The 2,000-pound bomb followed its instructions as it raced through the cold December sky above the small Afghan village of Shawali Kowt.

At more than 1,000 mph, it pierced the northwestern slope of a small hill. Cody Prosser had seen a contrail coming out of the northeast and for a split second heard a roar, then an explosion. His eardrums ruptured.

A wind exceeding a tornado’s strongest gust blew him off his feet as the air around him caught fire. Airborne, he floated through an avalanche of sand and earth. A shard of fragmenting steel struck his head.

He crumpled to the ground.

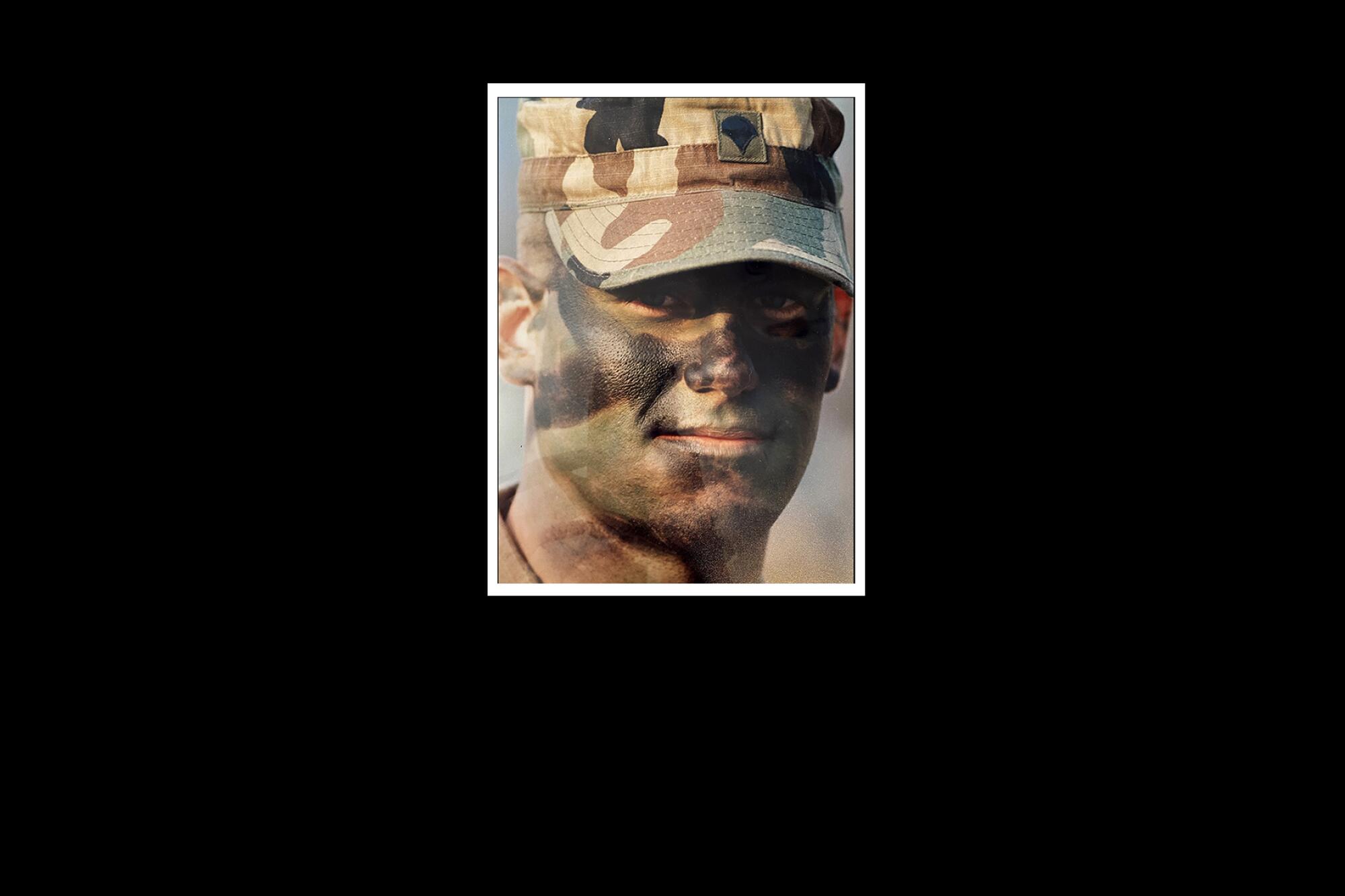

Twenty years later, the life and memory of U.S. Army Staff Sgt. Brian Cody Prosser are still mourned. The first Californian to die in Afghanistan, he lies in Arlington National Cemetery.

