Column: Reintroducing the series ‘Black L.A.: Looking at Diversity,’ 39 years later

- Share via

It was billed by the Los Angeles Times as an “unprecedented” endeavor. The “Black L.A.: Looking at Diversity” project would be a window into the lives of ordinary Black folks, who were neither criminals nor celebrities. The series would be reported and written entirely by the newspaper’s small contingent of Black journalists.

The year was 1982 and, like most of my Black newsroom colleagues, I was still wounded and fuming over an incendiary front-page series The Times had run the year before titled “Marauders from inner city prey on L.A.’s suburbs,” depicting young Black men as “savage” inner-city “marauders” preying on the city’s wealthy white suburbs.

That project was produced with no Black input; reported, written and hyped by white colleagues who seemed oblivious to its promotion of vile stereotypes. So if our Black series was “unprecedented,” that’s only because distorted coverage like that had been the norm.

In the summer of 1982, The Times published a series on Southern California’s Black community called “Black L.A.: Looking at Diversity.”

That sensationalized portrait of a small criminal fringe was a disservice to our readers, discredited our paper, and made our job, as Black reporters, much harder to do.

It didn’t take long for Black staffers to harness our outrage and marshal our forces. We aimed to counteract the damage that had been done; to offer up a truer portrait through voices and stories from Los Angeles’ vibrant and evolving Black communities.

Our newsroom ranks were small; there were hardly more than a dozen Black reporters on a staff of several hundred back then. We had a few seasoned journalists, including former Time magazine correspondent Ed Boyer and veteran Austin Scott, who’d spent decades as a reporter for the Associated Press and the Washington Post. But most of us were young and relatively new to The Times. Some, like Janet Clayton and Pamela Moreland, had been born and raised here and knew the city well. Others, like John Mitchell and me, had been hired from across the country to staff the paper’s new suburban sections.

We’d all witnessed or experienced encounters with racism over the years, in the newsroom or on the streets. Done right, this project could enlighten readers and help us all better reckon with the toll of racial bias.

Times reporter Louis Sahagun was part of the 1984 team that won the Pulitzer prize for Public Service.

To give our project the sweep of history, we opened with Ron Harris’ story of four generations of a Black family that migrated here from Texas in 1910 — and ultimately helped change the complexion of Los Angeles, when they challenged the “restrictive covenant” that blocked them from living in a house they’d built. Their lawsuit was among a surge of complaints that led the U.S. Supreme Court in 1948 to invalidate covenant restrictions that barred people of color from moving into white neighborhoods. Still, many white landowners continued to discriminate, until the covenants were finally declared illegal in 1968 by the federal Fair Housing Act.

That opened new housing opportunities, and by the time our series ran in 1982, there were more than a quarter-million Black people living in middle-class suburbs like Carson, Long Beach and Pasadena.

The 1970s and ‘80s had been heralded as our glory years — the “post-civil rights movement era,” academics and the media called it. Official barriers to full participation in society had fallen: Federal legislation had ended legal segregation, enshrined protection of voting rights and outlawed discrimination in renting or buying housing.

And while Black people did indeed make great strides — particularly in the political, business and entertainment spheres — the media’s portrayal of us was still mostly two-dimensional: the tragedy of rising crime and failing schools, or the glittery exploits of professional athletes and rich entertainers.

And the progress had come with roadblocks and costs. We reflected on our own lives to find ways to illustrate that. The project gave us permission to draw on our insights about life with Black skin.

Reporter Lee Harris shared a tale of trying to find a place to rent when he was hired for his first newspaper job, after graduating from Cal State L.A. in 1968. Harris and his wife were repeatedly turned away — even though his white boss accompanied them — while white couples were routinely ushered in to see vacancies.

Janet Clayton wrote about the wearying pressure that came with being one of the few Black faces in professional workplaces, where white employees could mingle effortlessly, but more than two Black people fraternizing were apt to be scrutinized or mocked. Clayton would later become the editor of the Times editorial pages, and ultimately the newspaper’s assistant managing editor.

