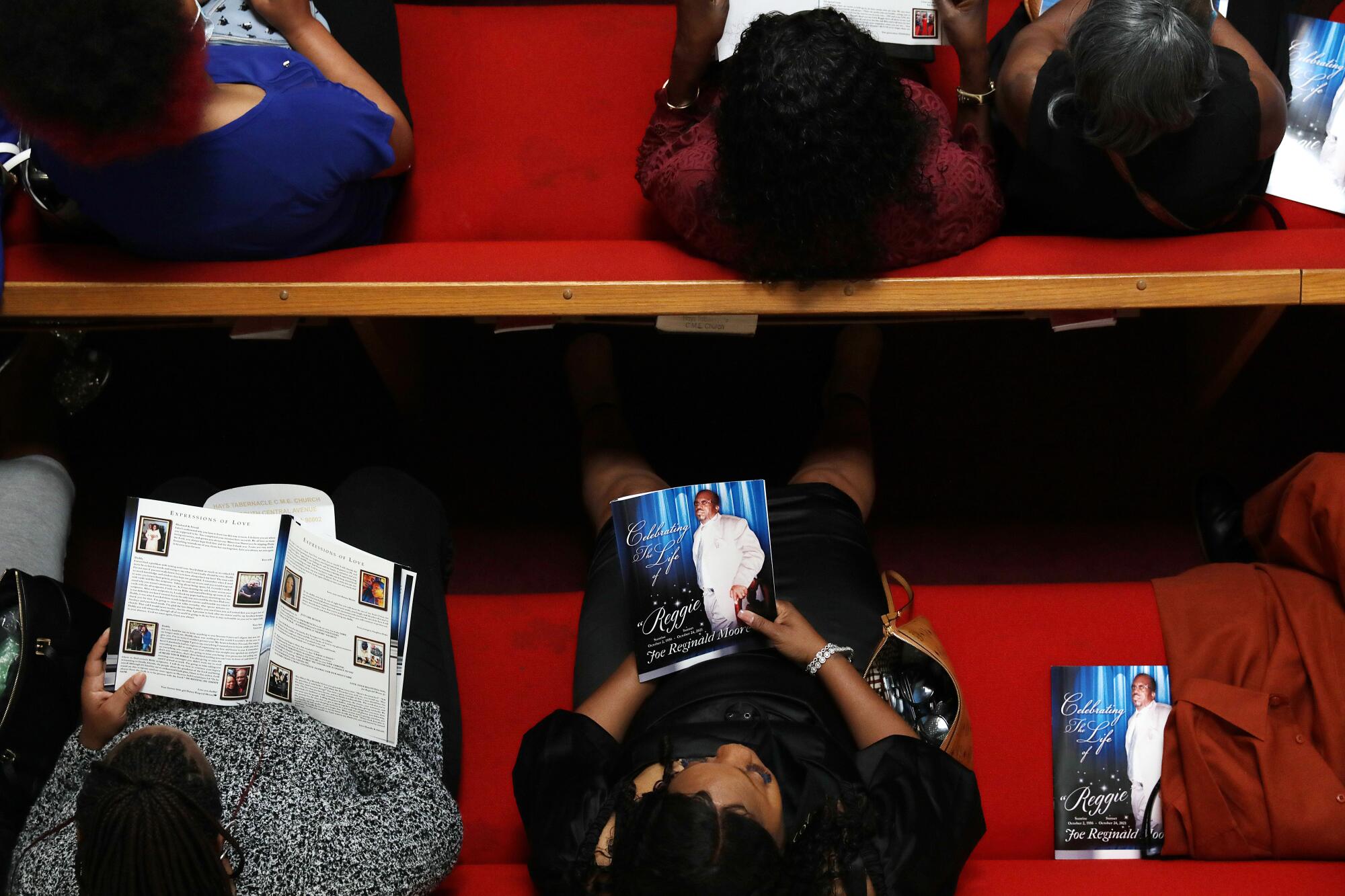

It was about halfway through the nearly three-hour funeral service for associate pastor and Sunday school teacher Joe Reginald Moore Sr. when his niece somehow got a hold of the microphone.

“There was a time that I didn’t even like to look at him!”

The people in the pews, deep into their grief by then, gasped. But Sandra Gladney continued undeterred.

“I’ll repeat — amen — there was a time that I didn’t even like to look at him!”

Gladney was getting at a truth already known to most of the people who came to Hays Tabernacle CME Church on Friday morning. They just weren’t entirely prepared to talk about it while they were mourning all that Moore had brought to their lives before he was brutally gunned down in the middle of the day outside his Compton church.

