Runaway animals are as L.A. as car chases. Here’s why they make headlines

Thousands of us watched and cheered the Pico Rivera 40 — the cows who broke out of a slaughterhouse last month, and briefly roamed the streets as free cattle at last. Some of us may even, without irony, have been eating a burger while we watched.

Two of the 40 reached safety, and they alone were spared their fellow escapees’ end. As the company chairman’s statement read bluntly, “I am in the meat business. The animals were harvested” — meaning slaughtered. The surviving cows were sent to a farm sanctuary in Acton on what I will call a rescue scholarship from songwriter Diane Warren.

For the record:

3:17 p.m. July 24, 2021A previous version of this report said one cow was rescued out of the 40 that escaped from a Pico Rivera slaughterhouse. A second cow found eight days after the breakout was also sent to a farm sanctuary.

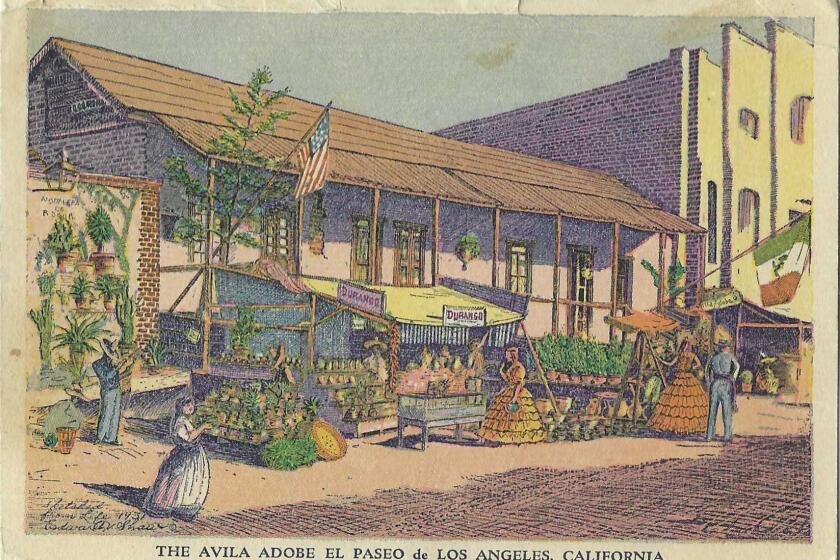

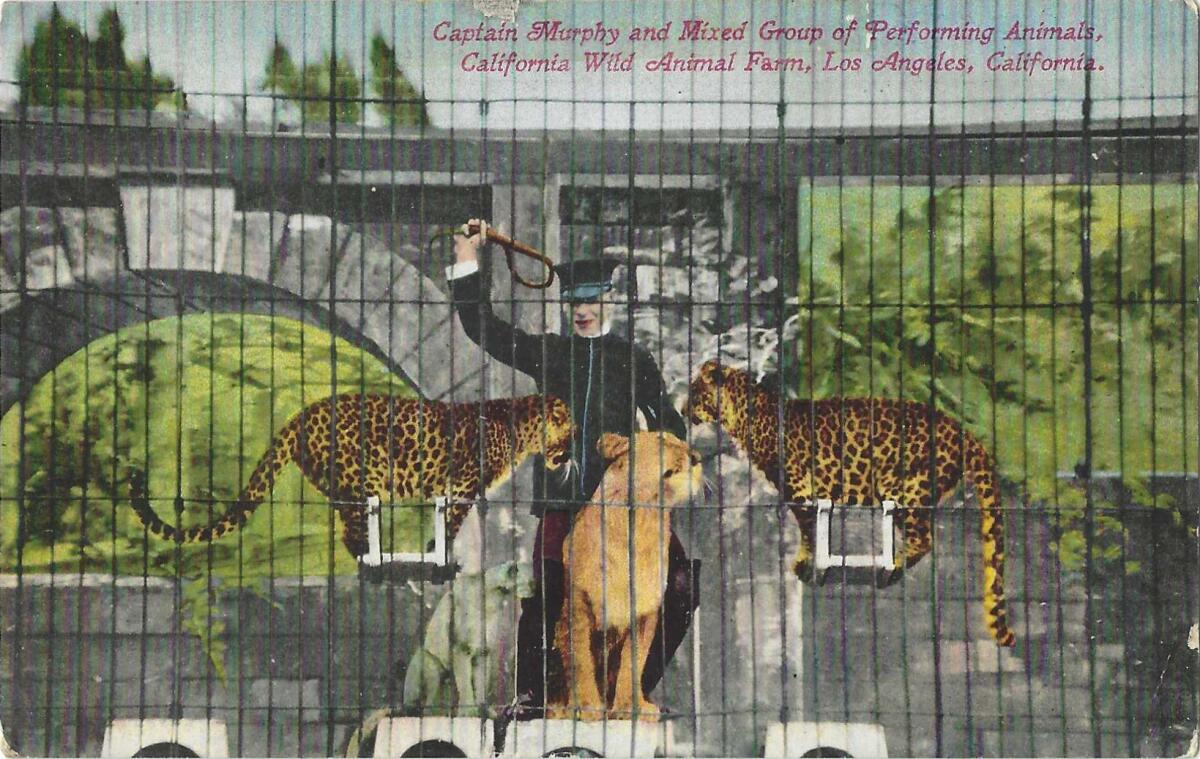

Since The Times began recording such stories well over a hundred years ago, animals domestic and exotic have gotten loose and been on the loose in L.A. We’ve had more than our share of these bust-outs, because so many critters have been kept here in zoos that doubled as casting agencies for moviemakers.

Over those years, the tone in the stories has changed because our reactions have changed, from headlines like “Circus Beasts Turn Killers After Escape” to rooting for the runaways.

In 1918, five Barnes Circus elephants were frightened by a stray dog, burst out of the training ring in Venice and, trumpeting their liberation, headed down Mildred Avenue to Washington Boulevard in a pouring rain before they were recaptured and put back in chains. What The Times called the “lumbering brutes” and “maddened beasts” didn’t hurt anyone.

To use the Pico Rivera cows as an example: In 1917, seven Texas longhorns escaped from a slaughterhouse north of downtown and managed to make it to the business district, where, as The Times moralized sternly, “One by one, they were shot and killed. They had their fling and paid for it.” A cop trying to shoot one of them missed and wounded a traveling salesman in the leg. Three steers busted up an Indian Motorcycle salesroom, a momentary triumph of four legs over two wheels. Today, people would be taking selfies like it was Pamplona on the Pacific.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

