Trucks stream down Drumm Avenue in Wilmington. Industrial truck traffic has increased heavily on Drumm Avenue since 2019, when the previous truck route was closed. (Carolyn Cole/Los Angeles Times)

The trucks began appearing in the spring of 2019, and at first the residents of Drumm Avenue accepted the occasional rumble and whoosh of big rigs breezing past their homes.

But nearly a year later, not long into the pandemic, a daily convoy of 18-wheelers showed up, turning the once-quiet Wilmington street, a little less than a half-mile long, into a loud and dusty truck route from dawn to well-past dusk that has continued for nearly two years.

Diesel fumes hang in the air. Dirt cakes cars and windowsills. Outdoor conversations are strained, and residents wonder what happened.

They know the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach have been in crisis: ships waiting at anchor, terminals struggling to keep up with the flow of goods. Snags in the global supply chain have always brought additional trucks, containers and traffic into their community. Such is life next to the largest port complex in the country.

What they don’t know, however, is the extent to which a series of decisions, made independently and over time by federal and state agencies, city departments and private businesses, is responsible for transforming their once-quiet neighborhood.

A transportation grant was denied, and a road fell into ruin. A truck route was closed, and a driveway was built. By themselves, they might have had little effect.

But taken together, the consequences have upended life on Drumm Avenue for residents, whose unhappiness is compounded by the fact that they were not warned, consulted or advised. Disregard, they say, is typical of the city of Los Angeles and the ports whose officials have long overlooked their community.

Hemmed in by oil refineries and heavy industry, Wilmington has long struggled against a legacy of redlining, antiquated zoning ordinances, aging infrastructure and most recently, the ever-expanding ports.

But more than just a local problem, the crisis on Drumm Avenue raises questions critical to matters of environmental justice, especially in communities of color. What value does a low-income neighborhood have, and what price is acceptable to maintain peace, quiet and security?

Today the residents of Drumm Avenue keep windows and doors shut, deal with aggravated allergies and try to cope with the stress, health concerns and frustration. They have held demonstrations, shutting down their street and blocking traffic with the hope of catching the city’s attention. They feel they have no other choice.

One recent morning, Imelda Ulloa tried to hide her tears as the trucks streamed by. Close to noon, the traffic was light. The worst stop-and-go backup occurs during commuting hours, but even now the passing of an occasional truck presented problems.

With the road clear — from a container storage depot at the end of Drumm Avenue to Pacific Coast Highway less than two blocks away — clouds of dust rose in the wake of each speeding vehicle, and many drivers blew through the street’s only stop sign.

“Imagine if your family lived here, your parents or your children. Would you want this?” she said, wiping her eyes with her sweatshirt. “I’m tired of this, and I can’t do anything about it.”

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Ulloa and her husband, Jose, have lived on Drumm Avenue for 24 years. The couple recently remodeled their modest home’s backyard with a sunshade, new furniture, potted plants. Ceramic angels and wind chimes decorate the front porch.

Their neighbors, Cesar and Priscilla Vigil, moved to Drumm Avenue five years ago. Wilmington offered the young couple a chance to buy a bigger house than what they could find in west Long Beach, where they used to live.

“If I knew this is what I’d be dealing with,” Cesar said, “I would have never bought this home.”

The Vigils, Ulloas and other residents of the neighborhood question Los Angeles’ commitment to them.

“It feels like we’ve been forgotten,” said Jose Ulloa, who was recently diagnosed with asthma. “The city is getting a lot of money from the port, but not investing any money in fixing the streets or any of our problems.”

*

Like many low-income communities in L.A. County, Wilmington has been a convenient location for the region’s less convenient needs. East Los Angeles got cemeteries. Vernon got a battery recycling plant. Southeast Los Angeles got rendering plants, and Wilmington has the port, whose presence is everywhere.