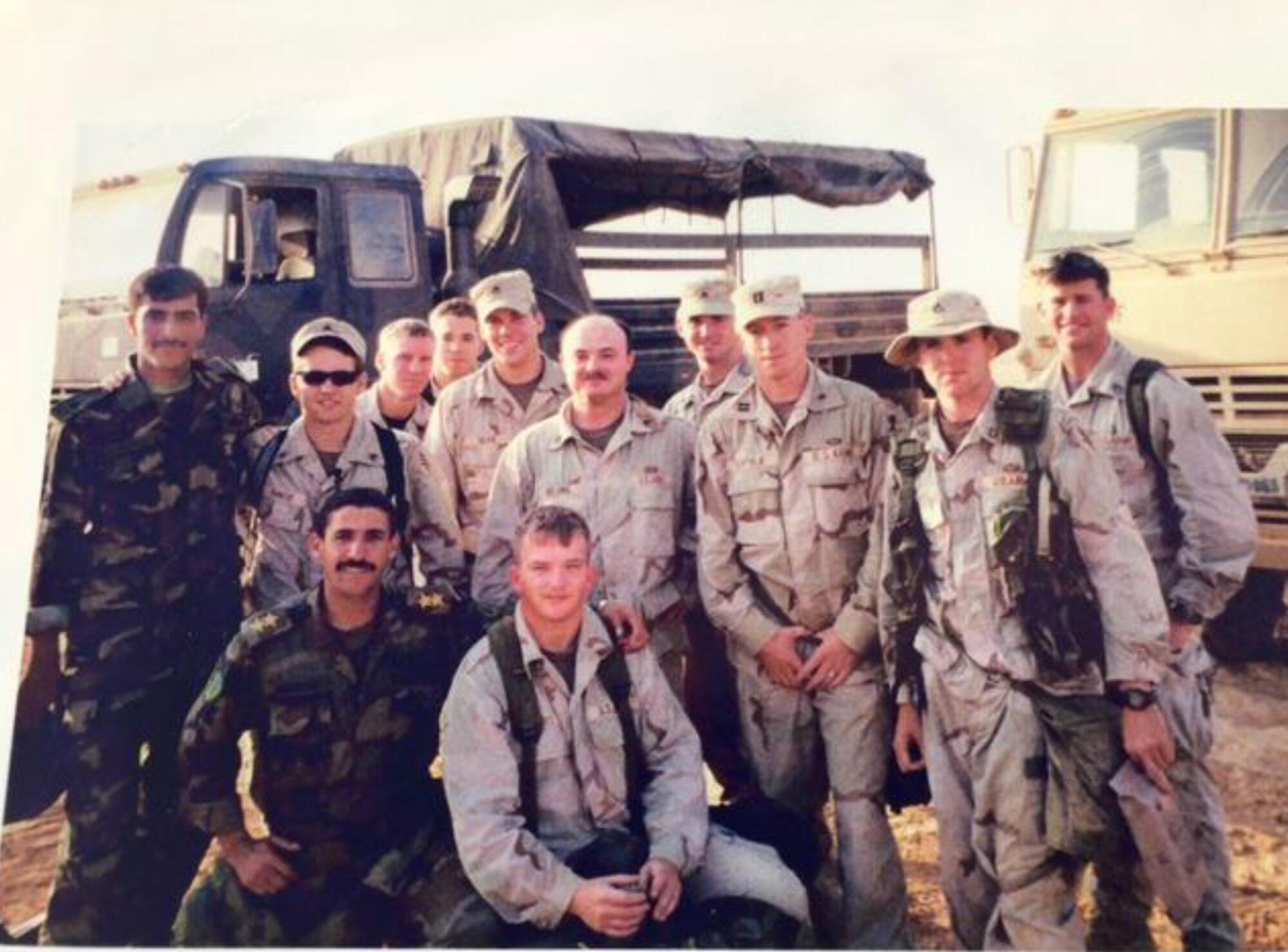

Cody, 28, had boarded a helicopter for a predawn flight into Afghanistan on Dec. 5, 2001. He and 13 other soldiers and airmen from Ft. Campbell, Ky., had been chosen to join a small contingent of Green Berets who had been fighting on the ground for three weeks.

“We must support our nation. We must avenge our brother and sisters,” he wrote to his family not long after the attacks on Sept. 11. “Remember that our nation’s symbol is the eagle. … Different parts of the country make up different parts of this glorious bird. I am proud to say that I stand ready to do my part as I am in an organization that makes up the balls of the eagle.”

Cody’s swagger reflected a moment in American history when the currents of patriotism and belligerence ran together. After his death, his family and friends kept his story and their grief private. Twenty years later, they speak more openly about their loss and the frustrations they have felt as the country’s longest war ground to an end.

