Column: Extremists are set to take over this California county. Will more of the state be next?

- Share via

REDDING, Calif. — When conservatives fight one another over God and country, my general reaction is — have at it, and where’s the popcorn?

But the recent recall election in Shasta County that pitted a Republican ex-police chief against a far-right faction backed by a local militia is different. It’s a wake-up call ahead of the 2022 midterms that elections can go very wrong, even in liberal California.

What happened in Redding should be a big, blinking warning light to what’s left of the mainstream Republican Party, and to us all that we have an obligation as Californians to protect elections across the state, not just the ones in our backyard.

The far right has made it clear that it hopes to target and drive out elected officials in places where their small numbers have outsized power with the right mix of discontent, propaganda and money. If those officials are replaced by ones willing to put ideology ahead of rules and democracy, we are going to end up with actual election fraud (not the conspiracy sort), school curriculums straight out of the 1950s, and perhaps even sheriffs and district attorneys more interested in power than law.

That all may sound alarmist, but as Christopher Browning, a professor emeritus at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and an expert on Nazis and the Holocaust, told me, there’s a certain set of the far right that actually did learn something when they raided Congress a year ago.

Violent takeovers are hard. “Legal revolutions” are easier and more effective.

“They realize that you can’t go out and storm the Capitol, but you can take town hall after town hall,” Browning warned. He pointed out that this tactic has been used by authoritarians before, including in Nazi Germany.

The recall attempt in Shasta has the veneer of a free and fair election, but there’s slime under the surface. Like much in politics these days, it was the pandemic that shook the fault lines open and exposed the ugly in Redding. It started with the shutdown and masks in 2020.

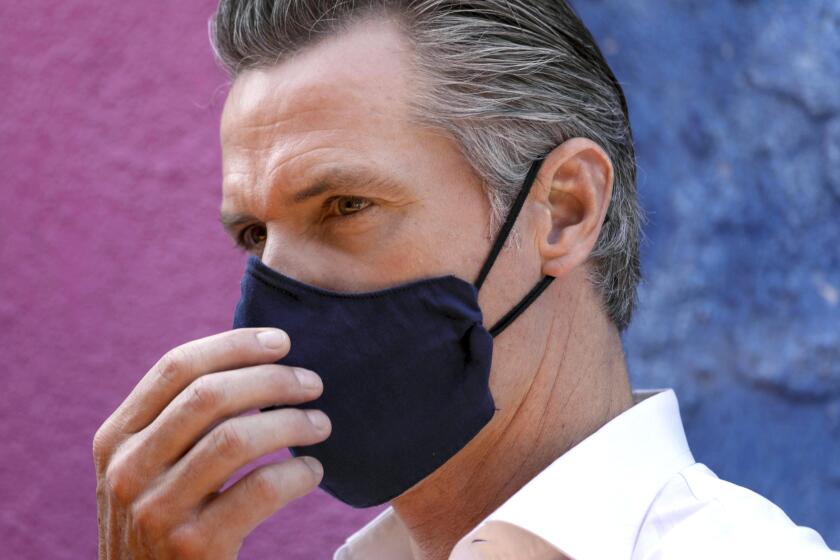

Though the five members of the county Board of Supervisors had no particular interest in enforcing Gov. Gavin Newsom’s mandates, widely unpopular here, the majority of them didn’t rant and rail against them, either. So while most of Shasta County went about life, with businesses remaining open and mask rules enforced only in the loosest sense, a contingent of the outraged began showing up at meetings, charging their elected officials with “bowing down” to King Newsom.

In a turbulent 2021, more recalls fell short than succeeded, a reversal of the usual trend.

Meetings turned into carnivals, not the fun kind, with speakers threatening violence, and someone got the idea to recall three supervisors who were deemed too liberal and scientific in their approach to the pandemic.

The Cottonwood militia, an armed group of men who describe themselves as civic leaders and helpers of local law enforcement (though law enforcement has said they are not affiliated), threw their might into the effort. A film producer, best known for religious music videos, decided to make a glossy documentary full of slow-motion horseback riding about it, hopeful a successful recall would provide a blueprint for other communities to do the same.

A Shasta County supervisors’ meeting was faced with verbal threats to government officials and talk of civil war. “You have made bullets expensive. But luckily for you, ropes are reusable,” one person threatened.

They started a podcast and spent a lot of time telling one another (and anyone listening) how important they were to saving Shasta from what they described as criminal corruption — something they argued could be punishable by death. They demanded a government beholden to nothing and no one, except themselves, quoting dubious interpretations of the Constitution. Eventually, organizers collected enough signatures to trigger an election to unseat one supervisor, Leonard Moty, Redding’s ex-police chief who describes himself as a fiscal conservative and social moderate.

