‘Go for Broke’ Japanese American veterans get a postage stamp marking WWII service

- Share via

At 16, Don Miyada was wrenched from his family’s farm near Laguna Beach and sent to a prison camp in Arizona.

Two years later, he was drafted into the U.S. Army, ready to give his life for the country that stole his home.

Now, Miyada and the 30,000 or so other Japanese Americans who served in World War II are being honored with a postage stamp.

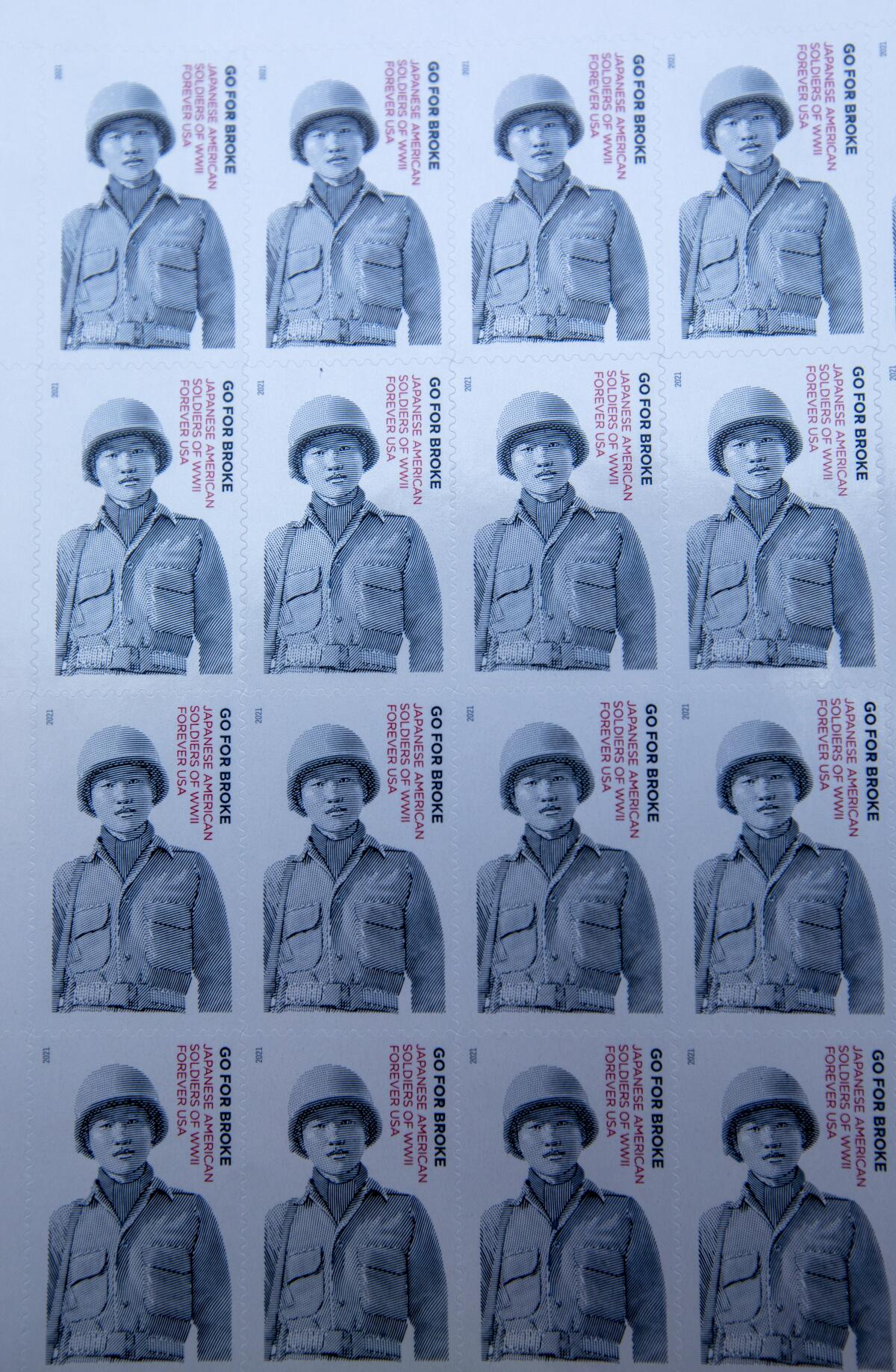

On the stamp, a soldier stands in uniform and helmet with a serious expression on his face, the motto “Go for Broke” emblazoned vertically.