The bomb that killed Cody was released from a U.S. Air Force B-52. It had followed its instructions, but those instructions were wrong. Cody died by friendly fire.

“Cody’s death was emblematic of the war to follow,” said Jason Amerine, who stood near Cody that morning in Shawali Kowt. “Soldiers and civilians died, and the war dragged on without the fundamental questions being answered: What are we doing here? What does success mean, and how do we achieve that?”

::

Growing up in Riverside and Kern counties, Cody was a young man whose childhood never suggested the heroics or moral clarity ascribed to acts of bravery. Limited opportunities fostered a rebelliousness that bordered on delinquency.

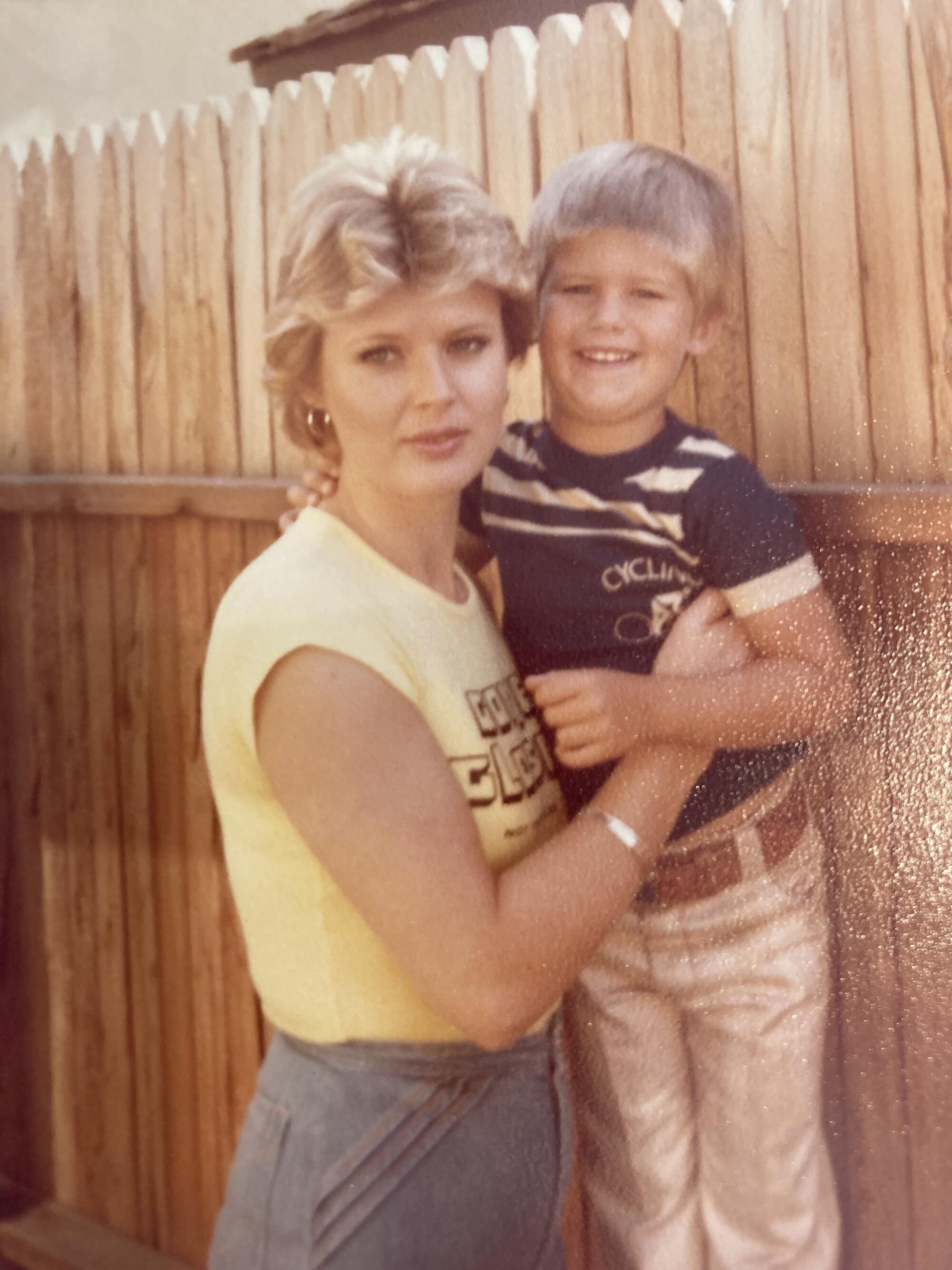

He reminded his mother, Ingrid Solhaug, of Dennis the Menace with his towheaded, blue-eyed charm that could get him out of any jam. She had come to Los Angeles from Sweden to be a model. A few years later, a mother at 24, with an 8-month-old child and separated from Cody’s father, she headed to Bakersfield to work as a waitress.