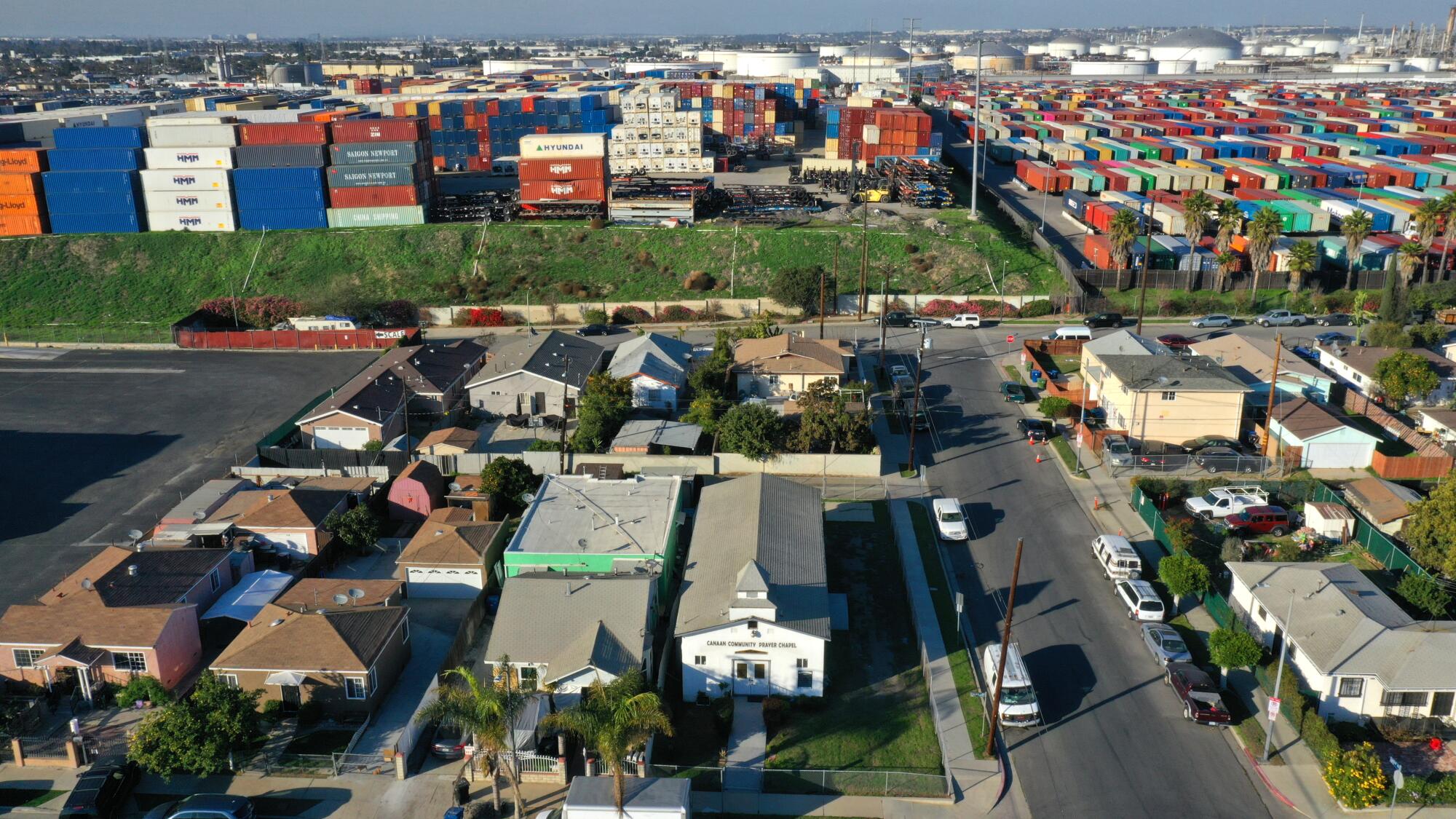

On Sandison Street, a few blocks from Drumm Avenue, homes look upon a towering edifice of the multicolored shipping containers perched on a small hill. Next door, where Anderson Hay & Grain packages fodder for export, come warning alarms of trucks in reverse. The loud wheeze of air brakes proceeds a concussive thud.