Our changes of attitude aren’t because we are anthropomorphizing our own longing onto them; every creature, from the minutest to the massive, wants to escape from pain and death.

Naturally some of it is entertainment value; animals escaping from being victims of captivity and outwitting our species are to be admired. Technology allows TV news to put us right there in the moment, so we can watch these escapes live, like a sports event, and cheer for the four-legged team.

In the spring of 2005, an illegally owned alligator named Reggie was furtively dumped into Lake Machado in Harbor City by two buddies — one of them an ex-LAPD cop — who couldn’t handle him any more. Some exotics, like certain snakes, can be kept legally; alligators are not among them. At the buddies’ houses, only a mile apart, investigators found three young alligators, four piranhas, a rattlesnake, three desert tortoises, a scorpion, and two snapping turtles.

For about a year and a half, Reggie did a PR striptease; he let himself be seen, then submerged again.

Astoundingly, the hunt for Reggie netted another, smaller alligator. Reggie himself was captured in May 2007, to the dismay of his fans. A Wilmington longshoreman named Danny Gutierrez said as much. “I’m disappointed. My wife called me at work, and I got on the company radio and announced, ‘Poor Reggie’s been captured.’ ”

By then, he measured in at seven and a half feet, having grown at least a foot during his liberty, and was taken off to the L.A. Zoo, where he briefly escaped from his enclosure a few months later. You can’t keep a good saurian down.

L.A. was definitely Team Reggie. He was a merchandiser’s dream, selling hats, pins, and T-shirts. Two children’s book recounted his adventures sympathetically. If Reggie had been playing peek-a-boo a hundred years ago, the clamor would probably have been for a handbag made of real Reggie. If it happened today, there’d be a Gator Cam 24/7, and a Facebook page. (He does have his own Wikipedia entry.)