Money was tight, but Cody seldom let its absence get in the way of what he wanted. Shoplifting was the thrill, candy bars the reward.

When his half sister Lisa Donato was born, Cody, then 7, helped take care of her. She adored him, and Cody and Lisa made the most of their time.

“We used to go next door to the apartment complex when it was being built and pretend we were camping,” she said. “We would build a little fire to heat up some soup — a classic ‘Don’t tell Mom’ moment.”

Their time together ended when Cody, 13, stole $100 from a neighbor. Ingrid, by then living in Indio, knew that she needed help raising him.

“Do you want to live with your father?” she asked.

Yes, he said, and Ingrid agreed. Saying goodbye, she never thought she would feel such pain again.

A college football player who served briefly in the Army before becoming a Los Angeles firefighter, Brian Prosser knew the meaning of discipline. After a career-ending injury, he opened a welding shop, and his wife, Juliana, ran a nail and hair salon next door.

Pops wasted no time putting Cody in his place. After a shoplifting incident in Bakersfield, Cody spent the afternoon confined to a hot car with his brother Jarudd. After another incident, Cody spent the night in juvenile hall.

“That dude was big trouble,” said Ruben Gonzalez, one of Cody’s oldest friends. The two played baseball and football at Maricopa High School. “He could have been a straight-A student if he wanted to, but he loved to get into fights. He was kind of a bully.”

Sports helped channel that energy. Not even a dislocated shoulder could stop him, Gonzalez said.

“Pops would come onto the field, give it a tug, and Cody would be back.”

In 1991, the year the Gulf War ended when American troops drove Saddam Hussein out of Kuwait after 43 days of combat, the fathers in Frazier Park arranged for an Army recruiter to meet a few of the seniors.

The pitch was easy, Gonzalez recalled: “Who wouldn’t want to jump out of planes, shoot guns and get paid for it?”

Profile: Special Forces fighter Brian Cody Prosser of Frazier Park followed his father into the armed services. He died under ‘friendly fire.’

::

Cody’s first assignment was at Ft. Bragg, N.C., where he unexpectedly ran into his old high school friend while working a traffic accident on base. Gonzalez was a firefighter, and Cody was with the military police. Soon they were hanging out together, barbecuing on weekends and swapping stories.

The more Cody shared details of his life, the more Gonzalez appreciated what his friend had overcome: his parents’ separation, raising himself and Lisa while Ingrid worked.

Cody married when he was 21. His wife was a captain in military intelligence, nine years older and with two children. “He always wanted to have a family,” his sister said.