The truth is, though, Moore — or “Reggie,” as everyone called him — wasn’t always a man of God.

He spent several years in the 1980s and 1990s addicted to crack cocaine. His relatives say he was never in a gang (unlike some other members of their family), but he did get drawn into the sort of trouble that often comes along with drugs.

That only a few decades later, he would be eulogized with proclamations from the city of Compton, read aloud by Mayor Emma Sharif, and from California Assemblymember Mike Gipson would’ve been unthinkable.

But Moore was a man willing to change — and to forgive himself and others. And he wanted everyone he met to do the same.

As one family friend explained Friday morning, looking out over the sea of Black faces, many of them in royal blue and white: “We did a lot of things together, but he became a hustler for God.”

::

Gladney arrived at Upper Room Christian Center not long after Moore had been found lying unmoving in the street, a bullet wound to the chest.

“I can still see him,” she told me a few days ago, sitting on a couch at her cousin’s home. “He wasn’t covered yet.”

The 67-year-old Moore, known for his constant jokes and mellow attitude, had just finished teaching a Bible study class that Sunday in late October. He had stepped outside for a short break before the main worship service started when he was ambushed.

The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department has said that Moore was the intended target but hasn’t publicly identified a motive yet. A gray sedan was seen fleeing the scene, near Compton Boulevard and Dwight Avenue.

William Gude’s Twitter feed is normally full of videos criticizing police. Now his tweets are about ways to prevent others from sharing his son’s fate.

The shooting was merely the latest in a string of violent crimes — both drug-related and gang-related — that began ticking up during the darkest days of the COVID-19 pandemic and haven’t let up yet.

As of mid-October, the city of L.A. had recorded 320 homicides this year, putting it on track to top the 355 last year. In fact, the way things are going, there could be more people killed this year than in any year since 2006.

Most often, the victims are Black.

Like Moore. And before him, like his 27-year-old grandniece, Dominique. She was shot to death in Watts last month.

The violence troubled Moore deeply. He was known for preaching to anyone and everyone who would listen to put down their guns and to turn their lives around. He carried pamphlets with him, extolling the need to give one’s life over to Christ. To be saved.

Sometimes it worked.

At the funeral on Friday, Sabrina Colbert shyly approached the microphone to talk about her Uncle Reggie. He was the one who convinced her to change and, at last, to deal with her addiction to drugs.

“I used to try to run from him,” she recounted with a sad chuckle. “He would say, ‘Hey! Where you going?’”

Colbert’s voice cracked as she spoke about the devastation of losing her daughter, Dominque, and then Moore just a few days later. But she vowed to stay strong, fight through the grief that seemed to be radiating off her, and stay in the church.

She looked over at the gray casket surrounded by flowers. “I just thank God that he got a chance to see me clean,” she said.

::

One thing that was made clear by the many, many people who praised him on Friday: Moore understood human fallibility and fragility more than most. In fact, he had a constant reminder.

Decades ago, while still addicted to drugs, Moore ended up in a bad car accident.

“That’s why he walked with a limp,” Gladney told me. Moore’s daughter Raqueal nodded in agreement, dabbing her eyes with a tissue.

Neither remembers all the details. Why he was in the car, for instance, or even whether he was driving or was a passenger. But what both women do remember is that, at some point, Moore’s heart stopped and he was resuscitated.

The 67-year-old was shot in the chest outside the church where he had just led a Bible study on Sunday. He was holding a cane, a Bible and his car keys when he was found lying in the street.

“That’s what made the change,” Gladney said. “Him and God had a conversation.”

The accident left Moore in the hospital for weeks. He had to have multiple surgeries and somewhere along the way, he also kicked his addiction to crack cocaine and rediscovered religion.

“He never had to go to a rehab,” Gladney said. “But he used it as a ministry. So he turned the negative into a positive.”

But in case he ever wanted to forget about the rough-and-tumble years he spent in the streets, he couldn’t because the accident left him with that limp. The limp is why he walked with a cane. And it was his cane — and his Bible — that Moore was holding when he was found lying dead in the middle of the street.

“Our family is not a stranger to death and all that, but this one we just didn’t see coming,” Gladney said.

“He wouldn’t hurt a fly,” added Raqueal, her voice beginning to crack. “So I don’t understand why someone would hurt him.”

Still, they both insist his journey is why Moore spoke so much about forgiveness and why he would be the first to do so, even for his killer.

“Even though he changed, he didn’t sit in a corner with it,” Gladney said. “He went out there to let the community know there’s nothing that you did that God won’t forgive.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Erika D. Smith

Commentary on people, politics and the quest for a more equitable California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.