You can determine L.A.’s seasons by our plant life. For example, right now, it’s jacaranda-blooms-stuck-to-your-windshield season. And to understand the Southern California landscape you see, you have to realize that, like you, it is probably not from around here.

As I wrote back then, Reggie embodied our outlaw-yearning selves. We like it that the ransom-hijacker D.B. Cooper may have gotten away with it. As life gets more urbanized and structured and self-documented, kicking over the traces to a mythologized rogue freedom can look pretty enticing.

That hasn’t changed. What has changed is that animal abuse is no longer opaque. The grotesque video spectacles of circus animal training, of cruelty in slaughterhouses, have blown up the illusion of what’s behind the spangly circus stunts and the fences and walls of slaughterhouses and butcher shops painted with happy pigs and cows.

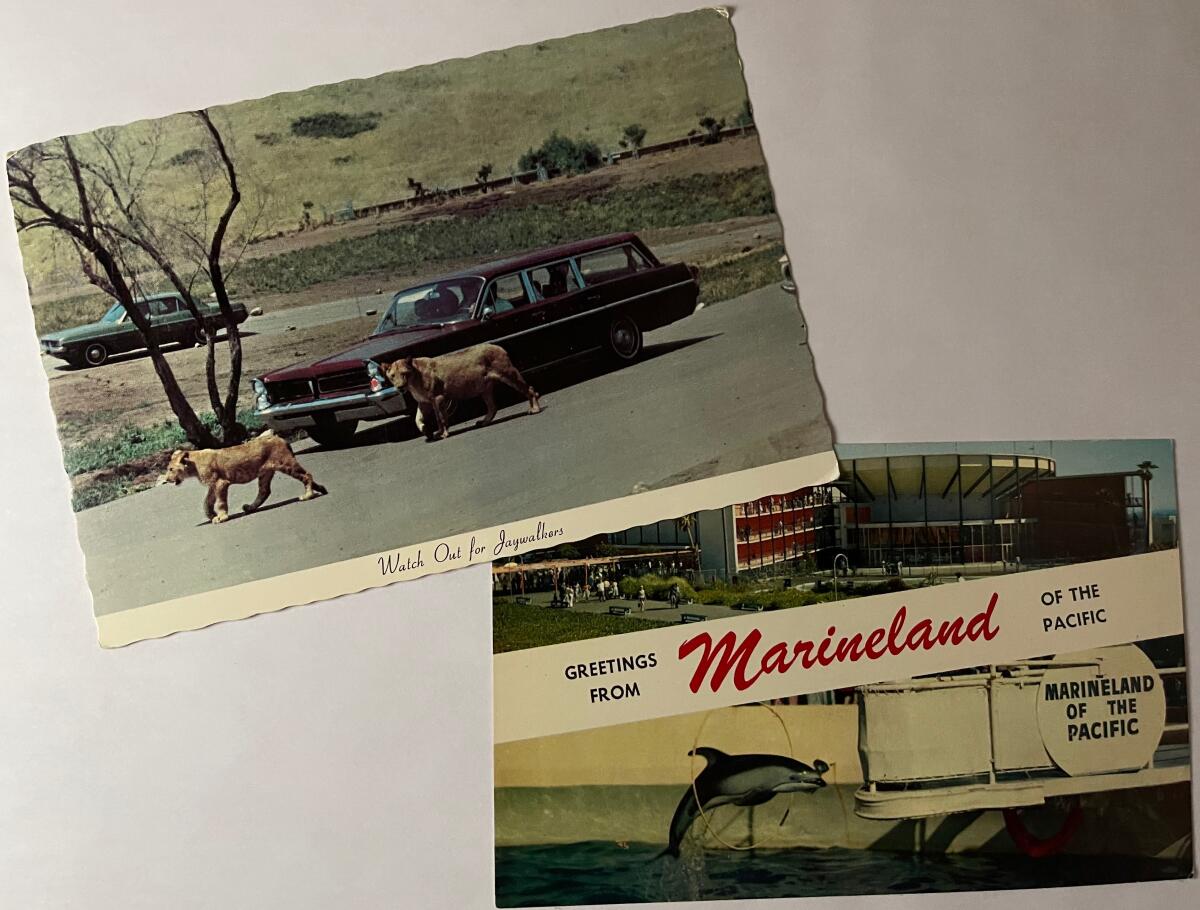

In November 1961, in Newport Harbor, a solitary orca was swimming alone when a Marineland of the Pacific team closed in on her; no killer whale had been caught alive before.

