FBI says fortune seized in Beverly Hills raid was criminals’ loot. Owners say: Where’s the proof?

- Share via

After the FBI seized Joseph Ruiz’s life savings during a raid on a safe deposit box business in Beverly Hills, the unemployed chef went to court to retrieve his $57,000. A judge ordered the government to tell Ruiz why it was trying to confiscate the money.

It came from drug trafficking, an FBI agent responded in court papers.

Ruiz’s income was too low for him to have that much money, and his side business selling bongs made from liquor bottles suggested he was an unlicensed pot dealer, the agent wrote. The FBI also said a dog had smelled unspecified drugs on Ruiz’s cash.

The FBI was wrong. When Ruiz produced records showing the source of his money was legitimate, the government dropped its false accusation and returned his money.

Ruiz is one of roughly 800 people whose money and valuables the FBI seized from safe deposit boxes they rented at the U.S. Private Vaults store in a strip mall on Olympic Boulevard.

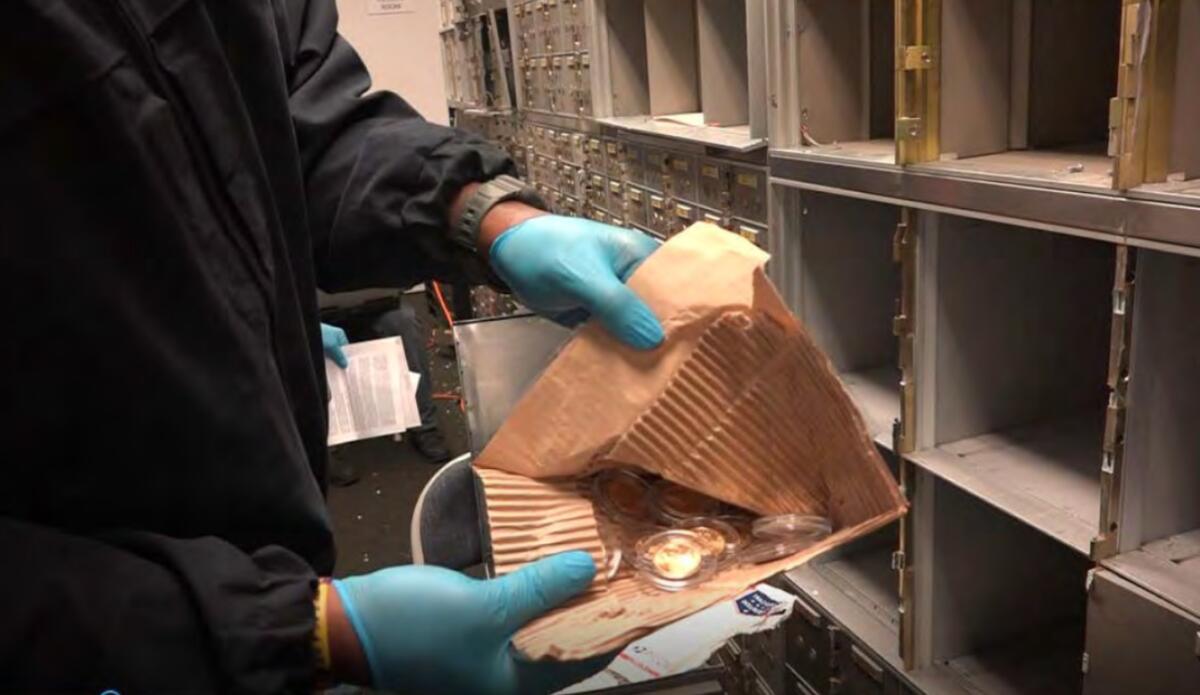

Federal agents had suspected for years that criminals were stashing loot there, and they assert that’s exactly what they found. The government is trying to confiscate $86 million in cash and a stockpile of jewelry, rare coins and precious metals taken from about half of the boxes.

But six months after the raid, the FBI and U.S. attorney’s office in Los Angeles have produced no evidence of criminal wrongdoing by the vast majority of box holders whose belongings the government is trying to keep.

About 300 of the box holders are contesting the attempted confiscation. Ruiz and 65 others have filed court claims saying the dragnet forfeiture operation is unconstitutional.

“It was a complete violation of my privacy,” Ruiz said. “They tried to discredit my character.”

