I covered the first $3-billion budget in 1963. Now Newsom could crack $300 billion

- Share via

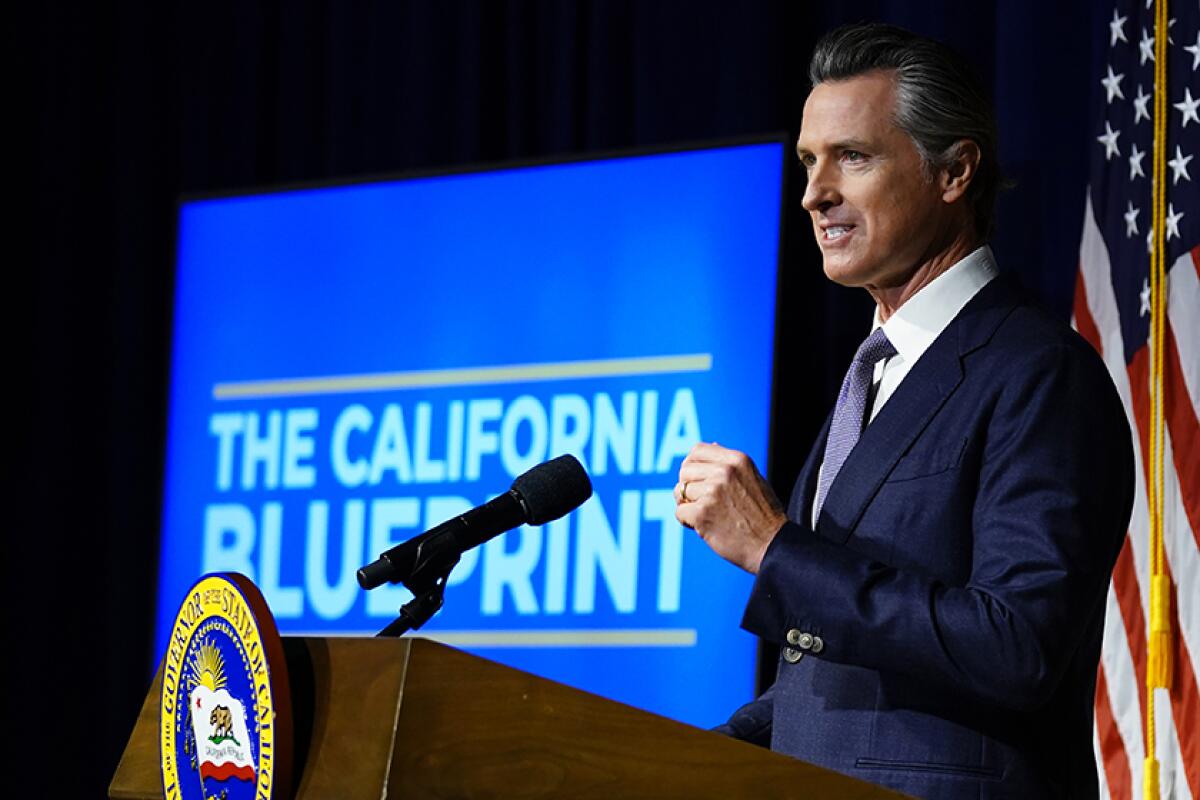

SACRAMENTO — The two most striking things about Gov. Gavin Newsom’s revised state budget proposal are the immense size and mad money.

He’s seeking the first state budget to crack $300 billion — $300.6 billion to be exact. Billion with a “B.”

It’s striking to me, at least, because I covered passage of the first $3-billion budget in 1963. That’s right: 100 times smaller than what Newsom wants.

The mad money this year is the never-dreamed-of tax surplus of $97.5 billion projected by July 2023. Yes, that’s nearly $100 billion over what the state needs to fund what it planned.

It begs the question: Why not just return the excess money to taxpayers?

Part of the answer: “Only” $49 billion is discretionary money. The lion’s share of the rest legally must go to schools — $37 billion.

Newsom and lawmakers could send most of the discretionary surplus back to the people who coughed it up to Sacramento.

But legislative leaders don’t believe the upper-middle class and wealthy — the top 10% of earners — who supplied 81% of the income taxes to be “rebated” deserve to get any of their money back. They say the dollars should be sent to the 90% who kicked in just 19% because these people need it.

