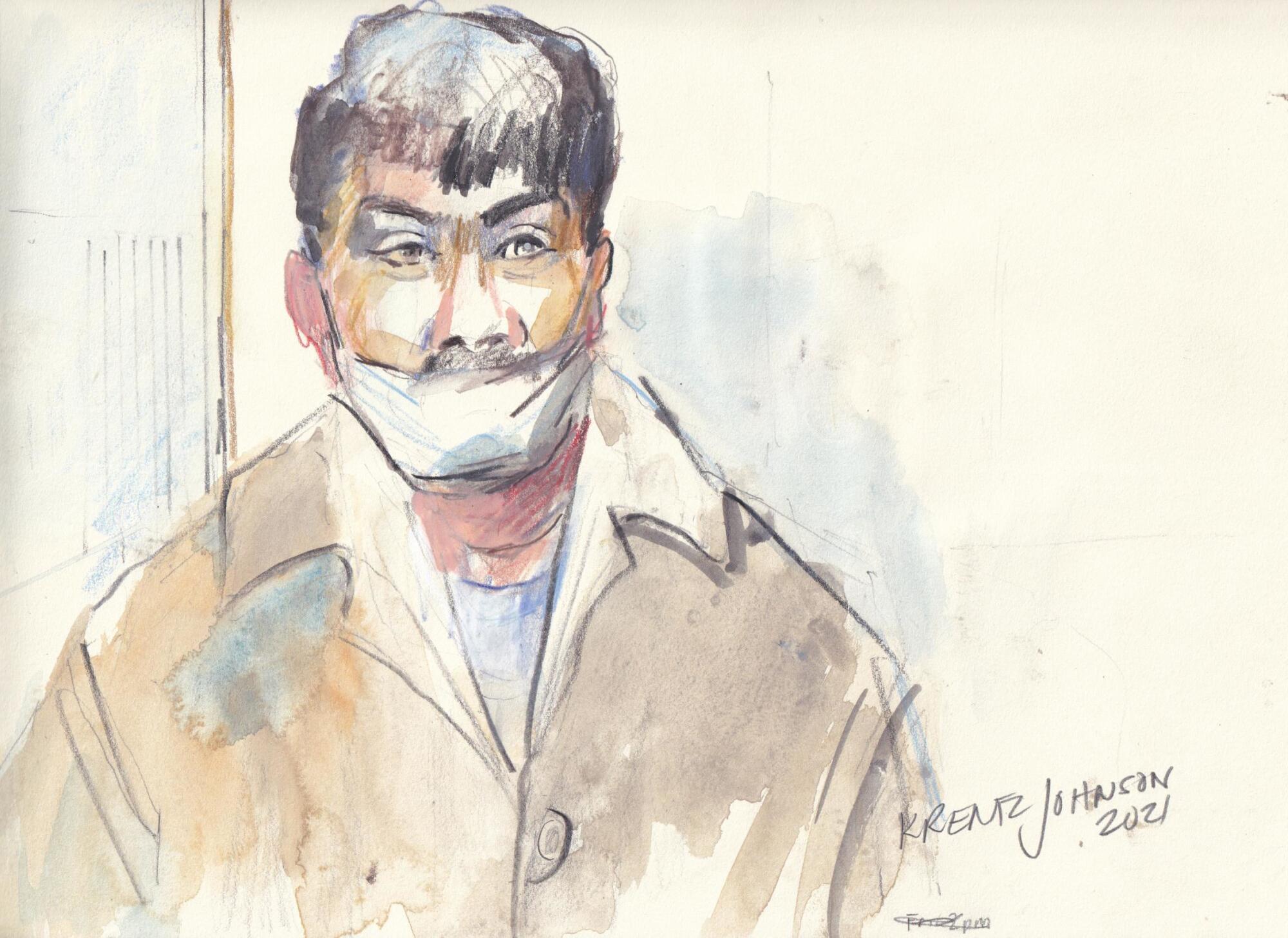

SAN DIEGO — Antonio Hurtado was what the boating community calls a bouncer.

Known simply as Tony, the 39-year-old roamed San Diego Bay living aboard an old boat, bouncing from anchorage to anchorage without the means to pay for a permanent mooring.

He had a string of petty drug convictions, no job and an unreliable boat that needed fixing. And he owed people money, several boaters in his tightknit community told the Union-Tribune.

But, as April turned to May, he seemed optimistic, telling fellow bouncers that he was finally going to be able to pay off his debts.

Just how became clearer days later.

