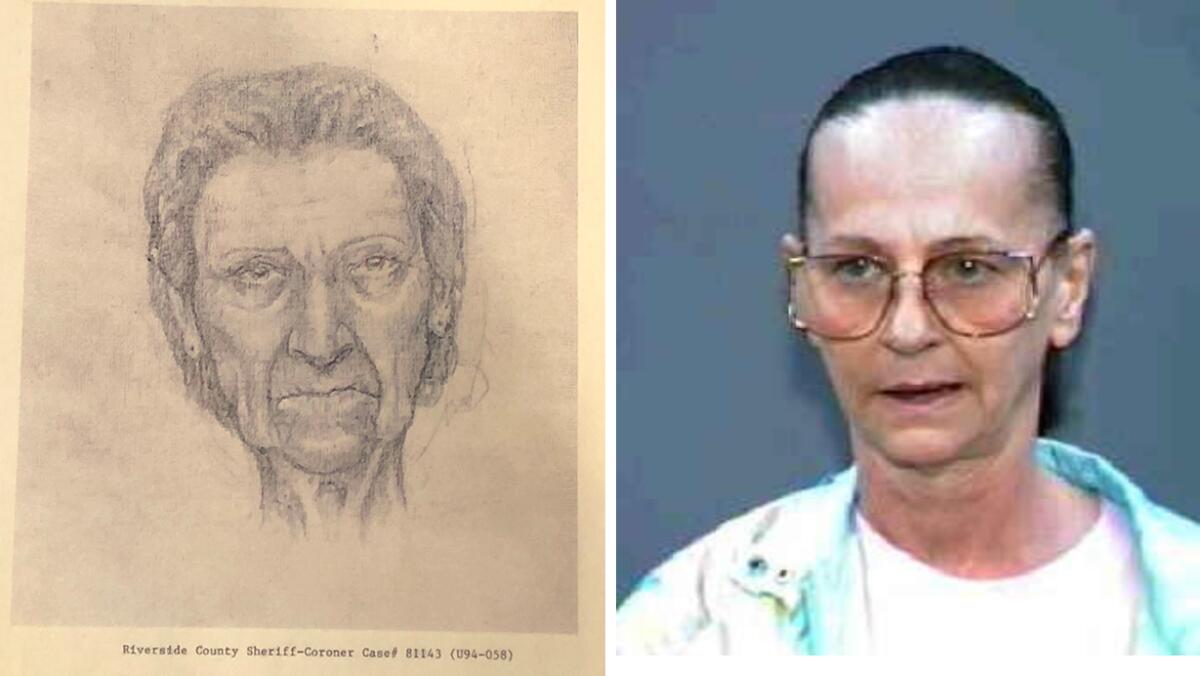

Cold case victim from 1994 is identified through forensic genealogy in Riverside County

- Share via

After nearly 30 years of languishing in anonymity, the victim in a 1994 cold case death has been identified through forensic genealogy, authorities in Riverside County announced this week.

Forensic genealogy, a relatively new investigative tool, involves uploading DNA into public databases to look for family members or matches.

The long saga in Riverside County began Oct. 24, 1994, when the body of a woman — now known to be Patricia Cavallaro, 57 — was found partially buried in the Thousand Palms desert, the Riverside County district attorney’s office said in a news release.

Investigators used “all available resources at the time” to identify the woman, including entering her DNA into the California Department of Justice’s Missing and Unidentified Persons System, but no match was made.

The investigation was eventually taken over by Riverside County’s regional cold case homicide team, which includes members of the district attorney’s office, sheriff-coroner’s department, police departments and the FBI.

After a 79-year-old woman was raped in her own home, genetic genealogist CeCe Moore had to work fast.

Last year, the team had a DNA sample created for the purposes of forensic genealogy. The sample came from one of Cavallaro’s bone fragments, supervising investigator Ryan Bodmer said.

Using genetic matches, they found a biological child — a son — who then provided his DNA sample to the state for official confirmation.

In mid-December, the Department of Justice verified that Cavallaro was the victim in the 1994 death. She was born March 22, 1937.

“Building a family tree opens the door to possibilities and leads that our detectives would’ve never had, whether it be a victim or a suspect,” Bodmer said, noting that “genealogical solves” represent about 12% of his team’s cold case resolutions.

Bodmer said the manner of Cavallaro’s death was “homicidal violence,” but determining the exact cause will be challenging.

Her husband filed a missing person report in 2001 and has since died, he said.

There was no match in the FBI’s national DNA database.

In 2018, the field of forensic genealogy made national news when investigators tracked down Joseph James DeAngelo Jr. — known as the Golden State Killer — through the genes of his great-great-great-grandparents. DeAngelo had evaded authorities for decades.

The approach is “fraught with ethical questions,” The Times wrote, noting that it works at the intersection of law enforcement agencies, private-sector companies and the personal information that such companies have amassed from their customers.

Bodmer said most large genealogy services, including 23andMe and Ancestry.com, are very restrictive toward law enforcement access, but users are able to upload their DNA to other, free services or in some cases opt in to allowing their information to be shared.

County officials said the practice was a game changer in solving Cavallaro’s case.

“Without the use of forensic genealogy, this victim may have never been identified,” they said.

Though Cavallaro’s son wishes to maintain his privacy, Bodmer said the coroner’s office is working with him to conduct a proper burial with a headstone — finally, after all these years, “giving her a name.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.