A summer of terror, heartbreak for those in path of California wildfires. ‘The worst’

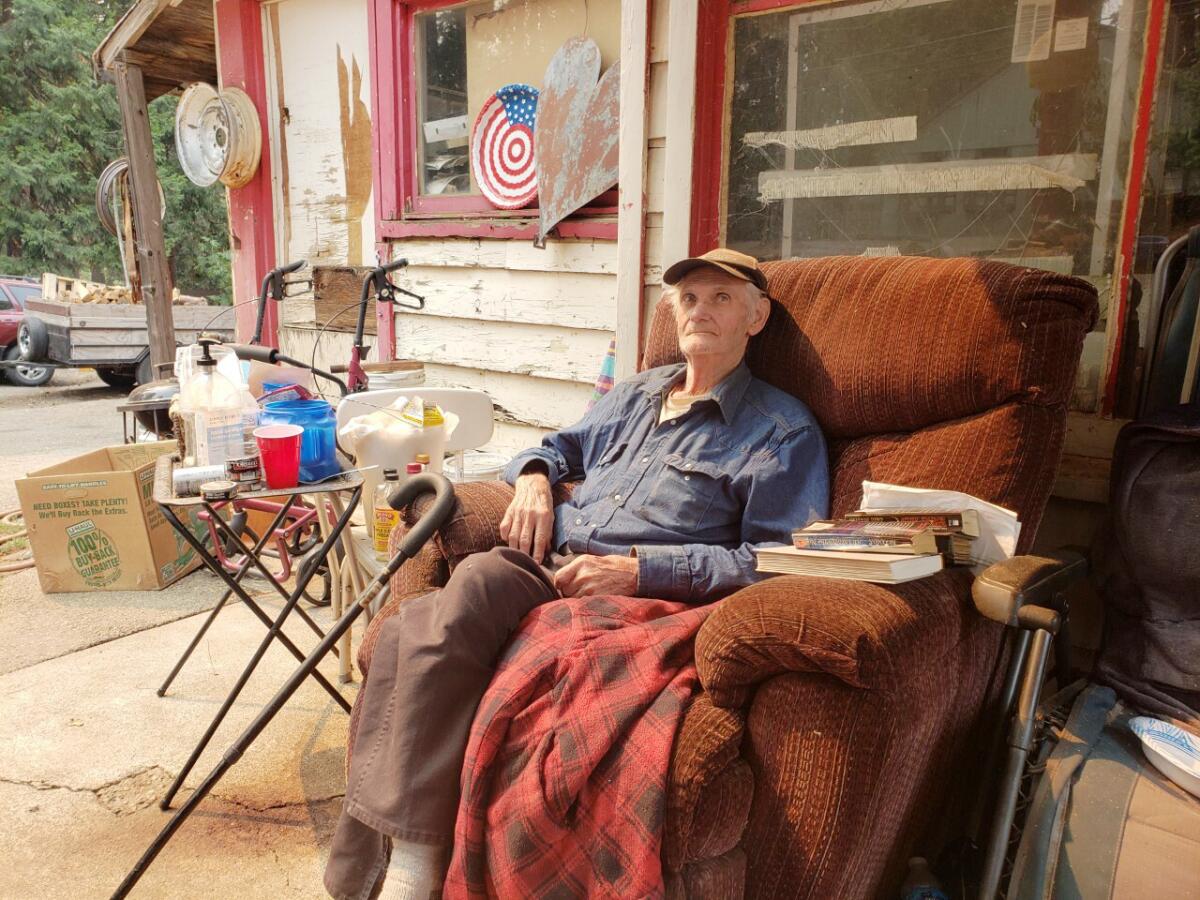

POLLOCK PINES, Calif. — Gordon “Oly” Olson sat on his porch, unfazed, as a light rain of ash fell over his weathered recliner.

At age 82, the Pollock Pines resident is no stranger to wildfire. Seven years ago, he beat flames back from his property, staying up for two days straight and drinking water that had been left out for his pets. Before that, in 1978, the wildfire won a round, burning his forehead and arm and torching the bulldozer he’d been using to fight it.

“Fires are about like the weather,” Olson said, in between spitting plugs of Grizzly fine cut chew and batting at his arm with a plastic fly swatter. “You get what’s given to you.”

But as the Caldor fire bore down on this winding forested community some 50 miles east of Sacramento, Olson admitted that something seemed different this time around.

“This is the worst I’ve ever seen it,” he said as he eyed the ominous yellow skies.

Still, he had no plans to evacuate, even after a sheriff’s deputy came by and told him he’d been ordered to do so.

“I’m at the dropping off point,” Olson said. “I don’t much give a damn.”

Across the northern half of California, a relentless series of uncontrolled wildfires have burned more than a million acres and destroyed entire communities in one fell swoop. Exacerbated by the interplay of drought, heat and global warming, extreme fire behavior has profoundly changed the lives of those who live on the doorstep of California’s wildlands.

For many, summer has now become a time of fear, and the canopy of trees that once shaded their homes and streets is now seen as an existential threat. Similarly, smoky skies have become a harbinger of terror, causing residents to wonder when they might be ordered to flee — and whether there will be anything left when they return.

“It’s really challenging,” said Capt. Thomas Shoots, public information officer with the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection.

The Caldor fire, fanned by strong southwest winds, grew exponentially in the days after it began. At times, the fire was spreading so quickly that authorities were unable to accurately map it. As a result, officials have issued evacuation orders for increasingly larger areas.

“When it comes to evacuations we really try to pinpoint the specific area that is going to be in the path, but with the explosive fire behavior that we’ve been seeing in general but especially on this fire — that first 24, 48 hours was pretty surreal — we’re not taking any chances,” Shoots said.