“Wanda” tried for hours to get away, and as the Long Beach Independent-Press Telegram reported, “When she broke out, cheers rose from thousands lining the banks. Every time a lookout on the bowsprit missed her snout with his lasso, or broke his line, she got cheers.” Trapped at last in a web of nets, the exhausted 17-foot orca was trucked to Marineland, on the Palos Verdes Peninsula, where, two days later, Wanda effectively killed herself, swimming frantically within and even into the walls of the small oval tank. Marineland closed in 1987, partly because people were learning what confinement really meant to these sea marvels.

Then there was Selig Zoo, whose owner was a showman and West Coast movie pioneer. Every few years, a Selig Zoo inmate would make a getaway and make headlines.

In 1926, it was an escaped monkey who bit a 22-year-old waitress at the zoo’s restaurant. Her hair went gray with the shock of it, she said, and she had ceaseless nightmares about simians. Five years earlier, it was a movie lion named Llewellyn, who was shot after he found a way out.

And in 1915, a monkey dressed nattily in men’s clothes — for which I could find no explanation, which was very shoddy journalism indeed — found an unlatched cage door and went walkabout. He wandered into the Lincoln High School gym, and was last seen walking along Broadway, north of downtown, appearing to some passersby to be nothing more noteworthy than “a diminutive man with a monkey’s cap on.”

Some creatures never get recaptured and become part of the landscape. The bison herd that makes Catalina Island picturesque did not swim there. They were imported for the 1925 movie “The Vanishing American.” The book “To Save the Wild Bison” recounts that when the cast and crew left, they left the bison behind. At one point 600 bison, bred for life on enormous plains, overran the 76-square-mile island, and it took some time, and some fancy birth control, to get the population in hand.

If your timing is right — which is to say you didn’t just get your car washed — you’ll enjoy the sight and raucous sound of the flocks of parrots gone wild, chiefly in Pasadena and the west San Gabriel Valley. The parrots share the trees with parakeets, cockatoos, and exotics like India’s red-whiskered bulbul.

Urban tales abound of how they came to be feral: that firemen released birds from their cages in a fire at a pet store, that birds got away from the aviary of the Busch mansion in Pasadena, and that your messy, loud pet parakeet “accidentally” got away after the millionth time your parents cleaned the cage when you didn’t do it.

Yet ornithologist Kimball Garrett, the Birdman of the L.A. County Natural History Museum, told me that most of our feral flocks are completely naturalized descendants of the exotic bird trade, once legal but now prohibited. Smugglers still bring in banned birds anyway, and when they’re caught, they let the evidence escape.

Native American settlements were first, and then the rancho system -- Spanish then Mexican land grants throughout California -- were built atop and near those settlements and still shape our geography and place names.

The saddest escapee story is Bubbles’ — not Michael Jackson’s chimp, but an Orange County hippopotamus.

From 1970 to 1984, in the sere hills of Irvine, people paid admission to drive their cars through a wild animal park where, “Jurassic Park” fashion, things could go wrong. Monkeys sometimes swarmed the cars and pulled off bits and pieces. In 1983, Misty the elephant broke loose, killed her handler, charged at some medics and stomped off toward the 405 Freeway, which is a mess in the best of times. The sight of a free-range elephant shut it down completely, until Misty could be sedated and brought back to the park.

In early 1978, Bubbles, a two-ton hippo, and her 800-pound daughter managed to smash their way out of their compound. They were hustled back inside but soon did it again, and moseyed back on their own. Bubbles was put in solitary, but she “scaled” — the park’s word for it — a 4 ½-foot wall, bulled down a fence and was gone again.