Prosecutors, so far, have outlined past criminal convictions or pending charges against 11 box holders to justify the forfeitures. But in several other cases, court records show, the government’s rationale for claiming that the money and property it seized was tied to crime is no stronger than it was against Ruiz.

Federal agents say the use of rubber bands and other ordinary methods of storing cash were indications of drug trafficking or money laundering.

They also cite dogs’ alerting to the scent of narcotics on most of the cash as key evidence. But the government says it deposited all of the money it seized in a bank, making it impossible to test which drugs may have come into contact with which bills and how long ago.

“You actually don’t know anything until that currency is run through a lab,” said Mary Cablk, a Nevada scientist and expert witness on drug dogs for both prosecutors and defense lawyers. A dog alert to drug residue on cash “might be valid” and “might be complete bunk.”

Customers of U.S. Private Vaults are suing the FBI over its attempt to confiscate gold and silver, jewelry and $86 million in cash from safe deposit boxes.

U.S. Private Vaults was indicted in February on charges of conspiring with unnamed customers to sell drugs, launder money and structure cash transactions to dodge government detection. No people were charged.

The criminal case has remained dormant since then, with no attorney or other representative of U.S. Private Vaults appearing in court to enter a plea. A spokesman for the U.S. attorney’s office in Los Angeles declined to comment on why the case appears to have stalled.

Michael Singer, a Las Vegas lawyer who has represented U.S. Private Vaults on other matters, declined to comment on the charges against the business but said he was unaware of any criminal activity by its owners. He also said the government had “overstepped its bounds” in its search, seizure and attempted confiscation of the customers’ money and property.

In papers responding to 15 lawsuits and other claims filed by box holders demanding the return of their belongings, prosecutors say U.S. Private Vaults intentionally marketed itself to criminals by stressing that customers could rent boxes anonymously.

A U.S. postal inspector alleged in court papers that Michael Poliak, an owner of the business, has admitted to making money from healthcare fraud and illegal marijuana sales. Poliak could not be reached for comment.

Some lawyers for box holders say the government’s entire operation is a “money grab” to acquire tens of millions of dollars for the Justice Department through forfeiture. A spokesman for the U.S. attorney’s office denied that and said some of the money it recovers will go to crime victims.

In civil forfeitures, no criminal conviction is required. The government just needs to prove that it’s more likely than not that the money or property it seeks to confiscate was linked to criminal activity.

The lax standard of evidence was apparent in the forfeiture complaint filed Monday against two brothers from Woodland Hills. The government wants to keep the $960,100 in cash it took from one of their safe deposit boxes and the $519,000 it took from the other.

Prosecutors say that theft, fraud and money laundering justify the forfeiture. But the complaint’s only evidence was that one of the brothers — it did not say which one — had allegedly “been in contact with” suspected armed robbers of cellular phone stores.

Their lawyer, Benjamin Gluck, called the complaint “an appalling and unconstitutional abuse of power.”

Prosecutors also produced scant evidence in another forfeiture case to confiscate more than $900,000 from a box holder whose identity they have been unable to learn. They accused him of being “either a top-level drug trafficker or money launderer.”

The “indicia” of those crimes included the way the person bundled his cash in thick, thin and broken rubber bands; tightly tape-wrapped paper; bank bands; and plastic CVS and paper Good Neighbor pharmacy bags.

Using the pseudonym Charles Coe, the box holder has filed suit challenging the seizure of his money.

Gluck, who represents Coe, declined to discuss the specific case but said U.S. Private Vaults customers “included many immigrant business owners who escaped repressive regimes where banks are unsafe and have collected amounts of cash as their life savings over many, many years.”

“The notion that the old rubber bands mean they must be drug dealers is ludicrous,” he said.

The government’s only other evidence against Coe is a drug dog’s alert on his cash.

The declining value of dog alerts as more states legalize marijuana is well known in law enforcement. Police across the nation have begun retiring drug dogs that alert for marijuana and training new ones to find only cocaine, methamphetamine and heroin.

But Smithy, the LAPD dog that sniffed Coe’s cash, is trained to detect marijuana too. In his eight-year career as a drug dog, Smithy’s work led to the seizure of more marijuana than the other three drugs combined, according to a court statement by his handler, Officer Dolores Suviate.

Billions of dollars in cash cycle daily through businesses that sell marijuana, and experts say that leaves a detectable odor on bills that wind up in the hands of people who are neither dealers nor users.