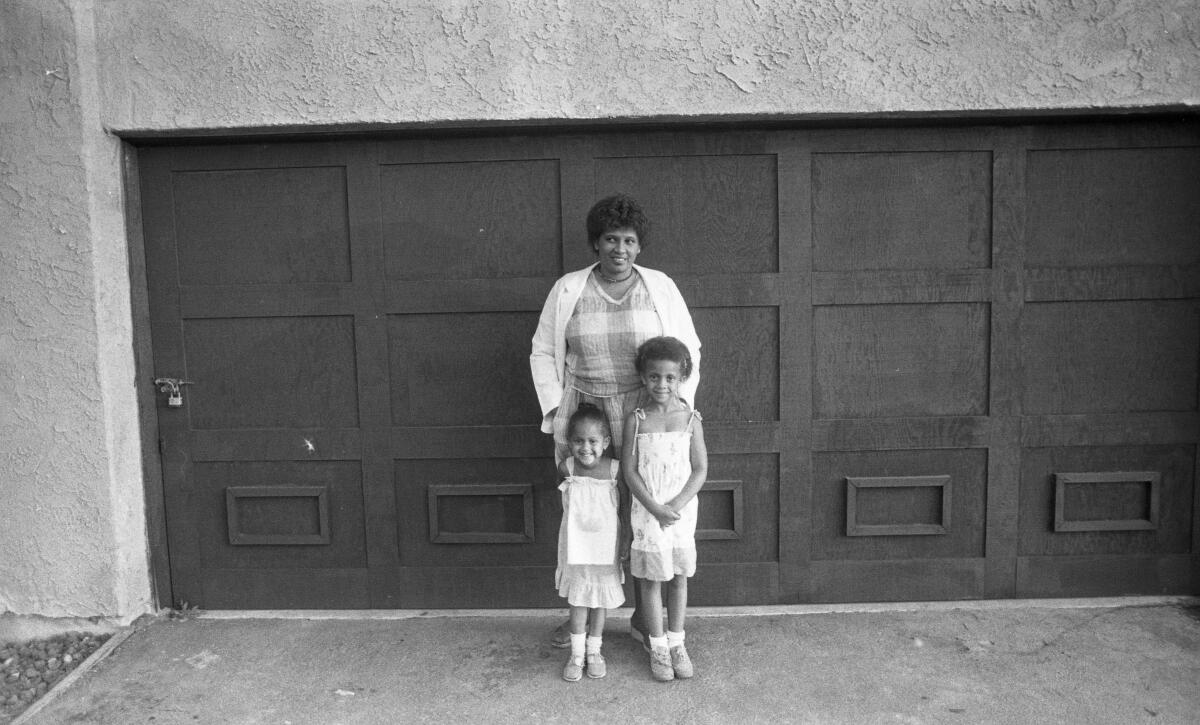

My contribution was sharing the stories of Black families living in San Fernando Valley neighborhoods that had for decades been notoriously whites-only. Two years earlier, my husband and I — who both grew up in Ohio in Black communities — had moved into one of those Valley neighborhoods, and wound up perpetually recalibrating what we loved and what we’d lost in the move.

Suburban living offers a challenge to blacks that white suburbanites never have to face: coping with feelings of cultural isolation and alienation.

Now, four decades and three grown children later, I still live there — on a block that is now so diverse, it’s hard to remember that we were once its token minorities.

Rereading our series resurrected that era for me; our stories reflect both the desperation I felt, and our group’s collective sense of responsibility. They were rich with details that others might not have seen.

I’m struck by how prescient some of those stories now seem — like Pam Moreland’s piece on how racism pushed Black women to succeed — but also by how little some fundamental issues have changed. Discrimination may not be as blatant today, but attitudes still protect and propel it.

Just last year, my apartment-hunting daughter in the Bay Area couldn’t get a response to her many inquiries about posted vacancies, until she removed her profile photo from the emails she sent. When her Black face disappeared, the responses began to roll in. She loves her new digs, but the hurt still stings.

We can’t sugarcoat the tensions that diversity brings, but our series tried to widen the lens so “truth” isn’t shaped by a single perspective.

Times reporters had written reams over the years about white parents’ resistance to busing their children across town to desegregate schools, but it fell to us to reveal the angst of Black parents who wanted their children in integrated schools, but worried that some white classmates would be cruel.

That kind of holistic coverage is the standard today, and a necessity in a region that is so divided and diverse. Now, more than ever, we need to be reminded that every voice has value, and we’re all beholden to history.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.