Acrimony, threats, absent doctors: L.A. County and USC clash over hospital management

- Share via

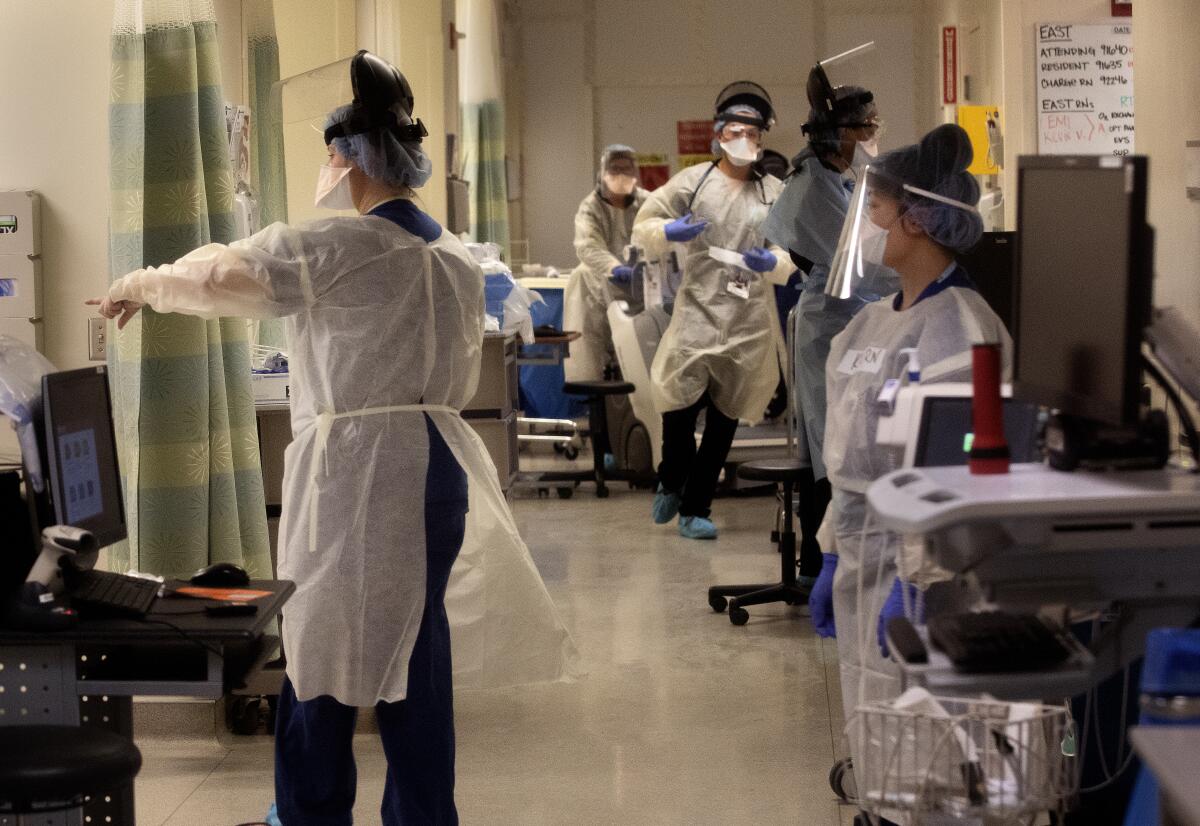

For years, a contentious dispute between Los Angeles County’s healthcare leaders and the University of Southern California has seethed behind closed doors, injecting tension and acrimony in the operations at one of the nation’s busiest public hospitals that climaxed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

As early as 2019, officials at L.A. County-USC Medical Center in Boyle Heights began accusing USC of failing to live up to its contract obligations, where the county pays up to $170 million each year in return for USC’s faculty doctors and nearly 1,000 medical residents treating some of the region’s poorest patients.

The county has contended that USC repeatedly fell short of providing enough doctors under the contract while also “double-booking” its internists, cardiologists, and others — claiming they were scheduled to simultaneously treat patients at both the public hospital and the university’s privately owned Keck Hospital across the street.

Last spring, the second-in-command of the county’s health services agency, Dr. Hal Yee, informed USC that it had breached its contract. In scathing correspondence, Yee documented two years of meetings and reviews that he said indicated “underperformance” and “a broad lack of accountability and responsibility on the part of the university.”

The complaints from the county have partly spurred change at USC, which since 2020 has installed new leaders atop the medical school and healthcare enterprise, replaced some physicians that directly interface with the hospital, and retained consultants to ensure compliance with the county.

But the university also fired back.

While USC has acknowledged some “areas of challenge,” they’ve rejected the idea that a true breach of contract ever occurred. USC also lodged a host of complaints about the County, including that it responded to physicians’ concerns “with hostility and demands for retributive action,” resorted to threats to oust a USC administrator, ignored the university’s aid to the county during the pandemic, and repeatedly highlighted past problems in a way that’s “divorced from the reality on the ground.”