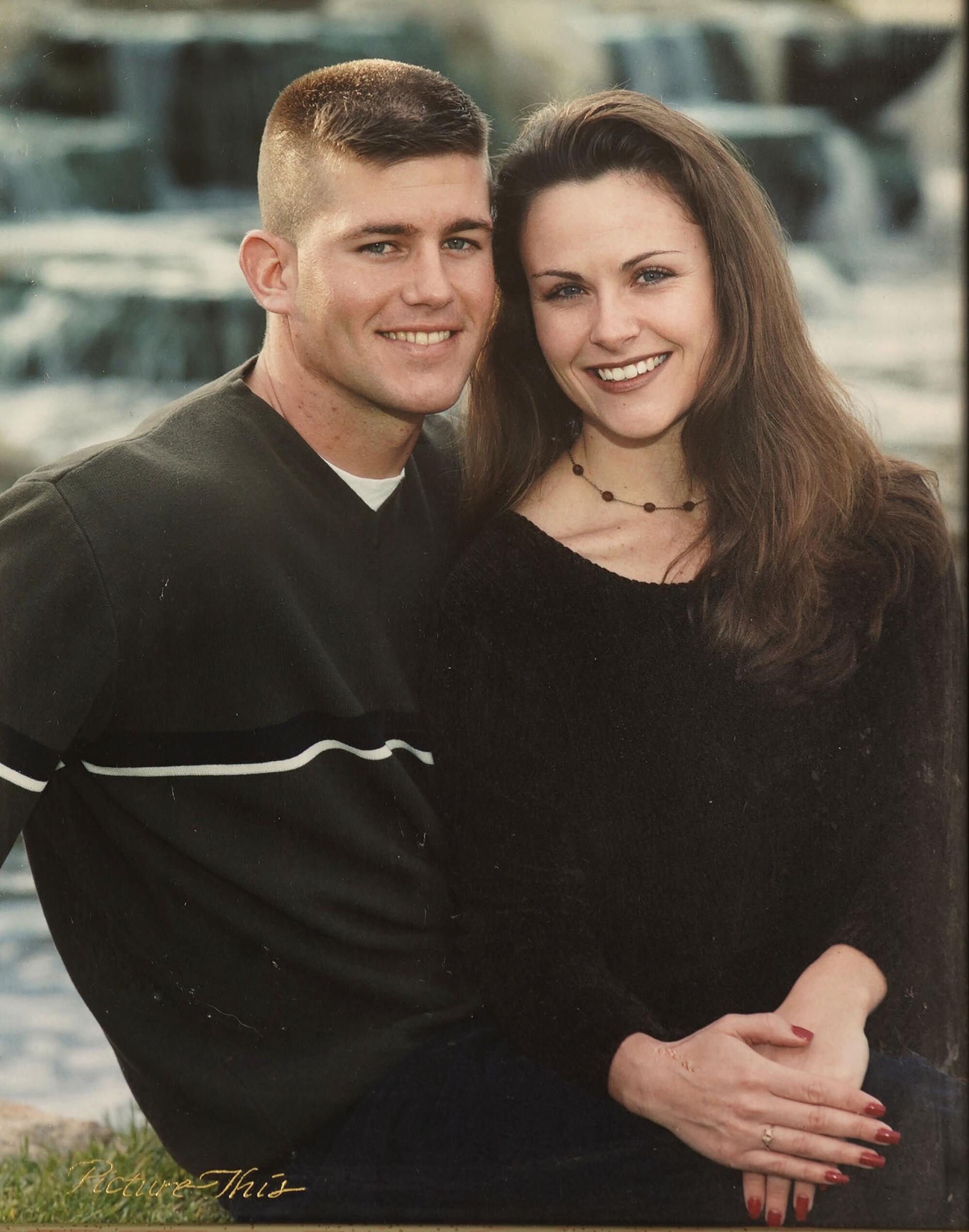

The marriage didn’t last, but Cody had a second chance when he met Shawna Glenn at a honky-tonk in Bakersfield.

He was on Thanksgiving leave from Ft. Huachuca, Ariz., when he saw her across the crowded, smoky bar. She was celebrating her 23rd birthday and was flattered to have a handsome stranger approach her.

“He was very easy on the eyes,” she said, “and he had a great sense of humor.”

They slow-danced to Deana Carter’s “Strawberry Wine” and exchanged phone numbers. They met again the next weekend.

Cody already had been to Somalia and Haiti and had decided to go into intelligence. During his next deployment, a yearlong stint in Korea, he and Shawna grew close over phone calls, letters and a two-week leave in San Francisco.

When she met him at Los Angeles International Airport in early 1998, they hugged, and he knelt down and presented her with a ring and a poem.

Five months later, they were married in Ventura and, by the end of the year, had bought a two-story home in Clarksville, Tenn., next to Ft. Campbell, where Cody was based.

They went to church, got baptized together and talked about starting a family. But Shawna, who taught elementary school, wanted to get a master’s degree, and Cody was overseas as much as he was at home.

“In our five years, we were probably apart more than we were together,” Shawna said.

Showing a focus that eluded him in high school, Cody flourished as an intelligence analyst with the 5th Special Forces Group. A friend described him as a “true believer,” devoted to the mission of Special Forces: De oppresso liber, to free the oppressed.

His job — intercepting and interpreting information about potential enemies — took place against a darkening backdrop of Al Qaeda attacks against the U.S.: truck-bomb explosions at the American embassies in Tanzania and Kenya in 1998 and a suicide attack in Yemen against the USS Cole in 2000.

After the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, Cody spent long hours on base, but one night he and Shawna were cuddling on the couch.

“If anything happens,” he told her, “I want you to know, I want to be buried in Arlington.”

::

Cody shipped out on Sept. 26, 2001, 11 days before the United States and Britain launched airstrikes against Taliban positions and Al Qaeda training camps.

“I don’t know what’s going on. But something is happening, and it sounds very serious.”

— Shawna, wife of Cody

Cody and his battalion arrived in Jordan for a training exercise. At its conclusion, the commander requested 14 soldiers for a mission into Afghanistan. Cody’s senior officer, Capt. Jeff Leopold, didn’t hesitate to recommend an intelligence analyst.

“Cody’s the guy,” he said.

Next stop was Uzbekistan, where Cody wrote Shawna a letter, filled with the wistful loneliness of a soldier reflecting on his life.