Near Drumm Avenue, big rigs hauling 40-foot-long shipping containers cut through residential streets in violation of the posted weight restrictions. Their trailers jump curbs, pounding the earth where signs warn of underground petroleum pipelines.

“How do they think this is OK for us?” said Valerie Contreras, a member of the Wilmington Neighborhood Council. “We’ve been complaining for years. Our neighborhoods are getting whittled away, so we’re left with an industrial city that Los Angeles and the ports have created.”

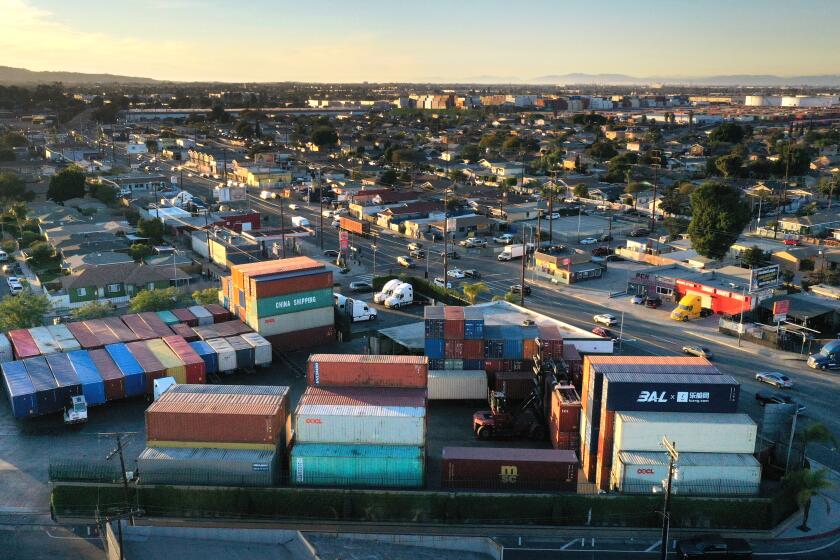

Shipping containers from L.A.’s port are piling up in storage yards across Wilmington. Older facilities are exempt from zoning limits.

One hundred years ago, Wilmington was looking at a brighter future.

Valued for its waterfront, it was annexed in 1909 by Los Angeles, whose deep pockets promised new schools, police, fire services and port improvements.

William Wrigley and Henry Ford invested by building fancy homes and a manufacturing plant. But the Depression threw a shadow on everything, and then oil was discovered.

Wildcatting fever left the region pockmarked with wells, and in 1939, when the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corp. published its assessment of Southern California, Wilmington was colored red on the map, given a D grade and rated “hazardous.”

Describing “a flush oil field embracing the town,” the lending agency declared that “future residential desirability is nonexistent” and an “infiltration of subversive elements is rapidly increasing,” citing Japanese and Mexican nationalities.

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The result, said Eric Avila, an urban historian at UCLA, was “a blueprint for underdevelopment.”

“Redlining made those areas vulnerable to the placement of unwanted infrastructure,” he said, leaving “a legacy of environmental injustice and environmental racism that residents of Wilmington — mostly Mexican and Mexican-American — have had to deal with.”

*

For decades, Drumm Avenue was like many other streets in working-class neighborhoods of Los Angeles. The homes, built between the 1920s and 1950s, slowly filled in around one another, and because they fronted the Pacific Electric Railway — Los Angeles’ old Red Car — nothing was built on the other side of the street.

As far as its residents remember, that’s always been a stretch of dirt and a cinderblock wall topped by concertina wire, cordoning off a 17-acre cold storage facility. When graffiti and trash started accumulating along this no-man’s land, the residents planted bougainvillea.

That was almost 10 years ago, and about that time, you might have found the Campollo brothers, Jose and Jefrey, taking over the street to play football. They kept a basketball hoop in the yard, and a game of horse often meant taking shots from off the sidewalk.

