Column: Don’t let Jacqueline Avant’s shooting get pulled into L.A.’s crass politics of crime

- Share via

Michael Lawson spent Thursday morning choking back tears before a bank of TV cameras in Leimert Park.

He didn’t know that police had already identified a suspect in the brutal fatal shooting of Beverly Hills philanthropist Jacqueline Avant. He only knew that he needed to do everything possible to get justice for the 81-year-old woman who had loved him like family. So he called a news conference to talk about it.

“We just wanted the world to know how important this was to us,” the president and chief executive of the Los Angeles Urban League told me. That it was a “shot to the hearts of all of us.”

A few hours later, Beverly Hills police would reveal at their own news conference that they had arrested a 29-year-old Los Angeles man with a lengthy criminal record for burglary and robbery.

And a few hours after that, L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti, flanked by members of the LAPD and FBI, would talk about his friend Avant and then quickly pivot to the rash of “smash-and-grab” and “follow-home” robberies.

A 17-year-old girl called police after she heard a gunshot and a man yelling outside her bedroom door. Police say he killed a Los Angeles philanthropist an hour earlier.

Beverly Hills Police Chief Mark Stainbrook used his time before the cameras to send a message to anyone thinking of committing a crime in his city. “You will be caught and brought to justice,” he declared.

Garcetti used his time to assure Angelenos that there’s no cause for alarm, citing the arrests of 14 people suspected in the store robberies. Police Chief Michel Moore also made a point of crowing about a coming influx of new officers.

“This is still [the] safest decade, probably of our lifetimes,” Garcetti said. “I’m always careful when I say that because it means nothing if you are a member of the Avant family. If you’re a member of a family that was attacked today. We never dismiss that. We also don’t want it to blow up where everybody thinks that suddenly we’re seeing statistics way beyond what the actual numbers are.”

In other words, there’s crime and then there’s the politics of crime. And, at the moment, it’s the slippery slope of the latter that I’m most worried about.

::

Michael and his wife, Mattie McFadden-Lawson, cringe just thinking about whether the senseless slaying of their dear friend could become some sort of political football.

When I reached the couple on Friday morning, they told me about how they met the Avants back in 2003. That first meeting, during a reception at Morehouse College, proved to be pivotal in their lives and in the lives of their children.

“We just bonded immediately,” McFadden-Lawson said. “We said once we get back to L.A., we would be in touch. And we have remained in touch ever since.”

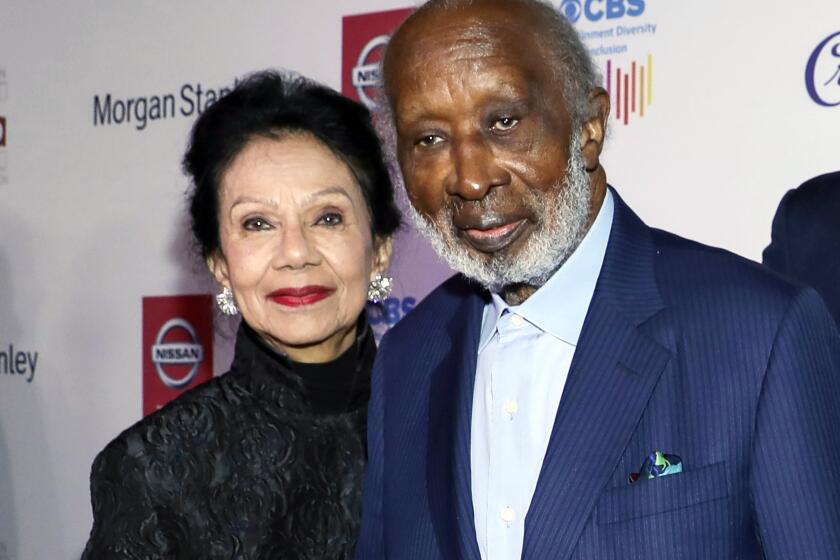

Before her death, Jacqueline Avant was known to many as the wife of Clarence Avant, a music industry titan who helped generations of Black artists succeed, from Bill Withers to Babyface to Jay-Z.