The fight seemed neck and neck for a while until money came in the mix. Reverge Anselmo, the son of a billionaire and an erstwhile film producer and director, began dumping thousands into the recall effort, though he lives in Connecticut. It was $50,000 at first, then $400,000 in November. I left a message with Anselmo’s assistant but never heard back as to why he funded the far-right campaign. Local media reported that he had a beef with the county over permitting on a vineyard and restaurant he tried to build there.

The money put the recall in overdrive, with ads bombarding voters on radio and television. Doni Chamberlain, a local journalist, said regular Shasta residents were pulled into the rhetoric, and became “dupid.” That’s a mash-up of duped and stupid.

“It’s that thing,” said Chamberlain. “If you say something long enough and often enough, people will believe it.”

The election was held Tuesday, and while some ballots are still out, it is almost certain Moty will be recalled, leaving Shasta County likely to have leadership that is beholden to the militia and their far-right compatriots. For months, militia members have been clear about what that looks like.

“We have to make politicians scared again,” Carlos Zapata, a bar owner and militia member, told my colleague Hailey Branson-Potts, as the militia was heating up its tactics. “If politicians do not fear the people they govern, that relationship is broken.”

It isn’t just politicians who are cowed. Regular citizens are, too. People came up to Moty and said they supported him, “but they didn’t want to have their name out there because they are afraid,” he said.

It was safer to be quiet because those who opposed the recall, along with county employees deemed problematic, have received death threats and had their home and work addresses posted online. (Recall supporters say the same has happened to them.)

The official in charge of elections was recently “served” with papers accusing her of treason, and threatening a death sentence. Nathan Pinkney, a recall opponent who created a fictional social media character named Buford White to mock Zapata, was attacked by Zapata and two friends, in an altercation where a witness said the N-word was used. Zapata was found guilty of disturbing the peace by fighting and sentenced to community service, probation and an anger management class.

Moty, who spent three decades in law enforcement including six as chief of the Redding Police Department, has been threatened, accused of being a pedophile, of taking bribes, of colluding with voting machine maker Dominion Voting Systems to defraud the election, being against the 2nd Amendment (a big insult in these parts) and more, he told me Wednesday.

His wife, Tracy, whose family has lived in Redding for four generations, was so stressed, talking about the recall campaign made her cry, and she decided to go sit in her car rather than relive the details in an interview. The couple are thinking about moving, because Redding has changed in ways that don’t feel right to them. Tracy said she doesn’t feel safe.

Moty tried to get help from Republicans and even Democrats around the state, he said, but nobody seemed to care until the last few months, and by then it was too late. He thinks what happened to him could easily happen elsewhere.

He’s right, if we let it. Shasta’s recallers are emboldened. I stopped by a barbershop in Cottonwood, a rural town outside Redding, owned by militia leader Woody Clendenen. I asked him what this success meant, and what was next.

Standing near a Confederate flag hanging in the window, with a half-dozen flint-eyed supporters waiting their turn in his antique chair, he told me the militia assembled a list of local politicians that includes the county elections official and the district attorney. He said his group plans on “cleaning house.” He thinks the blueprint they’ve created has proved itself and could work anywhere. So do I.

It might be the only thing we agree on.

Tensions are rising in Shasta County, where a far-right group wants to recall supervisors, has threatened foes and bragged about ties to law enforcement.

We’re going to see more elections across California like Shasta’s, whether for school boards, sheriffs, city councils or supervisors.

Does what happens in Redding matter in San Francisco or Los Angeles? It does. Imagine an alt-right elections official refusing to count mail-in ballots for a state or federal race, citing the conspiracy theory that they aren’t legal. Or a sheriff deciding he’s got the constitutional power to make whatever laws he or she wants. Where does it end?

We need to help elected officials like Moty, regardless of party. I probably wouldn’t vote for Moty if there was someone running to his left, but he’s a public servant with integrity, the “cream of the crop in Redding,” as Chamberlain puts it. We need good people of all opinions in politics, not whoever remains when militias and the alt-right have run off everyone they don’t like.

Moty said he’s done with politics, looking a little shell-shocked, especially for an ex-cop. But he’s not going quietly, because he’s mad, and worried. And the rest of us should be, too.

“If they can take someone with my experience and education and reputation and twist it all around backwards,” he said, “then they can do this to anybody.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.