Jose worked on his 280Z, parked at the curb, and would see at most four trucks pass by in the course of a day, safe enough for neighborhood kids to skateboard, play tag, run around.

It didn’t take long for the idyll to change, though.

Where Drumm Avenue ends, there is a small hill owned by Chandler’s Sand and Gravel Co., which leases the property to ITS ConGlobal, an Illinois-based company that maintains and stores shipping containers.

Its Wilmington facility is the largest depot in the area and, along with a few neighboring sites run by other storage companies, is a primary source for the truck traffic on Drumm Avenue.

With two locations, a total of 70 acres, ITS ConGlobal has room for 23,000 containers, making it a landlocked version of the world’s biggest container ship. Here trucks drop off and pick up containers that come from the ports or inland distribution centers, and business is booming.

The depot is open from 8:30 a.m. to 3:30 a.m. The long hours are meant to help ease congestion and pollution at the port, said company spokesperson Wendy Hannon.

Trucks, she said, “can wait at the port for nearly three hours either to pick up a container or drop one off. They do the same at our facility and are able to get in and out in under an hour.”

Hannon cites new technology being used to expedite arrivals and departures at the depot and understands how traffic has affected Wilmington residents.

“Everyone across the supply chain is looking for solutions to ease congestion at the ports, intermodal terminals and distribution centers, while keeping pace with supply and demand imbalances,” she said in an email. “ITS ConGlobal is doing its part. Many of our employees live in Wilmington, and being a good neighbor positively impacts them, and from a business perspective, it’s just the right thing to do.”

Yet as efficient as the facility might be in managing the comings and goings of its containers, the site itself has limitations that it shares with some of the other depots.

The property is not paved, which means a water truck has to spray down the dirt to minimize dust. But the water creates mud, and the trucks’ tires pick up the mud. Some is dislodged on a rumble strip at the exit, but some comes loose on Drumm Avenue, where it dries, gets caught in the wind and ends up coating cars and windowsills.

Also, the property’s entrance is on Lomita Boulevard, and of all the roads and highways serving the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, this stretch of Lomita Boulevard is perhaps the worst.

Last year, up to 3,700 vehicles a day — nearly 2,700 of them trucks — used the road, which is “failing,” according to a civil engineer who studied the route. He described its fractured and spalled asphalt as “alligator cracking” because it resembles the reptile’s scaly skin.

And not all the vehicles on the road are cars or trucks, either. BNSF Railway runs trains over Lomita Boulevard at three crossings, compounding the congestion.

Sandwiched between the container storage yards and an oil refinery, Lomita Boulevard is considered by transportation experts as the best alternative to Drumm Avenue.

But because it forms the boundary between the cities of Los Angeles and Carson, Lomita Boulevard is a stepchild that neither municipality is willing to take full responsibility for.

Seven years ago, they tried working together. They applied for a grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation, asking for $53 million to help cover the cost of improvements — gutters, curbs, lighting, upgraded railroad crossings — but their application was denied: too much money for the benefit of too few.

At that point, the primary users of Lomita Boulevard — Chandler’s and BNSF Railway — began to act on their own.

For BNSF, the situation had grown urgent. On March 28, 2016, one of its locomotives collided with a truck and trailer that had stopped at a crossing and then tried to race across. Four months later, a freight train with 11 cars struck another big rig that didn’t stop at the same crossing at all.

Speeds were low and no injuries were reported, but BNSF officials felt it was just a matter of time and asked the California Public Utilities Commission, which oversees railroad crossings in the state, to intervene.

After a two-year study, the commission decided that the only solution was to reduce traffic on Lomita Boulevard. So they moved to turn the road into a cul-de-sac by preventing trucks from crossing a series of train tracks at Alameda Street.

The owners of the railroad crossing — the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach and the Union Pacific Railroad — had no objection. In announcing the closure in 2019, an executive with the Port of Los Angeles wrote, “It is hoped that any through traffic on Lomita shifts to PCH or Sepulveda.”

