Staffing shortages, exhaustion, family vacations temper big summer-school hopes

- Share via

The message to schools from top brass, including Gov. Gavin Newsom and U.S. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona, was clear: Summer programs in 2021 should be robust. They should reach as many students as possible. And above all else, they should be fun.

To make it all happen, California school districts received a collective $4.6 billion from the state in early March to address learning gaps widened by the pandemic and to prepare students mentally and emotionally for their return to campuses in the fall.

But despite the funding surge that has allowed a vast majority of California school districts to open this summer, the size and scope of many programs have been limited by teacher and staffing shortages, the inability of districts to ramp up programs fast enough, and families’ desire for a break amid ongoing safety concerns.

And several of the region’s largest districts, including Los Angeles Unified, have had less attendance than hoped for, even with unprecedented resources.

“So many districts hadn’t done this before and were really scrambling to figure out how to spend the money, where to hire the staff,” said Jennifer Peck, president of Partnership for Children and Youth, an Oakland-based organization that advocates for extended learning programs for students from underserved communities.

Because of the past dearth of funding, public summer school has long been offered mainly as specialized instruction for students with disabilities, credit recovery for high schoolers, and math and language arts remediation. Relatively few California school districts had the bandwidth or money to offer free enrichment opportunities such as outdoor recreation, visual and performing arts and second-language classes.

Nearly everyone agrees: Remote learning has set back many, if not most, California students. So is summer school the key to getting kids back on track? Maybe not.

But this year, 73% of California school districts planned to provide enrichment classes as of early June, state data show. State officials encouraged schools to partner with community organizations to provide options that would be both fun and academically fortifying.

This year, L.A. Unified and San Diego Unified, the state’s two largest school systems, opened up in-person summer programs to all students.

By July 8 in Los Angeles, about 100,000 students — about 22% of the 465,000 student population — were enrolled in a summer program, according to the district. L.A. Unified partnered with community organizations to offer a diverse array of enrichment courses for K-12 students: sports and nutrition, language study, cartoon drawing and animation, and dance choreography among them.

Despite the district’s efforts to draw in more students with these opportunities, enrollment numbers were similar to 2020, when all summer classes were online. This summer, 41% of attendees were online.

Alison Yoshimoto-Towery, L.A. Unified’s chief academic officer, said families are taking advantage of the ability to travel for the first time since the pandemic hit last year. “The fact that so many families still selected the online option says something,” she said. “I don’t know if it’s safety or convenience.”

Yoshimoto-Towery noted that before the pandemic, K-8 summer enrollment was “extremely small,” so increased participation for those grades — and the funding that allowed for it — is a boon.

The summer school funds, allocated through Assembly Bill 86, can be used through Sept. 30, 2024, for instructional supports throughout the upcoming school year and into next summer. If the money isn’t spent by that time, the state will collect the remainder from districts. L.A. Unified received $401 million out of the $4.6 billion given to California districts.

San Diego Unified saw its summer enrollment jump nearly fivefold from 2019 to2021. The district typically serves 5,000 of its 98,000 students through its summer program, which in the past comprised credit recovery for high schoolers and an “extended school year” for students with special needs. This year, 23,000 students signed up for the district’s expanded offerings for K-12 students, said district spokesman Andrew Sharp.

Parents also support requiring COVID-19 vaccinations for eligible students.

“It’s a sea change for us,” Sharp said. The state funding “gave us the opportunity to build programs we’ve always wanted to build.”

San Diego Unified is offering enrichment opportunities through partnerships with community organizations, including the San Diego Zoo, La Jolla Playhouse, Girl Scouts and YMCA, which is hosting a surf camp.

Long Beach Unified School District almost doubled its usual summer school enrollment from 2019 to 2021. However, the district stopped short of offering its Supports, Enrichment & Accelerated Learning program to all K-8 students because of staffing challenges. Students with the highest needs were prioritized, and other families could enroll their children upon request.

“We advertised summer school as a way to ease students into the fall, and we used an exciting array of enrichment courses and extended hours as incentives,” said Christopher Lund, the district’s assistant superintendent of K-8 schools.

The state funding enabled some smaller districts to offer summer school for the first time in years.