“Princess,” he began, “well, today is the first of November, and by now you know that I am not coming home as expected. I was laying here on my cot thinking about how much I miss you. I want you to know how much you mean to me.”

The war was ramping up. Special Forces, fighting alongside tribal leaders on horseback, were pushing the Taliban out of northern districts. CIA officer Johnny Micheal Spann, killed during a prison uprising, became the first American fatality of the war. To the south, U.S. soldiers had joined Pashtun guerrillas opening a second front.

Cody spent Thanksgiving in Pakistan and called Shawna.

“I don’t know what’s going on,” she told a friend afterward. “But something is happening, and it sounds very serious.”

She never heard from him again.

::

Jostling for hours through the night, Cody’s helicopter set down in Afghanistan at 3:45 a.m.

Flashlights, headlamps and high beams cut through dust as soldiers unloaded two four-wheel-drive trucks, piled in their gear and rode 20 minutes to an empty medical clinic where they tried to sleep against the pulse of their racing adrenaline.

Shortly after first light, Cody and his team climbed a small hill the Americans called the Alamo. Scruffy Green Berets mingled among bearded locals armed with AK-47s. The ragged assembly smelled of sweat, camp smoke and weeks of combat.

The threat level was low. Letters were being opened, photos of family shared, treats passed out. Cody and Leopold began to gather information.

Amerine, a captain at the time, was one of the commanders that morning on the Alamo. A fellow Californian, he got to know Cody two years earlier in Kuwait.

“What the hell are you doing here?” he said at their unexpected reunion.

F-18 jets screeched across the sky in a bombing run against a reported Taliban position, a cave complex near a bridge more than a mile away. Smoke plumed into the sky.

Leopold went to get the latest intel on operations in the north and south. The communications team had set up a tactical laptop with satellite phone and antenna. Leopold bent over the equipment.

Then he was hurtling through the air.

::

When the cloud of dirt began to settle, Amerine stumbled to his feet. Shrapnel was buried in his left thigh. Through black smoke and grit, he could see casualties all around him.

Not far away, Leopold came to. His eyes stung from the dust. His ears felt stuffed with cotton. He heard a voice.

“Can you walk?”

Yes, he answered.

“Well, good. There are others who can’t, so get up.”

Leopold helped move the injured off the hill. Shrapnel had shredded legs and arms, opened skulls and chests, severed limbs. Medics had begun writing triage numbers on foreheads.

During an official inquest weeks later, a soldier described the scene.

“If you try and picture it in movies or what you’re trained to in a triage scenario, it was probably 100 times worse than anything I’ve ever pictured, as far as that goes. Highly trained Special Forces people were just sitting there, not able to look or do or just try and comprehend what had happened.”

Amerine saw Cody laid out on the ground. A white bandage circled his head. Amerine initially thought he was fine.

“It looked like he was sleeping,” Amerine said. “He was breathing heavily, and his hands were moving like he was having an intense dream.”

He was in a coma, bleeding internally. The injuries got worse as inflammation progressed.

“I recall walking over to him,” Leopold said. “His head was wrapped up, and he was laying there. I don’t believe he was suffering. I knelt by him and touched his arm.”

The Army estimated that 23 Afghan fighters were killed; unofficial estimates put the number closer to 50.

Amerine lost two of his men: Master Sgt. Jefferson Donald Davis, 39, from Tennessee, and Sgt. 1st Class Daniel Henry Petithory, 32, from Massachusetts.

Hours later, after being evacuated to a forward operating base south of Kandahar, Cody was pronounced dead. Leopold held his hand and told Cody how much he admired him.

“It was hard to say goodbye,” he recalled, “hard to realize that someone I had gotten to know over the last few months was gone, and we’d been unable to save him.”

::

On Dec. 5, Shawna woke up, poured her coffee and read the news online: Three American soldiers dead, no names, no units.

But 5th Group was in Afghanistan, and that would likely bring the tragedy to Ft. Campbell. Because most of her students’ parents worked on base, she braced herself. She expected Cody to be fine — his job had kept him out of combat — but still, she worried.

“If the guys in green show up, don’t send them my way,” she told a friend.

Halfway into a math lesson, she was interrupted by a teacher’s aide. The guys in green had arrived.

“They need you in the front office.”

Shawna barely got into the hallway before hitting a wall and sliding to the floor. She remembers bellowing in pain. The aide rushed to close the door behind her. Other teachers came out and helped her to her feet. They led her down the hall. She felt as if they were dragging her.

The base commander and chaplain met her.

“On behalf of the United States,” the commander began, and Shawna felt her knees buckle.

