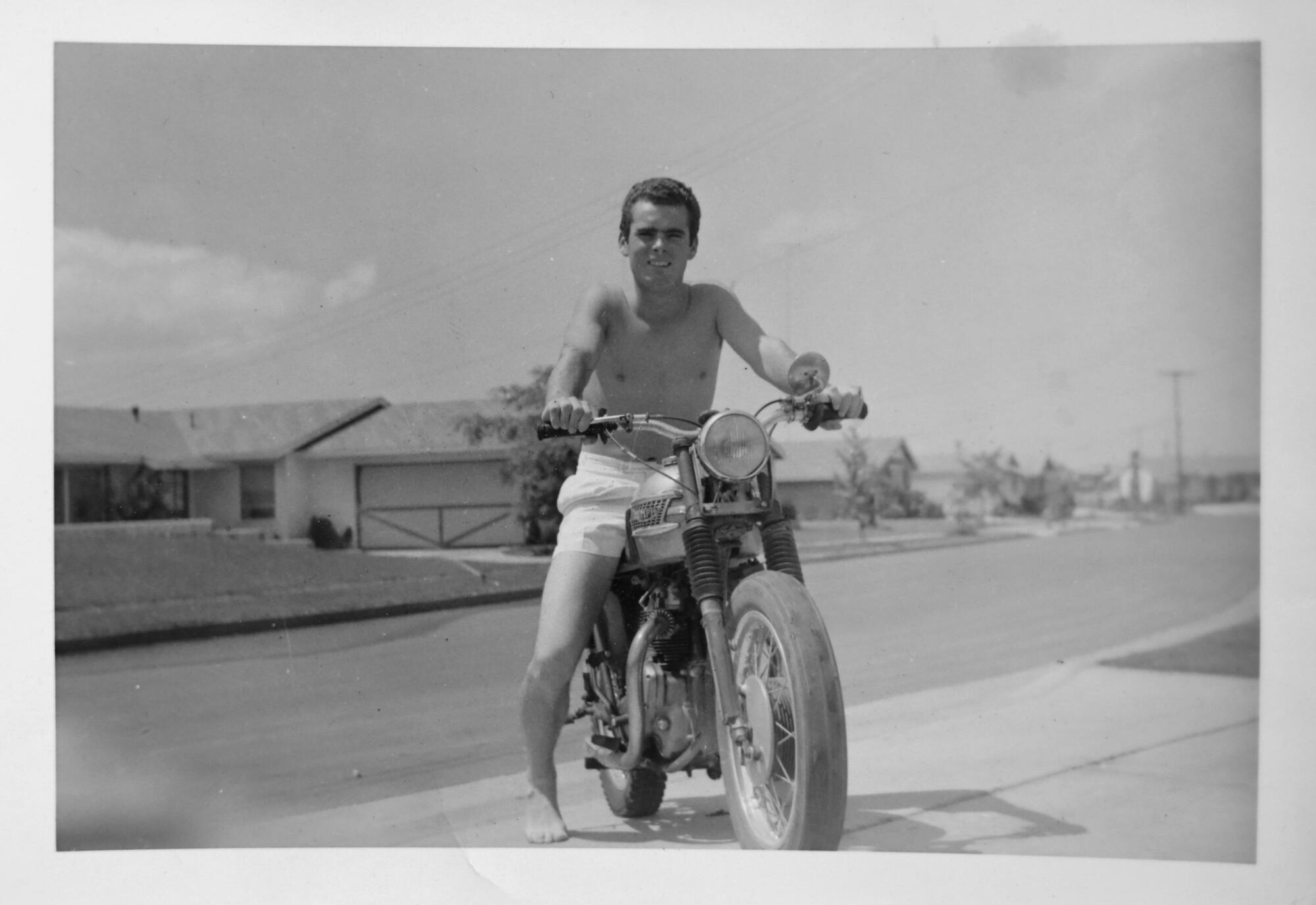

McFetridge was born in 1940 at Scripps Mercy Hospital in Hillcrest. His parents divorced shortly after, and he moved with his mother, younger sister and older brother to Encinitas, where they lived with his grandparents on a small farm that had ducks, chickens, pigs, goats and horses.

“I tried to make pets out of all animals,” he said, showing off a photo of a wild bird sitting on his shoulder. “I have a feeling I was a little different.”

His mother remarried, and the family settled in Ojai, where McFetridge graduated from high school. Shortly after, he moved back to San Diego to work with his grandfather in construction.

In a twist of fate, McFetridge helped build the freeway system he would come to despise.

With the money from his construction job, he backpacked around Europe. He got into a car accident in Bulgaria and woke up in the hospital facing a hefty fine for driving without insurance. His family wired him money, and after about six months of legal proceedings, he made it back to the states.