Hawthorne School District, which mostly serves K-8 students with the exception of one charter high school, stopped hosting summer school in 2016 because of poor attendance and limited resources. This year, 530 of Hawthorne’s 8,000 students — 89% of whom received free or reduced lunch as of the 2019-20 school year — are enrolled, with 15 on a waitlist, said the district’s director of special projects, Michael Collins. The district could offer programming only to high-needs students because of staffing shortfalls.

Many districts struggled to recruit teachers to work this summer after a grueling year. Palmdale School District, for instance, has a waitlist of 400 students because not enough teachers volunteered. The district’s programs were capped at 805 students.

Candace Craven, Palmdale’s extended learning coordinator, said it “felt terrible” to turn kids away. “But I will say, the teachers who wanted to do it were so excited about getting back in front of their students,” she said.

Some districts incentivized teacher participation with pay bumps — raises made possible through the influx of state funding. Others offered flexibility to their summer staff. Lawndale Elementary School District and Redondo Unified encouraged teachers to develop curriculums they’d most enjoy teaching, while Hawthorne School District let teachers opt for two- and three-week shifts in lieu of the full five.

COVID-19 safety measures also inhibited classroom capacity. Cohorts were limited to 10 to 15 students at many districts, as outlined in agreements with teachers unions.

Some districts’ offerings were further hampered by the time crunch. “When the state funds were allocated in March, we had to write a plan and have the board approve it by June,” said Nadia Hillman, assistant superintendent of educational services at Duarte Unified School District. “There are lots of things we can and want to do, but by the end of the year we had a lot of tired folks.”

Attendance was also curbed by academic exhaustion. Many families just needed a break, district administrators said.

This was the case in Duarte, a mostly Latino community hit hard by the pandemic. Summer school enrollment at Duarte usually hovers around 1,000. This year, 850 enrolled — in part because of staffing shortages but also because many parents chose to keep their kids home.

“They could finally go out and take a vacation,” Hillman said. “And some of our families are still not quite ready to send students to school in person.”

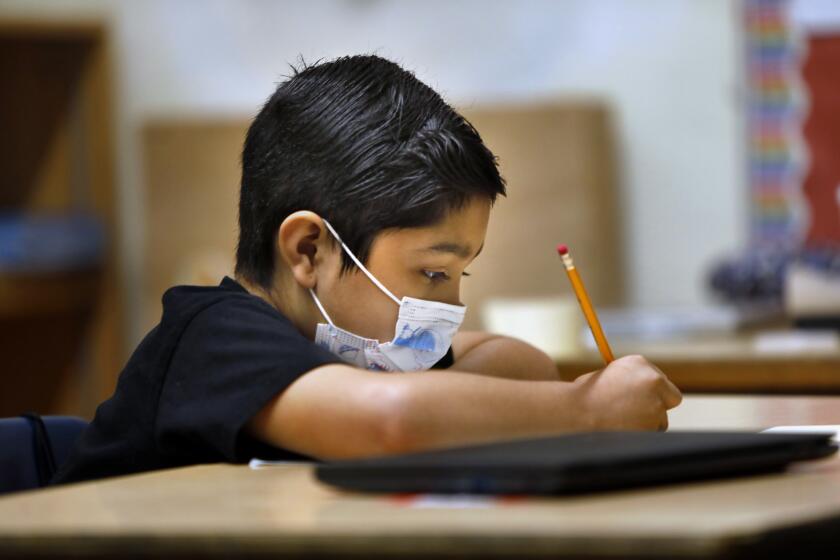

Many parents still opted for summer school in the hopes of catching their children up.

Renee Bailey’s daughter, Cali, will enter first grade at Westwood Charter Elementary without knowing how to read. Online learning did not resonate with Cali; she couldn’t focus and retained little information. The Baldwin Hills mom saw some promise in L.A. Unified’s summer programs, though her expectations weren’t high, given how behind Cali was.

“I felt like it was very important for Cali to learn classroom etiquette, to meet friends and to try to bring her up as much as we possibly can academically,” Bailey said.

After four weeks, Cali hadn’t improved much in her reading, Bailey said. But she’s excited every morning to go to school and see her new friends — a win in its own right.