She somehow crossed busy Laguna Canyon Road unscathed and reach a pond about two miles from the park. Her fans put up a “caution – hippo crossing” sign. For 19 days, she evaded the men who came with poles and nets and ropes, and a helicopter that thwapped its rotor blades at the water to roust her.

Bubbles made the national news. She made Johnny Carson’s monologue. She made fools of her pursuers. She made T-shirt makers happy.

Then, one night, she left the pond to forage, and a ranger hit her with tranquilizer darts. Bubbles fell head-down on a slope and died of what was called “respiratory embarrassment,” unable to breathe in the downslope position.

“Death Comes to Bubbles” was The Times’ semi-solemn headline in election-night-sized type. Bubbles’ post-mortem found she was halfway along in another pregnancy. Her skull and bones rest with the Natural History Museum.

I’ve kept the best and strangest wanderers for last: the camels.

This is a story bound up in legend as well as fact, but there is plenty of fact. For some while in the mid-1800s, U.S. military men and even the secretary of war, Jefferson Davis — future president of the breakaway Confederacy — thought that camels might be as useful in the deserts of the American Southwest as they were in the deserts of the Middle East, as indefatigable carriers of goods and mail, and with military potential. After all, the U.S. Marines had used camels in 1805, in the war against the Barbary pirates on those “shores of Tripoli.”

In 1855, Davis wheedled about $20,000 out of Congress, enough for a trip to the Mideast to buy 30-some camels and dromedaries and hire “cameleers.” They arrived by ship on the Texas coast, and came across New Mexico and Arizona and into California.

The camels could certainly navigate the deserts on little water, but they tended to wander off from camp. Mule-skinners found they couldn’t handle camels’ pure cussedness the way they managed mules. They frightened horses and soldiers.

But they had a convert in Edward Fitzgerald Beale, a military man, frontier visionary, adventurer and California pioneer who was commissioned to use the camels as he surveyed new desert routes. He found them to be “economical and noble brute[s].”

On a fall afternoon in 1857, on his way to Ft. Tejon in the north, Beale brought the camels through town, and that of course brought L.A. to a momentary standstill. The camels, it turned out, would be back for the Civil War. One was memorably photographed at the Drum Barracks in Wilmington. In 1861, some were corralled downtown, on the future site of the L.A. Times’ Times Mirror Square.

The most renowned of the original military camel handlers was “Hi Jolly,” a corruption of the name Hadji Ali, who worked for the Army for years and released his own camels into the Arizona desert, not far from his much-visited gravesite in Quartzsite. The other was “Greek George,” George Caralambo, who is buried in a Whittier cemetery. Caralambo took U.S. citizenship and the name George Allen, living in Hollywood and dying near the San Gabriel Mission — not as a suicide after killing a man in New Mexico, as some tall tales went.

Hi Jolly is a character in two movies about the “camel corps,” neither of them very good: a 1954 B-western called “Southwest Passage,” and a 1976 slapstick comedy named “Hawmps!”

The Civil War put an end to the camel experiment. Jefferson Davis finally did get his military camel — at the battle of Vicksburg, where one, named Douglas, serving with a Mississippi regiment, was shot and killed. He was buried in a Confederate soldiers’ cemetery there, or at least there’s a headstone; hand-digging a grave for a camel would have been a monumental undertaking.

Over the years, the camels escaped, were sold off to circuses and to mines, or turned loose. They roamed the deserts of Nevada, Arizona and California. In the 1880s, a little boy named Douglas MacArthur, the future general, saw one outside the military garrison his father commanded in New Mexico.

“Topsy” was rumored to be the last Army camel when she died in 1934 in the Griffith Park Zoo, but that would have put her in her 80s, an uncommonly long life for a dromedary.

So much for confirmed sightings. Unconfirmed sightings went on into the 1930s.

Now here is where you sit in the dark and hold a lighted flashlight under your chin and tell this in spooky campfire fashion:

For years, for decades, people said they saw not just rogue camels in the Southwestern desert, but phantom camels too. Sometimes it was a ghostly caravan, and sometimes, it was a solitary camel trotting along at twilight — and sitting upright on his hump … a grinning human skeleton.

L.A. is a place like no other. You’ve got questions. Patt Morrison probably has answers and can definitely find out.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.