He went back to work in construction to pay off the debt before taking off again, this time for a study abroad program at the University of Madrid. He hitchhiked to New Jersey in January, thinking he could earn passage to Spain by working on a freighter ship. But the shortcomings of his plan soon became clear.

“It was absolutely freezing, and I’m walking the harbor,” he said. “Everyone said, ‘Kid, you’re about 100 years behind the times.’”

But he eventually found a Swedish ship captain that was amenable to McFetridge’s anachronistic approach. He got onboard and started the grueling work of chipping paint that would be his lot for the next three weeks.

After another European escapade involving stops in Pamplona, Paris and again Bulgaria, McFetridge returned to the states in 1963. He was drafted during the Vietnam War, serving for two years as a medic at a military hospital in Fort Lewis, Wash.

Using the GI Bill, he attended UC Santa Barbara to study ancient Greek philosophy. Eventually, he moved back to San Diego, where he worked as an orderly at a drug rehabilitation clinic while finishing his bachelor’s degree at San Diego State.

An activist is born

McFetridge’s introduction to activism came in the 1990s, when developers started eyeing property around Descanso, largely ranchlands in the Cleveland National Forest. Most notably, a 128-home development was proposed for the 714-acre Roberts Ranch, which straddled Interstate 8 at Highway 79.

McFetridge started to worry the project could have ripple efforts akin to development in Los Angeles. “We are literally talking about the death of the Cleveland National Forest,” he said at the time.

By 1992, McFetridge had formed a grassroots nonprofit named Save Our Forest and Ranchlands and launched an anti-development campaign. The group blocked a county zoning update in court that would have allowed the project. Eventually, the U.S. Forest Service purchased the land.

The next year, McFetridge spearheaded a successful ballot measure called the Forest Conservation Initiative. He took a mortgage on his home to pay for the signature drive. The citizen’s initiative prevented backcountry development in the Cleveland forest by changing the minimum lot size on private lands outside county towns from four to 40 acres.

Jack Shu was working as the superintendent of the Cuyamaca Rancho State Park, just up the road from Descanso. He ran into McFetridge one day passing out fliers near the I-8 freeway exit. In short order, he was attending community meetings organized by McFetridge.

“I thought, in a good way, he was crazy,” Shu said. “He was so sure he had to do the right thing, he didn’t care when advisors and friends said, ‘Duncan, don’t do that. You might lose lots of money.’”

McFetridge formed the nonprofit Cleveland National Forest Foundation in 1995, with Shu as the president of the board. Shu resigned from that post after recently being elected to the La Mesa City Council and subsequently appointed to the board of the San Diego Assn. of Governments.

The agency, once a target of McFetridge’s lawsuits, has made a political U-turn in recent years. As the region’s top transportation planning agency, SANDAG is developing a high-speed transit system forged around promoting urban density.

McFetridge’s unflinching persistence has proved surprisingly powerful, Shu said. “That was a lesson for so many of us who were involved with environmental and planning issues. He kept us on the right direction.”

Many lawsuits

McFetridge has also had his setbacks. He failed at the ballot box in 1998 and 2004 to establish urban growth boundaries in the county.

Still, his victories over land use in San Diego County are numerous, from blocking an RV park in Descanso to stopping a housing project that would have cut off the last mountain-lion corridors connecting the Santa Rosa Mountain Range in Orange County and Palomar Mountain in San Diego County.

“I think Duncan has a lot to do with holding off San Diego from turning into L.A.,” said Jana Clark, an environmental advocate who has worked closely with McFetridge for years. “Without him, we’d have so many projects in the backcountry.”

In 2011, he sued SANDAG through the Cleveland National Forest Foundation, arguing the agency was focusing too much on freeway building and not enough on rail. Specifically, the lawsuit, which was joined by the Center for Biological Diversity, the Sierra Club and then-state Atty. Gen. Kamala Harris, contended that SANDAG’s long-term planning failed to lay out a strategy for meeting state targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, among other things.

Then in 2013, his foundation sued Caltrans over its planned expansion of Interstate 5 from La Jolla to Camp Pendleton.

McFetridge eventually prevailed against SANDAG in trial and appellate courts, with an appeal to the state Supreme Court only partially overturning those victories in 2017. The case set a precedent for metropolitan planning organization across the state when it comes to measuring health impacts as well as ways to rein in greenhouse gases.

He reached a settlement agreement a few years ago with Caltrans in which the agency agreed to study the feasibility of a tunnel through Miramar Hill that would speed up coastal rail service.

For all his activism, McFetridge says he’s worried more about the planet. The topics of species extinction and climate change are never far from his lips.

“Nature is in charge,” he warned. “Really, I’m serious.”

Smith writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.