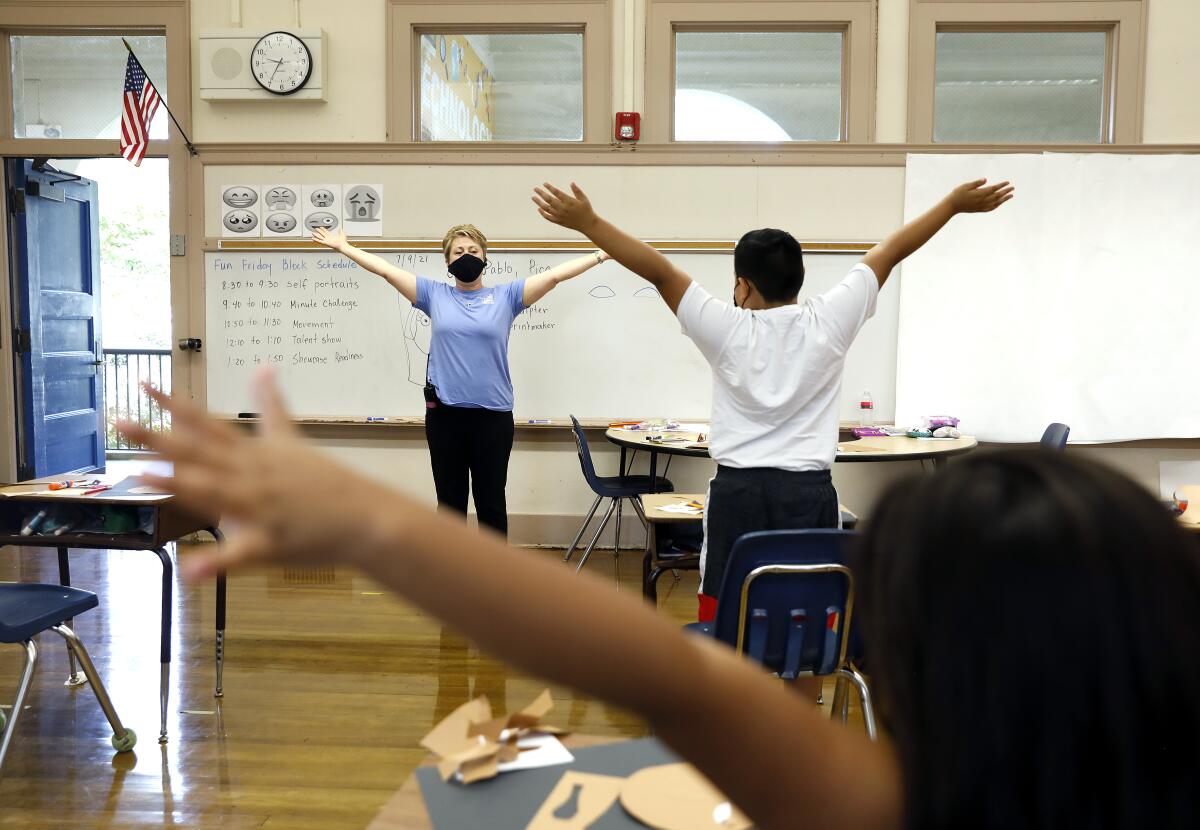

Preparing kids for their return to campus, through low-stress activities with classmates and social-emotional learning exercises, is at the heart of many programs.

At Pasadena Unified School District, K-8 students were immersed daily in activities designed to boost emotional literacy, confidence and communication skills. Students made “feeling flip books” to explore how difficult emotions manifest in their bodies and behaviors and what they can do to cope, and “worry pillows” to squeeze when they’re overwhelmed.

“A lot of the students who’ve come in had a lot of trepidation around being with other people after being isolated for so long,” said program director Maria Toliver. “These activities brought some calm, some softness to the atmosphere and got them into groups, so it won’t be as traumatic once school starts.”

Redondo Beach Unified School District offered two-week “summer bridging institutes” that enabled beleaguered students and teachers to focus on just one subject or activity for a short amount of time. Classes included reading in Spanish, a journalism course for first-graders, and intramural sports and drama.

The district based the program on research that shows student engagement is driven by choice, and the understanding that teachers and students were burned out.

The institutes have been popular. “We had teachers coming out of the woodwork to lead these passion projects,” said Susan Wildes, the district’s assistant superintendent of educational services. More than 1,600 students signed up for at least one class, with many others opting to take multiple. The district usually enrolls about 300 K-8 students in summer school.

“We really wanted to focus on getting kids excited about school restarting, “ Wildes said, “opposed to filling in gaps of what they missed.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.