Cody’s mother had stayed up the night before preparing a care package for her son. She knew he missed his dogs back home, so she had bought him a stuffed Husky, mascot of the University of Washington, where his father played football. She also included a Husky sweatshirt for warmth against the Afghan winter.

Later, she couldn’t sleep, so she decided to pray, and in her prayers, she saw lights that she imagined to be angels. They would keep her son safe, she thought.

“Ingrid,” her husband roused her a few hours later. “Ingrid, it’s Cody.”

She didn’t understand. Then two soldiers were standing in her bedroom. They regretted to inform her that her son had been killed in action.

That afternoon, Ingrid called Cody’s sister, Lisa, who was working at Chili’s in Cypress. The receiver fell out of her hand.

Shawna couldn’t reach Cody’s father but called one of his brothers who lived in Bakersfield. He got hold of the elder Prosser, who called Jarudd.

“Hey, Pops, what’s up?” Jarudd remembers asking.

He had never heard his father cry.

By the time Jarudd got to Lockwood Valley, the family home was crowded with friends and neighbors.

Then two soldiers from Ventura drove up in a white car.

::

Cody’s story became the nation’s story.

When Shawna turned on the television, she saw her husband’s face along with those of the two other soldiers who had been killed. Following instructions from the base, she kept away from the media, turning down an invitation to talk with Katie Couric on the “Today” show.

The Seattle media tried to reach Cody’s mom. They invited her to their studios, but she wasn’t ready.

Lisa also held her memories close.

“I didn’t want to talk to reporters,” she said. “Cody was the most important person for me growing up.”

Meanwhile, in Lockwood Valley, the Prossers found themselves surrounded by media vans. The following day, Cody’s father spoke publicly about his son.

“I just want to say we are extremely proud of him,” he told reporters from the porch of his home. “He is a hero in our house, and I hope in your house, too.”

Cody’s family knew that the media wanted to address the fact that he had been killed in friendly fire.

“There is no such thing in this house as friendly fire. Fire is fire,” Cody’s father said. “Those guys were there to do a mission.”

In the days that followed, Prosser and Shawna often spoke. They agreed: No one was at fault. The bombing was just a terrible accident.

“I didn’t know the details,” she said. “But I wasn’t naive. I know that when you go into a situation like this, there is chaos and confusion, and mistakes will happen.”

She also knew that Cody would have nothing to do with any second-guessing.

“Had he known what he was in for,” she said, “he would have done it anyway.”

Two years later, U.S. Central Command issued a lengthy report, citing “fatigue, frustration, distraction and overconfidence” as factors leading to the tragedy.

But there was more.

Shortly before the bomb was released, new batteries had been placed into the GPS targeting system. That action deleted the coordinates of the cave and reset the coordinates to a few meters in front of the GPS.

::

Laid out in a casket, dressed in his Army green Class A uniform, Cody was memorialized in two ceremonies. The first drew nearly 1,000 people to Hillcrest Memorial Park in Bakersfield, where, at a private viewing, Ingrid kissed her son goodbye. Lisa slipped into his pocket a ring shaped in the symbol of the Sanskrit word Om.

“I wanted to give him something to take with him,” she said.

Later, family and friends left mementos in a niche at the Court of Honor: a picture of Cody’s dogs, a baseball he had hit over the fence in high school, a parachutist badge recognizing a jump taken at Ft. Bragg and a letter with the wish that “things could go back to the way they were.”

The next day, Cody was flown to Washington, D.C., and transferred to Arlington National Cemetery. Ingrid’s brother had brought red roses to the interment, and Ingrid handed one to Shawna, who held tightly to her father’s arm before giving in to the sorrow of a final goodbye.

In the distance, three soldiers, wrapped in white blankets, watched from their wheelchairs. They had been with Cody that morning in Afghanistan.

Cody’s funeral was among the first of nearly 7,000 for American service members who died in Afghanistan and Iraq. The unity forged in the aftermath of 9/11 faded into a stubborn commitment that cost the U.S. trillions of dollars and left hundreds of thousands dead worldwide.

Shawna remarried, and she and her husband, a Green Beret who left the Army after three tours in Iraq and one in Afghanistan, moved away from Ft. Campbell. They have a teenage son and a daughter and have adopted a granddaughter whose mother died of a fentanyl overdose.

In the face of tragedy, Shawna turns to her faith.

“All I can do is pray,” she said, “drop down on my knees and give it up to God.”

For Ingrid, who lives in Rancho Mirage, the memories of those first years after Cody’s death are especially vivid.

“I looked at the world, and everything went around,” she said. “How could people talk or smile? I could barely breathe. I couldn’t move.”

The pain, still so visceral, sometimes catches up with her and is hard to put into words. She knows no one will ever understand how she feels.