On May 2, the black-hulled trawler he’d been living aboard — one of those unpaid debts — smashed onto the rocks below Cabrillo National Monument off Point Loma, sending him and 32 undocumented immigrants into the sea. Three of them drowned.

Hurtado is now jailed in San Diego on charges of human smuggling, as well as accusations of assaulting a Border Patrol agent after his arrest. He has pleaded not guilty.

Hurtado, a U.S. citizen, does not cut the typical profile of an alleged maritime smuggler.

While Americans are being increasingly recruited by smuggling networks to sneak migrants into the country — last year U.S. citizens made up 71 percent of human-smuggling offenders sentenced by federal courts, according to data — they are primarily used in land-border crossings.

The maritime routes off San Diego’s coast, on the other hand, have typically been navigated by Mexican fishing boat captains, according to federal investigators.

“It’s about access to the water, access to the boat, access to experience,” said Christopher Davis, an assistant special agent in charge with Homeland Security Investigations in San Diego and head of the Marine Task Force.

“The reality is, it’s a low-risk, high-reward operation,” he added. “The chance of being caught is very minimal.”

That’s even with the steep rise in maritime smuggling in recent years and subsequent increase in patrols by border authorities.

Apprehensions of migrants and suspected smugglers at sea along the Southern California coastline nearly doubled from fiscal 2019 to 2020. They have continued to climb in fiscal 2021, with 1,460 apprehensions as of July 20 and two additional months left to tally, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

Many of the maritime runs are made in pangas, rudimentary wooden fishing boats with an outboard motor that can pull up to beaches. One of the latest attempts, last weekend, ended with Border Patrol agents finding an unconscious girl or woman in the water off Carlsbad State Beach. The panga, and any other migrants involved, were gone by the time authorities arrived.

Organizations are also known to use pleasure craft such as sailboats and cabin cruisers to blend in with recreational traffic, unloading migrants one or two at a time at public and private marinas, Davis said.

Oftentimes, smuggling organizations buy the nicer boats on the Southern California resale market, under a fake name, and take them south to Mexico to be put to work, Davis said. Asking a U.S. boater to use their own craft is a more unlikely scenario, he added.

Little has been publicly released about Hurtado’s alleged involvement in the smuggling effort or how he may have been recruited. His attorney did not respond to requests for comment.

Jeremy Warren, a San Diego attorney who is not connected to the case but has represented several U.S. citizens charged with smuggling over the years, said people with substance abuse issues and in desperate need of money are common targets for recruitment. They often have some tie to Mexico.

“All these people are fodder for organizations, whether it’s drug smuggling or people smuggling,” Warren said. “They use these people interchangeably and could care less if they are arrested. They use them and lose them, move onto the next.”

The ‘Zoo’

The last several years of Hurtado’s life have been marked by drug addiction, short stints in jail, and a transient lifestyle that kept him moving from anchorage to anchorage in a cat-and-mouse game with harbor authorities.

He lived on the water among a larger community of live-aboard boaters who also do what’s known as “the bounce.”

Many in the group of 100-plus are unable to afford a permanent slip or mooring, have bad or nonexistent credit, or have a boat that is unregistered or can’t pass inspection. Some just love the water and want to live off the grid.

They tie up at the Shelter Island Guest Dock or one of two anchorages in San Diego Bay when they can — permits are required, and they are limited.

The rest of the days they anchor at the Zuñiga Jetty Shoal — a shallow spot at the mouth of San Diego Bay between Point Loma and Coronado’s North Island — that leaves boats at the mercy of the open sea.

Boaters have a nickname for the place: the Zoo. It can be especially treacherous in winter.

Hurtado has been charged with at least a dozen different crimes in San Diego County, mostly low-level drug charges, dating back to 2013.

The charges include possession of methamphetamine, possession of marijuana, possession of drug paraphernalia, and transportation of a controlled substance.

In July 2018, Hurtado was accused of stealing a boat from the Chula Vista Marina and moving it to La Playa Cove off Point Loma, according to court records.

Hurtado and a woman he identified as his girlfriend told Harbor Police that they had bought the $29,000 boat — named Bona Ventura — from a woman who was in jail on federal fentanyl and meth charges.

The boat’s owner told officers she never sold it.

Maria Eugenia Chavez Segovia was among three Mexican nationals who drowned at sea when an overloaded trawler-style boat ran aground

Hurtado and his girlfriend later admitted they were “working on a purchase program with the owner” but had not made any payments for the boat, which they were living on, and said they had forged the bill of sale, court records state.