Only don’t call it a “rebate.” It’s government aid.

Newsom did propose mailing $400 to every car owner to provide gas price relief. But he’s planning to exclude drivers of “expensive” cars — the definition to be negotiated with legislators. However, they don’t want to return any money based on car ownership.

Newsom thinks $11 billion should go to vehicle owners. It’s part of an $18-billion “broad-based relief” package that includes rental assistance, utility payments, medical insurance subsidies and child-care help for low-income families.

The governor also proposes to sock away a few billion in savings and repay some debt. And he’s adding more to infrastructure projects, but not nearly enough given the easy pickings of windfall money.

Back to 1963 and the first $3-billion budget signed by Democratic Gov. Pat Brown, father of future Gov. Jerry Brown.

Fifty-nine years ago, one dollar was equivalent to the purchasing power of $9.45 today. So, the equivalent of that $3.2-billion budget would be roughly $31 billion now — about one-tenth of what Newsom is proposing.

OK, but California’s population was a comfortable 17.5 million then, 44% of what it is today. So, there are lots more people for state government to serve — but not 100 times more.

The plan would devote billions to an inflation relief package, drought and wildfire conditions, healthcare plan subsidies and higher school funding.

The fact is, Sacramento has taken on many more costly tasks.

In 1963, the governor and Legislature greatly expanded government assistance for low-income mothers and that grew into today’s CalWORKs.

Federal Medicaid was enacted in 1965 and that became Medi-Cal, which provides healthcare for low-income Californians. Roughly one-third of the population is covered. And Newsom intends to extend coverage to the last group of poor people not currently eligible: immigrants between the ages of 26 and 49 living here illegally.

California is “on the path to being the first state to have universal healthcare,” Newsom bragged in announcing his budget revision Friday.

He has budgeted $53 billion in state money for Medi-Cal.

Compared to 1963, state government also is much more responsible for financing schools and local government because Proposition 13 shrank property tax revenue.

Proposition 13 was overwhelmingly approved by voters in 1978, when home property tax assessments were rising through the roof. Meanwhile, Gov. Jerry Brown and the Democratic-controlled Legislature dithered. They failed to agree on property tax relief while holding onto a roughly $5-billion surplus that state Treasurer Jesse Unruh famously called “obscene.” The state budget then was $18.7 billion.

If alive, Unruh certainly would use stronger language to describe the current surplus.

One more nostalgic note: In 1963, state government spent $5.81 per $100 of personal income. Today, it’s spending nearly double that: $10.85.

Spend is what this generation of Sacramento Democrats does best — usually without monitoring whether the dollars are wasted. That’s the main reason the surplus isn’t returned to taxpayers. If it were, politicians couldn’t spend it.

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s proposed budget includes $65 million for his CARE Court proposal, but major funding questions remain.

In 1963, the Legislature was still “part-time.” Then-Assembly Speaker Unruh and Gov. Brown hated each other. Republicans were strong enough to create havoc. But they all coalesced to compromise on substantive public policy, such as the very contentious fair housing bill that outlawed racial discrimination in sales and rentals.

In this era, the governor and legislative leaders are in sync, but don’t challenge each other and get little substantive done beyond writing big checks. And weak Republicans are ignored.

In his budget news conference, Newsom touched on two “third rail” issues — presumed to be politically untouchable — that he’d like to reform. But he either doesn’t know how, thinks it’s too risky or lacks the gumption. Maybe all three.

One is the archaic California Environmental Quality Act, often used to block housing projects with frivolous lawsuits.

“I criticize not CEQA, but the abuse of CEQA,” he said. “I’ve been on the receiving end of CEQA abuse in my private life.”

The other issue is tax reform. California’s outdated system is unreliable and unsteady in times of boom and bust because it leans too heavily on wealthy people and their capital gains. Income tax rates should be lowered and the sales tax broadened to services.

“We should reform the tax system because of the volatility,” Newsom said. “A lot of states tax services, and we don’t.”

The first $100-billion budget was passed in 2002. The next year, Democratic Gov. Gray Davis was recalled by voters.

At this rate, some young Capitol reporter covering Newsom’s $300-billion budget will be around to opine about the first $1-trillion spending plan. I suggest using Unruh’s adjective: “obscene.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.