You’ve noticed it, right? There’s just something about L.A.’s light

Los Angeles is a place of lights galore — neon lights, klieg lights, headlights, makeup-mirror lights, red traffic lights to turn right on and to run right through.

And then there is … light — the light, the overhead halo of blue, sometimes blanched into whiteness, sometimes edged with smog-sepia. But always, a Goldilocks light, not too hot, not too cool, almost as changeless as if it had been painted up there.

Whatever considerable ugliness goes on here below, there it is. The ocean may churn, the land may quiver, but there’s the unshadowed sky. An Englishman here, accustomed to weather as his conversational gambit, would have to pick another topic.

Southern California’s painters across two centuries, Marion Wachtel to David Hockney, have spent the whole blue palette on it. Julius Schulman’s architectural photographs made the light as top-billed a performer as the buildings. And movie people could not get enough of its consistent uniformity. It made L.A. the phototropic movie capital.

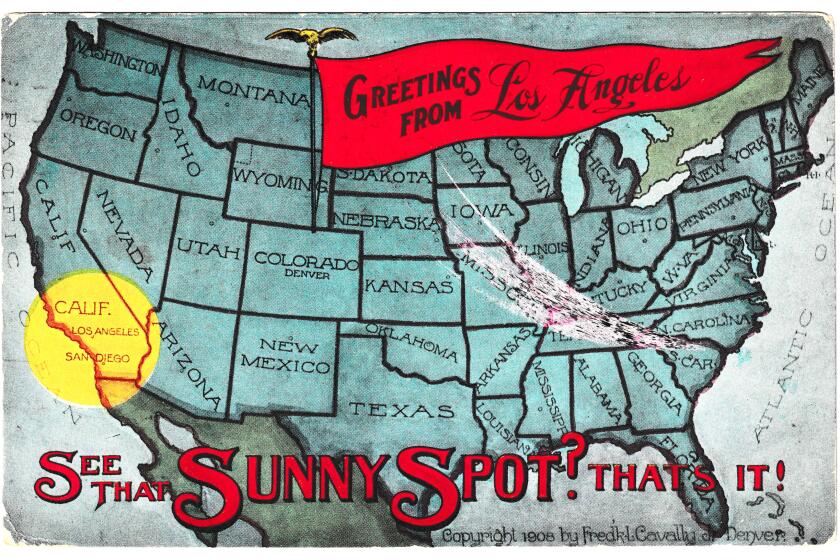

Francis Boggs, actor, silent film director and West Coast manager of the early film company Selig Polyscope, once told The Times that “we find that Los Angeles is the best spot to make our pictures” because “the most essential of all is the sunlight. It is as nearly perfect as can be had, for our work must have the very best of sunlight.”

In those early silent days, the pioneering cinematographer Billy Bitzer noticed something about the silent star Mary Pickford during a break in shooting. The sun was lighting up the white gravel at her feet, which blotted out any shadows on her face. Bitzer reproduced the effect on film.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

In 1916, at Universal City in the Cahuenga Pass, where silent pictures were made outdoors in front of paying audiences, the photo department put an expert up in a crow’s nest atop a lofty mast to keep a literal weather eye. When the light looked perfect, he flew a white pennant to signal “all clear” to directors and cameramen on the stages below, and when light began to look iffy, he sent up a different flag that read, in huge letters, “DON’T SHOOT.”

In 1946, the liberal author Carey McWilliams delivered one of the earliest serious and unsparing analyses of this place in “Southern California Country: An Island on the Land.” No one has accused McWilliams of boosterism, yet this native of Colorado’s high mountains found that “…the charm of southern California is largely to be found in the air and the light. Light and air are really one element: indivisible, mutually interacting, thoroughly interpenetrated.”

More than 40 years thereafter, the L.A.-born writer Lawrence Wechsler, writing “L.A. Glows” for the New Yorker, recalled watching the 1994 O.J. Simpson freeway chase in a cascade of tears — not for the drama, but for that certain afternoon light, the light “I’ve been pining for every day of the nearly two decades since I left Southern California.”

It’s the light Vin Scully evoked to listeners whenever Dodger Stadium cupped the sunlight and the twilight in its hilltop bowl. Toward evening, Scully told Wechsler, with the rim of mountains beyond the rim of the stadium, “it can get to be like a Frederic Remington or Charles Russell painting.”

Sunny and mild L.A. winters have long been used to sell our town to frigid Midwesterners and Easterners, attracting the sick, the farmers and the moviemakers.

Early in the 20th century, mile-high Mt. Wilson was an ideal spot for telescopes that discovered the galaxies, because the air had a pure stillness to it, and while the air remains stable, the quilt of urban light at the feet of the mountains has turned the dark into day.

This limpid air is not everyone’s idea of marvelous. It can have the unsettling feel of a clockless casino; time seems not to pass when every day’s daylight is the same on the sun’s 180-degree transit from desert to mountains to ocean. William Faulkner, the novelist living in sulky exile here to make money writing for movies, longed for the sturm und drang of Mississippi people and Mississippi weather. Writing in 1934, he bewailed L.A.’s air as having “a kind of treacherous unbrightness.”