“The continual rehashing of issues that have been resolved and attempts to escalate routine staffing issues into contractual breaches makes us question whether County’s actions are simply a pretext to alter the [contract] to County’s advantage,” wrote Dr. Steven Shapiro, USC’s top health executive, in a Nov. 8 letter.

This week, both County and USC leaders stated that the once-fractious relationship between leaders at the two institutions had dramatically improved in recent months.

“The people at the County have accepted us and given us a chance to develop a relationship,” said Shapiro, who was appointed by USC from the University of Pittsburgh last year, the same month the County declared a breach.

Shapiro denied that USC ever double-scheduled physicians and said some of the issues derived from doctors working part of the day at one hospital before being scheduled at another later in the day, a practice that is now prohibited.

The County’s Department of Health Services said in an unsigned statement that it would not make anyone available for an interview. Although the “material breach” is not fully resolved, the statement said USC and the county were working “in good faith” to address issues.

“We emphasize that the majority of the contract was abided by, and we value the quality of services provided by, and the partnership with, USC,” the statement said.

Supervisor Hilda Solis, whose district includes the 600-bed hospital, said in a statement: “I have been assured that progress has been made in resolving the serious issues identified.”

The impact on patients is less clear. While county officials repeatedly claimed there were “absences and late arrivals” by physicians, and that staffing “gaps” affected access to care, the county acknowledged in a statement that it was “not aware of any adverse patient incidents.”

Shapiro maintained that the dispute centered on the bureaucratic process around documenting time, which did not undermine care: “Our doctors are taking care of patients. They aren’t looking at the clock,” he said.

L.A. County and USC have partnered in running a hospital for more than 135 years, but the recent dispute traces back to a contract that was renegotiated in 2018 and 2019, amid tumult at the university following a series of scandals centered in its healthcare operations.

That contract, which took effect July 1, 2019 — days before Carol Folt formally took over as president — changed how the university was to be compensated, from the number of full-time employees to the number of hours worked.

Shapiro and other USC officials said the new hourly system posed significant administrative burdens. “Doctors aren’t used to being paid by the hour,” he added. But in the wake of the County’s issues, he said, USC began requiring doctors to check in and out.

“I must tell you, this isn’t very popular with doctors,” Shapiro said.

In a timeline summarized in a May 2021 formal notice of a contract breach, the County said that in the months after the new agreement kicked in, Dr. Brad Spellberg, the chief medical officer at County-USC, began alerting the university of repeatedly falling short in anesthesiology by 200 hours each week, and that the infectious disease division was likewise not meeting contract terms. By the winter of 2020, the county said it was reducing payments first by $4.7 million, then $6.2 million, because of failure to provide the physician service it had purchased.

According to county correspondence, Spellberg also began hearing from a USC-employed physician who was “not comfortable” with the double-booking practices and would not sign documents attesting to work supposedly done by USC doctors. Later, an anonymous faculty member alerted Spellberg to double-booking among cardiologists.

The county performed an audit of the cardiovascular division and claimed that it showed hundreds of instances of double-booking or no physician coverage for clinics from September 2019 to September 2020.

At a series of meetings in 2019 and 2020, Spellberg and others raised issues to USC administrators, including Dr. Glenn Ault, Dr. Hugo Rosen, and then-Dean Laura Mosqueda. Rosen died in December, and Mosqueda abruptly resigned in the summer of 2020.

In a May 2021 letter, the County claimed that USC’s “lack of responsiveness and accountability have caused unnecessary delays in resolving these issues,” prompting it to declare a breach of contract that required a plan for correction within 90 days.

USC’s interim medical school dean, Dr. Narsing Rao, countered the next month in a 14-page letter that pointed out the problems raised by the county were confined to just two of the 17 departments at its medical school, and that these were “operational issues,” not breaches of contract.

Rao said the double-booking allegations were under investigation, but said the data used by the county were “inherently flawed” because the software was a scheduling system, not a time-tracking platform. He also said many of the issues were borne out of routine issues in healthcare, or derived from “communication, cooperation and coordination issues” between USC and the county.

“The highest levels of the university leadership have worked on the County relationship over the last nine months,” Rao wrote, summarizing key changes. Among them: removing the physician who serves as USC’s formal representative to the county after the county demanded it by “even using threats.”

Yee, a top county health executive, replied on Sept. 22 by repeating that USC’s “underperformance constitutes a material breach.” He decried “inexcusable service gaps,” and a “blatant unwillingness” to comply with the agreed-upon contract.

“These issues necessitate changes to the University’s internal management process,” Yee wrote. “Overall, the University’s response reflects a reactive approach to the County’s concerns.”

Shapiro responded about six weeks later by pointing out what he called misstatements and highlighting that an hours-base contract did not work well in a patient care environment.

“The letter has led to a growing sense at the University that, notwithstanding the implementation of significant improvements at great cost to the University and the replacement of many physicians at your request, it never seems to be enough,” Shapiro wrote.

Shapiro offered to abandon the “unpleasant letter-writing” and sit down for a meeting with the county. In an email the next day, Yee agreed and offered “to schedule the first meeting as soon as possible.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.