But Avant was a woman who quietly took on causes to help people, particularly in the Black community of South L.A. In addition to serving on a number of charitable boards, she was instrumental in the opening of Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital in Willowbrook.

“She never sought after the limelight. She had her own life,” McFadden-Lawson told me. “And wherever she went, she would light up with her presence, because she was just a very elegant woman, always extremely well-dressed, well-spoken and she cared.”

As close friends, Avant and McFadden-Lawson would go for tea and spend long lunches talking about books and art. The families also would celebrate birthdays and weddings together.

Jacqueline Avant helped unite the worlds of Black entertainment, sports and politics. One friend called her “the queen of the people.”

It was the Lawsons who introduced then-Sen. Barack Obama to the Avants. And it was the Avants who helped Obama gain a foothold in Southern California’s entertainment and political circles.

The last time the Lawsons saw the Avants was the day before Thanksgiving. They had stopped by the Avants’ Beverly Hills home to drop off dessert and ended up spending five hours together, never thinking it would be the last time they spoke to Jacqueline.

“This is about a woman who lost her life in the most horrific way and is no longer with us,” McFadden-Lawson told me. “Let’s think of her in terms of all the good that she brought to this world, and how she tried her best to lift others through her service and through her philanthropy.”

She paused and took a deep, frustrated breath.

“That is the narrative that Clarence and his family would want everyone to focus on.”

The Lawsons know that might not happen, though.

::

Across California, but particularly in Los Angeles and the Bay Area, many people were on edge long before last week’s fatal shooting.

For weeks, we’ve been hearing about robbers pillaging luxury and chain stores, in some cases assaulting employees. That’s in addition to the people who have been robbed of their watches and wallets at gunpoint, or have been followed home and targeted, including a star of “The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills” and a former host of BET’s “106 & Park.”

For far longer, the district attorneys of Los Angeles and San Francisco have been under fire for their progressive takes on prosecution and sentencing.

Political candidates, ranging from those vying to be the state’s next attorney general to those hoping to be reelected sheriff, have started insisting California is in chaos because of such reform-minded policies.

Meanwhile, law enforcement agencies are looking for reasons to beef up their budgets after funding cuts because of the COVID-19 pandemic and, in many cases, because of calls from activists emboldened by the racial reckoning prompted by George Floyd‘s murder.

And then came the gut-wrenching news about Avant — arguably the most high-profile and, for Black Angelenos, distressing act of violent crime in Los Angeles County since the fatal shooting of rapper and activist Nipsey Hussle.

A string of incidents at private homes and public spaces has catapulted crime in Los Angeles back into the zeitgeist.

It didn’t take long after Beverly Hills police announced they had arrested Aariel Maynor, saying he had entered the couple’s Trousdale Estates home with an AR-15 rifle, for the “I told you so’s” to start on Twitter. Then photos and video of Maynor brought the racist trolls out of their basements.

The Lawsons have a hard time thinking about how Avant died in the house where they had just spent so many hours with the Avants. They want justice and they want punishment (because, seriously, who in the hell shoots an 81-year-old woman?).

But assuming the allegations against Maynor are found to be true, the Lawsons also see what happened as a failure of the system.

“I don’t know this person,” Lawson said of Maynor. “I don’t know the history. I don’t know whether there are mental illness issues. I don’t know whether he tried to rehabilitate and was pushed in the wrong direction [or] gang affiliation — all the things that we ignore.”

These details will no doubt emerge in the coming weeks. In general, though, there’s not enough money spent on rehabilitation or on trying to address the root causes of crime.

Case in point: Maynor, according to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, didn’t have a permanent address when he was released from prison on Sept. 1 after serving a four-year sentence for second-degree robbery with enhancements for a prior felony. He was on parole.

“But we don’t want to make this the battle cry of the right or the left. There’s work to be done and we need to do the work,” Lawson said. “This is a consequence of not doing that work.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.