How, then, can the L.A. of unrelieved light be also the L.A. of noir film and fiction? Dashiell Hammett’s detective Sam Spade did his shamus business in the fogs of San Francisco, but Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe made L.A. the noir capital. I think Marlowe wins; the shadows are so much darker here because the light is so much brighter.

James M. Cain’s was the cool, assessing eye of the writer of “Double Indemnity” and “The Postman Always Rings Twice” — the “poet of the tabloid murder” is what one literary critic called him. And here is what he had to say about the light that suffused the settings he put to paper:

“The main thing to remember is the sunlight, and the immense expanse of sky and earth that it illuminates; it sucks the color out of everything that it touches, takes the green out of leaves and the sap out of twigs, makes human beings seem small and of no importance. … Sunlight gives everything the unmoving quality of things seen in a desert.”

Cain came to L.A. as a grown man, to write for the movies. In the late 1950s or early 1960s, Richard C. Flagan came here as a little boy from Michigan, visiting Disneyland and parts adjacent with his family. “We were here two weeks, never saw a shadow because that was the era of really bad pollution. But I got an incredible sunburn. I swore I’d never live here.”

Well, so much for that. He’s been at Caltech for more than 40 years, where he is now professor of chemical engineering and of environmental science and engineering, and a constant student of how particles and molecules behave in the atmosphere to give us what we love to call Mediterranean light.

The way the sky looks — bluer, whiter, browner — is “the result of scattered sunlight, sunlight scattered by molecules.” And you add in the particles, from the smog, the dust, the exhalations of the earth and the living things on it, the particles interplaying with sun deliver to our eyes the version of light and color that we see.

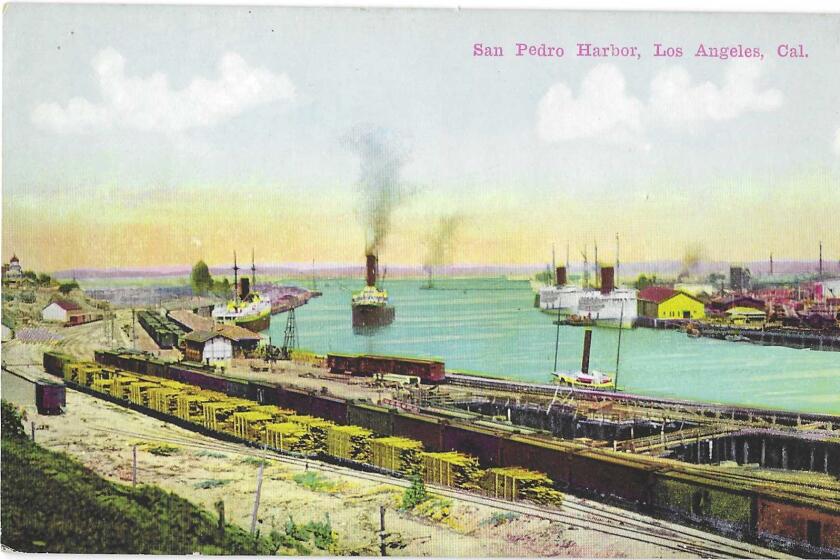

When you think about it, it doesn’t make much sense for 1890s L.A. to put its port all the way in San Pedro. This is the story of how that came to be — and not the competing alternative, Santa Monica.

The really small particles “scatter light over the solar spectrum. The purple mountains’ majesty? What you’re talking about is the particles that are scattering light between you and the mountains … so you are seeing the light reflected off the mountains plus the scattered sunlight from these little particles in the air.”

Now, “if all you had was the sun, and the only scattering of light was from [the sun’s] gas molecules, you’d be looking long distance at an enhancement of the blue and a washing-out of the other colors. When you put [earth-generated] particles in, the particles are scattering light of all colors, but the blue end of the spectrum scatters more than yellow and red. That’s going to wash out the contrast … it would make [the light] seem consistent. It would reduce the contrast.”

Cain “described it as a sort of flatness; I think that would be an apt description.”

And the chief ingredient in the “recipe” for those fancy sunsets of ours isn’t just hot-weather smog. In fact, some of the best sunsets appear in the winter, when a damp wind can broom away the grosser air.

What we see in a sunset, says Flagan, is the effect of the light “coming through a much longer depth than when the sun is straight overhead. At a long distance, you have a lot more cumulative scattering. The blue light is scattered more than the other colors so more red remains,” which accounts for the flamboyance of the sky.

You can test it all yourself, he says. “As the sun is beginning to get lower, stand with your back to the sun and look at the sky. Now turn around — don’t stare straight at the sun, but look in the general direction. When your back is toward the sun, the sky has much more of the blue color than it does when you face toward the sun; that has much more of the reddish color, or you get more of the white haze.” It’s all because “the way the particles are scattering the light from the sun that gives us the distribution of color in the sky.”

It’s a good thing that we have the Los Angeles daylight to rhapsodize over. Our sunsets may hang on in the sky like a painting dangling from a nail, not for us the lingering twilights, the “heures bleues” of elsewhere. Here, the sun can drop into the water like a nickel into a gumball machine, like a nickel into L.A.’s earliest Kinetoscope machines, in a parlor on Spring Street downtown, 125 years ago.

L.A. is a place like no other. You’ve got questions. Patt Morrison probably has answers and can definitely find out.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.