Hurtado pleaded to a lesser charge in the case.

He later acquired another boat, which he lived aboard for more than year before the fatal wreck.

Barry Dorman, a weathered, veteran bouncer, sold Hurtado the Salty Lady — a 40-foot classic trawler, painted matte black — for about $1,000. Hurtado told friends that he was interested in maybe becoming a fisherman.

Hurtado was about $500 short, but Dorman signed over the title anyway and told Hurtado to pay him the rest when he could, Dorman said.

“He was starting to get his act together,” Dorman said. “He didn’t seem like he was back on drugs.”

Hurtado would pay off a little at a time. But Hurtado apparently never sent in the paperwork to take over title. Dorman assumes Hurtado didn’t have the money to pay the transfer fees at the DMV.

“He didn’t complete the deal,” he said. “He left me stranded.”

Dorman and other boater acquaintances said Harbor Police frequently ticketed Hurtado aboard the boat for illegal mooring. Each time, Dorman would be notified, since the boat was still in his name, and he’d reiterate that he’d sold it to Hurtado, he said.

The Port of San Diego was not able to fulfill a records request for citations and other documentation by time of publication.

Those who know Hurtado said it was no secret that he owed people money, had a drug addiction and was afraid his boat would be taken from him. However, he was not known to make trips to Mexico, and several acquaintances said they wouldn’t have suspected Hurtado to get involved in smuggling.

“He’d been down here for years with no coyote runs,” said fellow bouncer James Bryant. “As far as I know, that was his first go of that. It was very much the move of a desperate person.”

Terror at sea

It was mid-morning on a Sunday when sightseers visiting Cabrillo’s lighthouse and tidepools watched with horror as a boat ran aground about 50 feet from shore.

Passengers jumped into the water as the vessel listed dangerously to the side and started to flood. Some on board were able to swim to shore while others were caught in a rip current. Bystanders, including Navy sailors, jumped into the waves to join the lifeguard rescue effort.

The boat soon broke apart on the reef.

Three Mexican migrants suffered blunt-force trauma and drowned: Victor Perez Degollado, 29; Maria Eugenia Chavez Segovia, 41; and Maricela Hernandez Sanchez, 35.

The passengers, who told authorities that they had paid $15,000 to $18,000 to be smuggled into the U.S., identified Hurtado as the pilot of the boat, according to the criminal complaint.

Trial is set for January in the case, which has already generated more than 2,000 items of discovery, including videos of the crash, photos, witness interviews and reports from nine agencies, according to a recent court filing. Pieces of wreckage — including possibly the ship’s sunken engine — are also being analyzed.

The trouble on the boat began early in the middle-of-the-night journey, Eberardo, a passenger who wanted to be identified by his first name only, recounted to Reuters in an interview.

He and others described Hurtado’s behavior as erratic. Hurtado, who didn’t speak Spanish, kept falling asleep at the wheel, and Eberardo told Reuters he would nudge Hurtado repeatedly to awaken him.

The passengers told Reuters that at one point, Hurtado dropped the anchor in an apparent attempt to steady the vessel, which was being tossed by rough seas. But when he tried to raise anchor after a few hours, it wouldn’t cooperate. Eberardo said he cut anchor. Then the motor died.

That’s when the boat began to sink.

The smuggling organization had earlier assured the passengers, and their families, that the trip would be safe.

One of Chavez Segovia’s sisters, who lives in Salinas and did not want to be identified by name out of fear for her safety, was told by a man on the phone beforehand that the boat would be big, that it would launch from Ensenada and would stop at a restaurant on the way so it would not look suspicious.

Similarly, Eberardo was told to dress the part of a tourist, according to the Reuters interview.

The Salty Lady’s intended destination has not been publicly revealed. Such a boat would either need to unload passengers at a dock or ferry them to shore via a dinghy. Both methods are commonly seen in San Diego, according to investigators.

Migrants paying for passage often don’t have choice in the matter, much less who ends up at the helm.

Just three weeks after the Point Loma shipwreck, a migrant on an overloaded panga drowned off La Jolla. The smuggling organization had tasked two undocumented migrants with the job of piloting the boat in lieu of paying their own smuggling fees.

“Once they are put on that vessel,” said Davis, the Homeland Security task force leader, “they are at the mercy of the boat captain, the wind and the sea.”

Staff researcher Merrie Monteagudo and Los Angeles Times reporter Andrea Castillo contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.