Lawmakers move to tighten restrictions on sex-offending doctors

- Share via

Doctors who are convicted of sexually abusing patients would be permanently banned from practicing medicine in California under a bill introduced this week by state legislators.

The move comes a month after a Times investigation found that the Medical Board of California had reinstated 10 physicians since 2013 who lost their licenses for sexual misconduct. They included two doctors who abused teenage girls and one who beat two female patients when they reported him for sexually exploiting them.

The Medical Board of California was established to protect patients by licensing doctors and investigating complaints. The board has a long history of going easy on troubled doctors, a Times investigation has found.

“I read that article and my stomach turned. This is the sort of stuff you see in horror movies,” said the bill’s lead author, Assemblywoman Akilah Weber (D-San Diego), who is an obstetrician/gynecologist. “I was shocked. I was very concerned for patients and very concerned for the medical profession itself.”

The measure would be a major overhaul of current practice, which patients and healthcare advocates contend favors leniency for doctors and provides victims of sexual misconduct no voice in the disciplinary process.

The change would take the decision to reinstate such doctors out of the hands of the Medical Board and “make it very clear that this is something we will not tolerate in California,” Weber said.

Under the bill, any doctor who is criminally convicted for sexual misconduct with patients — as were several in The Times’ investigation — would lose their license and be prohibited from applying for reinstatement.

The bill faces little known opposition and is backed by the California Medical Assn., the politically powerful doctors’ lobbying group that patient advocates have long accused of obstructing reform and shielding bad physicians from disciplinary action.

In a statement Thursday, the CMA said the bill would ensure that “physicians who commit this egregious conduct are appropriately disciplined” and would protect “the integrity of the medical profession.”

Also on Thursday, Medical Board president Kristina Lawson said “we welcome and we’re grateful for the introduction of this bill,” adding that “the patient-doctor relationship is one that’s based on trust. Any doctor who breaches that trust through sexual misconduct or otherwise should not be able to continue practicing medicine in California.”

Assemblyman Al Muratsuchi (D-Rolling Hills Estates), a co-author, is a former prosecutor for the state attorney general’s office who worked on cases involving doctors accused of sexual misconduct. He condemned the “glaring loophole” in current state law that allows for reinstatement.

“There really is no excuse,” Muratsuchi said. “This bill is a long overdue, common sense proposal to protect patients from sexual misconduct.”

Currently, when a physician is charged with sexual misconduct, the medical board usually waits to act until the criminal case is resolved. Board lawyers have argued that attempting to revoke a doctor’s license while the case is still pending is difficult and could ultimately interfere with the prosecution.

If the doctor is found guilty, the board usually then revokes the license or allows the doctor to surrender it.

But even in those cases, under current law, the doctor is eligible to apply for reinstatement three years later.

The board has wide latitude when considering those applications, even in cases of severe misconduct such as physically assaulting patients, sexually abusing minors or lying to police.

The board reinstated Bakersfield internist Esmail Nadjmabadi in 2015, six years after he pleaded no contest to a criminal charge of sexually exploiting patients. Six women — including one in her mid-teens — had told authorities about their abuse at his hands.

He abused Fabiana Ramirez Flores on the pretext of screening her for colon cancer. She was an undocumented immigrant and, when she spoke up about the abuse, Nadjmabadi reported her to immigration officials in a bid to make her “unavailable” to investigators, according to Medical Board records.

He also persuaded a female staff member to lie to police about being in the room during one of the assaults, according to an accusation filed by the Medical Board.

“I don’t know how they can return a license to someone like that,” Ramirez said after learning of Nadjmabadi’s reinstatement from a Times reporter. “He was taking advantage of vulnerable women.”

Nadjmabadi declined to answer specific questions about the case, saying, “That’s ancient history; it’s over. I’ve moved on with my life. Life is good.”

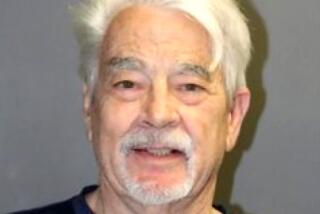

The board also reinstated Dr. Zachary Cosgrove, 57, a Bakersfield family practitioner who had sex with three female patients, then turned violent when they reported him to authorities, according to the Medical Board accusation. He kicked and punched one, threw furniture at another and told the third, “You’d better just kill yourself. ... That’s going to hurt less than what I’m going to do to you,” the accusation states. Cosgrove admitted to the allegations as part of his petition to be reinstated.

“He knew that I was vulnerable,” the woman, who asked to be identified only by her initials T.T., told a Times reporter in a recent interview. “He knew that I was depressed, and I was taking antidepressants, and he said for me to kill myself,” she recalled. “Who does that?”

Cosgrove surrendered his license in 2008 and the board turned down his initial request for reinstatement three years later. But they reinstated him in 2016 after he explained that his behavior had been driven by an addiction to methamphetamines that made him “hypersexual.”

In a brief interview, Cosgrove said he “absolutely” deserved to get his license back. “I went through a lot of rehabilitation,” he told a reporter. “I think second chances are a good thing.”

Nothing in current state law required the Medical Board to approve the applications for reinstatement from Nadjmabadi, Cosgrove and others.

In fact, administrative law judges who weighed the evidence in Cosgrove’s applications advised the board not to reinstate him. But the board, a majority of whose members are doctors, voted to overrule the judge the second time around.

Lawson has argued the board’s hands are tied in some cases by bad law and complicated regulations.

The bill comes on the heels of the board asking lawmakers last week for more modest reforms to help it discipline bad doctors, including lowering the standard of proof necessary to prove cases.

In an 11-page letter sent to Legislative leaders, board officials also called for increasing the waiting time for physicians to petition to reinstate their revoked licenses. They also asked that doctors’ licensing fees be increased, the board’s primary source of revenue.

Patients, consumer advocates and some legislators have long contended that the board too often sides with doctors in disciplinary cases and fails in its primary mission to protect the public.

“I think it’s a good start,” said state Sen. Melissa Hurtado (D-Sanger), another co-author of the bill. But it does nothing to address the problem of doctors who are so bad at their jobs that they repeatedly harm patients, with no effect on their licenses.

In July, The Times found that the board had consistently allowed doctors accused of negligence to keep practicing and harming patients, at times leaving them dead, paralyzed, brain-damaged or missing limbs.

“At what point does it become unsafe for doctors to continue practicing, that’s what I’m most concerned about,” Hurtado said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.