But getting to Sepulveda Boulevard can add up to a half hour for trucks going back and forth to the port.

Getting to Pacific Coast Highway was quicker. Trucks could take an old utility road and surface street to reach Drumm Avenue, or if they were coming from the ITS ConGlobal storage yard, they followed a driveway, permitted by the city and built in 2016, that fed straight into Drumm Avenue.

As more trucks started taking these routes, city traffic managers had no reason to object. Drumm Avenue was the best candidate for the traffic, better than other streets with homes on either side.

*

Seven years after the request for federal funds to improve Lomita Boulevard was denied, Wilmington may be getting a second chance.

The Southern California Assn. of Governments is about to release a 478-page, $240,000 study for improving the flow of traffic through the city. The association, which helps develop regional transportation plans across the Southland, consulted with the cities of Los Angeles and Carson, as well as the ports, rail lines, businesses and local residents.

Nine solutions are offered. One costing about $40,000 would widen Drumm Avenue by eight feet opposite the homes. Residents who have heard of this plan oppose it because it does nothing to stop the trucks.

A more ambitious proposal is to build a road that would bypass Drumm Avenue entirely. Without factoring right-of-way acquisitions, that would cost about $850,000.

The residents of Drumm Avenue, however, want Lomita Boulevard reopened to Alameda Street. That could be done immediately and without cost.

But the study does not recommend this because it would increase congestion on Alameda Street and put trains and trucks at risk for collisions, and building a bridge over the tracks has a $350-million price tag.

As for Lomita Boulevard, the report suggests fixing the pavement, re-striping lanes and adding new signage at the railroad crossings.

But before anything can be done, funding has to be secured, which raises two important questions: Where will the money come from? And how much are city, state or federal agencies willing to spend to make life on Drumm Avenue tolerable?

Eliza Jane Whitman, director of public works for Carson, said there is a limit to what her city is able to spend, and since most of the traffic is coming and going to the ports, she wonders why Carson, Los Angeles, the state of California and the ports don’t form a partnership to spread out the costs.

“This is part of the supply chain,” she said. “Why should our community bear the brunt of the costs for the nation’s supply chain? This is something everyone in the United States should be contributing to.”

Meanwhile, Councilman Joe Buscaino, who represents Wilmington and has pressed for a long-term solution, is exploring the possibility of providing residents with air filters and double-paned windows.

*

Wilmington always seemed to live in the shadow of something bigger, as one historian has written, and on a recent Thursday afternoon on Drumm Avenue, residents stepped out of that shadow.

For two days, Imelda Ulloa and her sons went door to door passing out fliers. “I am inviting everyone around the neighborhood of Wilmington that is tired of breathing all this pollution due to all these diesel trucks passing by 24/7 causing all this ruckus … to start a protest.”

Trucks from L.A.’s port kick up dust as drive down Drumm Avenue at E. Q Street. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

A little before 3 p.m., parents, teenagers, young children, retirees and those just home from work began gathering. Everyone had the same story: cars mired in dirt, homes shaking, no playing outdoors.

Soon the sidewalk was crowded. Imelda’s husband, Jose, was at work, but her oldest son, Omar, 30, handed out the red and black lettered signs that he had spray painted the night before.

“We are tired!” one read.

“Aqui Viven Familias.” (Families live here.)

When demonstrators stepped into the street, chanting “No more trucks” and “Sí, se puede,” Drumm Avenue suddenly grew quiet and peaceful but for the sound of their voices.

The Los Angeles Police Department arrived. A politician passed out business cards, and soon the lineup of trucks extended nearly a half mile from Pacific Coast Highway to the driveway at Chandler’s.

Standing 5-foot-2, Imelda took a stand in front of one truck with a bright green cab. Its chrome grill towered above her. Holding her 5-year-old grandson who had fallen asleep, she held her ground.

“Maybe people will pay attention to us,” she said.

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.