At U.S. Private Vaults, at least two boxes contained large sums of cash from licensed marijuana businesses that cannot open bank accounts due to federal laws banning the sale and possession of the drug, according to box holder lawyers. The safe deposit boxes were not airtight, so the scent of marijuana could spread among them.

On Friday, prosecutors filed complaints to confiscate money from more box holders. In two of the complaints, the government sought forfeiture of $154,600 in cash from one box holder and $330,000 from another. Beyond dog alerts, the main evidence was that both had applied unsuccessfully for state licenses to sell marijuana, suggesting that “the funds are drug-related,” Assistant U.S. Attys. Victor Rodgers and Maxwell Coll wrote.

Thom Mrozek, a spokesman for the U.S. attorney’s office, called dog alerts on cash “strong evidence” of drug crimes but said they were “not the only factor contributing to probable cause.”

“Using dogs to identify marijuana-tainted money is entirely appropriate,” he said. “To begin with, marijuana is illegal under federal law. But it is also illegal to traffic in marijuana under California law without having an appropriate license.”

As for Ruiz, Mrozek said the government never accused him of a crime, but found “probable cause to believe that the funds in his box were linked to drug trafficking.”

In preliminary rulings, U.S. District Judge R. Gary Klausner blocked the government’s forfeiture cases against Ruiz and three others, saying the lack of any “specific factual and legal basis” violated their rights to due process.

Klausner also found “the facts and the law clearly favor Ruiz” in his claim that the FBI ran afoul of the protections against unreasonable searches and seizures in the 4th Amendment.

Looming over the legal skirmishes is the possibility that Klausner or another judge will grant the box holders’ request for a ruling that the entire raid on U.S. Private Vaults was unconstitutional. That would jeopardize prosecutors’ ability to use any evidence seized from the safe-deposit boxes in both forfeiture and criminal cases.

In warrants authorizing the search and seizure of all “business equipment” at U.S. Private Vaults, U.S. Magistrate Steven Kim placed strict limits on the government, explicitly barring federal agents from searching the contents of each box for evidence of criminal wrongdoing.

In the warrant application, submitted by Assistant U.S. Atty. Andrew Brown, a statement by FBI agent Lynne Zellhart assured Kim that agents’ inspection of each box would “extend no further than necessary to determine ownership” so that belongings could be returned once the government took an inventory of the property seized.

Box holder lawsuits allege that those promises were false and that agents, with no probable cause, intended from the start to rummage through the boxes looking for evidence in the criminal investigation.

Jane Bambauer, a law professor at the University of Arizona, said that under the restrictions Kim imposed on the search, the use of drug dogs to sniff cash inside the boxes was a 4th Amendment violation.

“In terms of just real-world, commonsense assessments of how this should work, what happened was wrong,” Bambauer said. “I think it is also pretty clearly wrong on 4th Amendment doctrine terms.”

The feds suffer court setbacks in their effort to confiscate $86 million in cash seized from safe deposit boxes they were legally barred from searching.

The U.S. attorney’s office denied misconduct. Mrozek said “nothing requires the government to ignore evidence of a crime that it sees” while taking inventory of seized goods.

“The search and the seizure of items from the U.S. Private Vaults facility were authorized by a federal judge, and the entire operation has been conducted in accordance with the Constitution and applicable laws,” he said.

Robert E. Johnson, a lawyer representing Ruiz and six other box holders in a class-action suit seeking destruction of all records generated by the search, sees the case as an alarming sign of government efforts to “criminalize financial privacy.”

“The government’s theory is that having cash makes you a presumptive criminal, and I think every American should be worried about that,” said Johnson, a senior attorney at the libertarian Institute for Justice in Virginia.

In the defunct Ruiz forfeiture case, the FBI laid out in a court statement the government’s “probable cause” to believe that his $57,000 came from drug trafficking.

Agents checked on Ruiz’s “holysmokescrafts” email address, discovered his sideline making bongs and concluded he “may be involved in the cannabis industry in other ways,” Zellhart wrote.

The FBI checked state records for Ruiz’s wage and tax history and saw just $18,510 in income since 2019, “less than a third of the cash in the box,” she said.

An FBI review of court records yielded nothing to verify Ruiz’s claim that his money came from legal settlements, according to Zellhart. Once Ruiz turned over records confirming the payments — one for a car accident injury and another for chronic housing code violations at his apartment building — the FBI, under court order, gave back his money.

“They pulled a bank heist in broad daylight,” Ruiz said. “They didn’t even apologize.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.