Lisa feels her brother’s absence in her life daily. Some days are filled with more memories than others, “but now it’s a little easier to smile at them rather than cry.”

Jarudd’s sorrow was compounded two years later, when Brian Prosser died.

“I went through all the emotions,” Jarudd said. “Angry, then sad, then smiling at the memory of something fun, all in the course of a half-hour.”

Emal Salarzai helped teach elite Afghan troops. Now his parents are on the run from the Taliban, and he can’t find any way to aid them in escaping.

Gonzalez still holds his friend close. Last year on Dec. 5, when his son brought home a pit-bull mix, there was no question what to name the dog.

“Kodi,” Gonzalez said, “because there will only be one Cody in my life.”

Every day, Leopold wrestles with the memory of that morning in Shawali Kowt and wonders how it might have played out differently.

“Maybe I would have died if Cody had been the one to reach for the laptop,” he said. “I still struggle with that, that butterfly effect kind of thing.”

Leopold, who lives in Texas, keeps a piece of shrapnel from the bomb on his desk. On Sunday, the 20th anniversary of the bombing, he plans to visit Arlington. He wants to introduce his 16-year-old son to his friend.

::

Grief is a lonely experience, said Amerine, who retired from the Army in 2016. People gather around, but everyone must handle loss in their own way.

If 20 years have eased the pain, the last six months have only reawakened it.

Watching Afghanistan fall back into the control of the Taliban, Amerine considered the “insane symmetry” between the start of the war and its end.

He didn’t see the need for a bombing run that morning and believes the Army never adequately addressed why it took place. Recent scenes from the airport in Kabul reawakened “all the tragedy and stupidity” of that day in 2001.

The American mission in Afghanistan deserved a better ending, he said.

Watching events from her home in Tennessee, Shawna also felt the limitation of America’s intervention.

“You dream that you will bring in change, but the change will not be what you want it to be,” she said. “Now we’re left wondering what will happen to our allies, to those who helped us. It is heartbreaking.”

Shawna doesn’t want to believe that Cody died in vain, but the scenes of the American withdrawal, the chaos on the streets and the Taliban’s suppression of women have shaken her.

“I feel for Cody and the soldiers and families who sacrificed so much to do something good in the world and make a change,” she said. “Perhaps everything they did was in vain.”

Cody’s mother still regrets signing the paperwork that allowed her son to enlist before his 18th birthday. Waiting just a few months might have kept him alive. In a memory box in her closet, she keeps his baby rattle, cowboy boots, Winnie-the-Pooh PJs.

“Of course I think his death was in vain,” she said. “My son is dead.”

Leopold rejects the notion that Cody died for nothing.

“Times have changed; situations have changed,” he said. “But that doesn’t change the impact those individuals had in making lives over there better, if only for a short time. I don’t think anyone who lost their life in Afghanistan would say they died in vain. They died believing in what they stood for.”

::

Memory and grief, now reawakened, will once again lose their sharp edges. The passage of time has already transformed the past.

At Ft. Campbell, a sugar maple planted in Cody’s honor is no longer a sapling. In Frazier Park, the flags that encircle the stainless-steel memorial to Cody are wind-whipped and tattered. At Green Hills Memorial Park in Rancho Palos Verdes, the bronze finish to the statue of St. Michael the Archangel standing beside a marble monument honoring Cody is slowly aging.

At Ft. Huachuca, soldiers are housed in barracks at Prosser Village without knowing its namesake’s full story. In Bakersfield, Cody’s uniform, placed in a shadow box by his father, hangs in the entry hall of his older brother’s home. At Arlington, Grave No. 7186 is more weathered.

Honored with a Bronze Star for valor and a Purple Heart, Staff Sgt. Brian Cody Prosser is interred near a row of ginkgo trees not far from a memorial dedicated to those who perished in the 9/11 attack on the Pentagon.

Like the other veterans beside him, Cody holds formation in death as in life.

::

This report is based on telephone interviews with Cody’s widow, Shawna Blue, and her friend Dawn Johnson; Cody’s mother, Ingrid Solhaug, and sister Lisa Donato; Cody’s stepmother, Juliana McMurtrie, and his half brothers, Jarudd and Reed Prosser; his friends Jason Amerine, Jeff Leopold, Ruben Gonzalez, Patrick Horton, Stan Lavery and Richard Walker; bomb blast expert Ibolja Cernak at Mercer University; neurotrauma expert Christopher Giza at UCLA; and Eric Blehm, author of “The Only Thing Worth Dying For: How Eleven Green Berets Fought for a New Afghanistan.” Additional reporting came from the 2003 redacted and unclassified “Report of Investigation” by the U.S. Central Command.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.