Pacific Gas & Electric is under rising scrutiny this summer as a series of huge fires across Northern California have raged amid hot, dry conditions.

The Gold Rush-era mountain town of Grizzly Flats was evacuated before the Caldor fire burned through Aug. 17. It’s not yet clear whether everyone was able to escape. At least one man was reported missing, his truck found abandoned by the side of the road.

The town was still smoldering five days later. Most houses were reduced to piles of charred belongings with brick chimneys, satellite dishes and propane tanks poking out. Someone’s kitchen pantry stood improbably, dishes still stacked atop the sagging wire shelves. A squirrel with a singed tail clung to the base of a tree, appearing dazed.

A couple miles away, Wil Berndt, 68, watched from a ridgetop as flames raced up the canyon toward his home.

“See where that fire is going? Right there?” he asked, pointing toward a giant column of smoke rising above the trees. “I’ve lived there for 43 years.”

It was the fourth time the fire had made a run toward his house in as many days. Each time, firefighters were able to save it — even after the fire burned up to his property and across the road.

“Yesterday, it was right across the street from me,” he said. “I was in the house, and I was thinking I left the light on in the bedroom. The trees were all on fire.”

“I haven’t gotten much sleep,” he added. “Every day it starts to threaten.”

The former volunteer firefighter and current risk management consultant, who is well known around these parts as “Wil from the hill,” used to love summers here, riding his bicycle through the backroads and going on hikes with his wife.

But now, he’s come to dread this time of year. He blames the increase in damaging fires on a lack of forest management, saying the area has become thick with overgrown vegetation and choked with invasive species.

“It is so sickening to see all that fuel,” he said. “Nobody’s going to pick it up, so it’s got to burn.”

He attributes the buildup to the decline of logging in the once booming mill town. Although that view is somewhat controversial, many scientists agree that vegetation overgrowth has resulted in unhealthy forests that are vulnerable to large, fast-growing fires.

Down in Placerville last week, the evacuation center at Green Valley Community Church resembled a crowded campground. Trailers and tents lined the parking lot, with wire crates housing dogs, cats and macaws.

Robin Berry, who had been staying there since Tuesday morning, was sitting in the courtyard awaiting an update from the fire and sheriff’s officials who brief evacuees each day.

Even if the fire spares all the homes in Pollock Pines, Berry said she’ll still be heartbroken. Her connection to the land goes much deeper than what’s built on it.

“The first day was really hard for me — I just cried,” the 62-year-old said. “It’s a loss of your paradise up there. That’s what it was to me. I could center myself and breathe.”

Berry moved to the town 23 years ago from the Bay Area and fell in love with the tranquil surroundings, taking her border collie for daily swims in a nearby lake.

So it was especially difficult for her to see deer and other wildlife flee the forest as the fire neared. A couple days before they were told to leave, her mother looked outside and thought their horse had gotten out, but it was a bear wandering down their driveway, she said.

“Animals have a sense, a natural instinct,” she said. “They were all coming down out of the mountains.”

Berry is thankful she was able to get out with her mobile home, which was parked in the lot, but she worried about her neighbors who weren’t so lucky. Some who couldn’t find trucks to haul them out in time had to leave their homes behind.

Greenville, a Gold Rush town dating to the 19th century, rebuilt after an 1881 fire. Now it has been destroyed by the Dixie fire, California’s largest this year.

On the other side of the parking lot, a band had assembled in front of a Winnebago.

The American River Jammers are a group of friends, mostly retirees, who have been performing together for years in various incarnations, most recently as a regular reprieve from the doldrums of COVID-19 restrictions. They rebranded themselves the Smoke Jammers as they played Jimmy Buffett and Van Morrison covers for evacuees.

Guitarist Larry Polte’s Camino home was under an evacuation order for the first time since he moved there from Orange County 40 years ago.

“I used to like trees,” he said. “But now, trees just attract fires.”

Polte has been increasingly wondering if another move is in order, given the growing risk.

“My kids have been asking me the same question, but where do you go?” he asked, noting that temperatures have risen across the globe. “You have to keep moving north, with the climate change.”

“Maybe Canada,” he quipped.

Back in Pollock Pines, Olson’s longtime neighbor Charles Lucito Jr., 53, and his pit bull Capone came to visit the shuttered equipment rental business where Olson now lives, bringing a bag of provisions that consisted of three plastic handles of Kessler whiskey. Olson said he already had enough food to last two weeks.

The two men peered into the trees, surveying the scene.

“I keep watching,” Olson said. “If we do get a problem, it will come from that direction right there.” He pointed ahead of him, shifting in his chair to get a better look.

Still, even if the fire reached Pollock Pines, he said he was unlikely to mount a stand like he’s done in the past. Three discs in his spine are gone, and his gout is so severe he can’t climb up into the seat of his bulldozer.

“If it gets that bad, I’ll fire up the ol’ pickup and go to American River Canyon,” he said.

The friends reminisced about one particularly bad winter when Olson had to use his bulldozer to dig out Lucito’s truck multiple times. In the smoky heat, it seemed like a beautiful dream.

The way Olson figures it, there’s no one thing that’s made the fires get so bad. He ticked off the factors that he believes have combined to produce this crisis: more people living in wilderness areas, governments mismanaging water supplies — “the beavers are smarter than the goddamn people running the state” — and, of course, the drought, winds and heat.

“The hotter the weather gets, the more fire danger you get. It’s kind of simple math,” he said. “To live through it, though, is the drizzles.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.