The image is taken from a 1944 photo of U.S. Army Pfc. Shiroku “Whitey” Yamamoto of Hawaii, a member of the Japanese American 442nd Regimental Combat Team whose heroics in Europe earned them thousands of Purple Hearts, awarded to soldiers wounded in battle.

“Go for Broke” meant they were putting it all on the line, both to fight the Germans and to demonstrate their patriotism as many of their families and friends remained in the prison camps for alleged disloyalty to the country.

“In those days, we had very little chance to work outside of produce markets and the farms,” said Miyada, 96, at a ceremony unveiling the stamp at the Japanese American National Museum on Friday. “But the war changed all our lives. War is hell, but it leaves lessons.”

Miyada served in the 100th Infantry Battalion, another all-Japanese American fighting unit that was eventually absorbed into the 442nd.

The exploits of the 442nd members and other Japanese American soldiers, including those who used their Japanese language skills to collect intelligence on the enemy in the Pacific, have gained increasing recognition over the years.

But it took a determined campaign, beginning in 2005, to make the stamp a reality.

To mark the 75th anniversary of the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, a group of California activists called on the U.S. government to honor them with a postage stamp.

Fusa Takahashi and Chiz Ohira both married men who served in World War II. Aiko O. King had been a civilian nurse for the U.S. Army.

All three women spent years in the prison camps where the U.S. government sent Japanese Americans during the war.

Wayne Osaka, who has relatives who served in the war, joined the “Stamp Our Story” effort the following year.

They collected endorsements from lawmakers, governors and mayors. They won support from people in the areas of France liberated by the “Go for Broke” troops.

They sent the U.S. Postal Service 10,000 handwritten signatures and 10,000 online signatures.

In 2009, postal officials told them that stamps were not allowed to honor individual military units.

Years of silence ensued, until last November, when the Postal Service announced the “Go for Broke” stamp, along with stamps honoring Missouri statehood and the nuclear physicist Chien-Shiung Wu.

Takahashi and King are now in their 90s. Ohira died during the campaign’s 15-year length.

In a statement, U.S. Postal Service officials said they were “proud to honor the bravery and sacrifice of Japanese American soldiers during World War II. They lived up to their motto with legendary acts of heroism,” and their “spirit and perseverance continue to live on in generations of Japanese Americans ever since.”

To Yoshio Nakamura, an ammunition carrier in the 442nd, the stamp’s debut is timely, considering the rise in anti-Asian attacks during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Not everyone knows of the Japanese American effort in the war, when, actually, we have helped the U.S. so much through the years,” said the Whittier resident, 95, who received a Bronze Star.

Kerri Krueger, Fusa Takahashi’s granddaughter, said her grandmother taught her to be proud of her heritage and to know what Japanese Americans had suffered and overcome.

Her grandfather, Kazuo Takahashi, was drafted into the U.S. Army from a Utah prison camp in 1943. He joined the Military Intelligence Service, which employed Japanese Americans as translators to pore over documents, interrogate prisoners and intercept messages from the Japanese military.

“She wants the generations to try to understand what Asian Americans have been through, how they have progressed so far,” Krueger, 32, said of her grandmother.

The 55-cent stamp, designed by Antonio Alcalá, will always be good for up to 1 ounce of first-class mail.

Lynn Franklin, the Takahashis’ daughter, said the stamp represented “how much my father and all the men and women were Americans, in every sense, and how they were willing to give up everything for America.”

At the same time, many of the soldiers were fluent in Japanese and understood Japanese culture — a tremendous advantage for the American side in the Pacific theater.

Kazuo Takahashi, who died in 1977, rarely spoke about the war. But his wife always remembered what he did and wanted the world to know about it.

“These people translated millions of documents. They did a lot of counterintelligence. They showed their patriotism at every turn,” said Franklin, 64. “That’s why my mom refused to give up in the struggle to get a stamp.... She intended to showcase courage.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.