A former bracero farmworker breaks his silence, recalling abuse and exploitation

- Share via

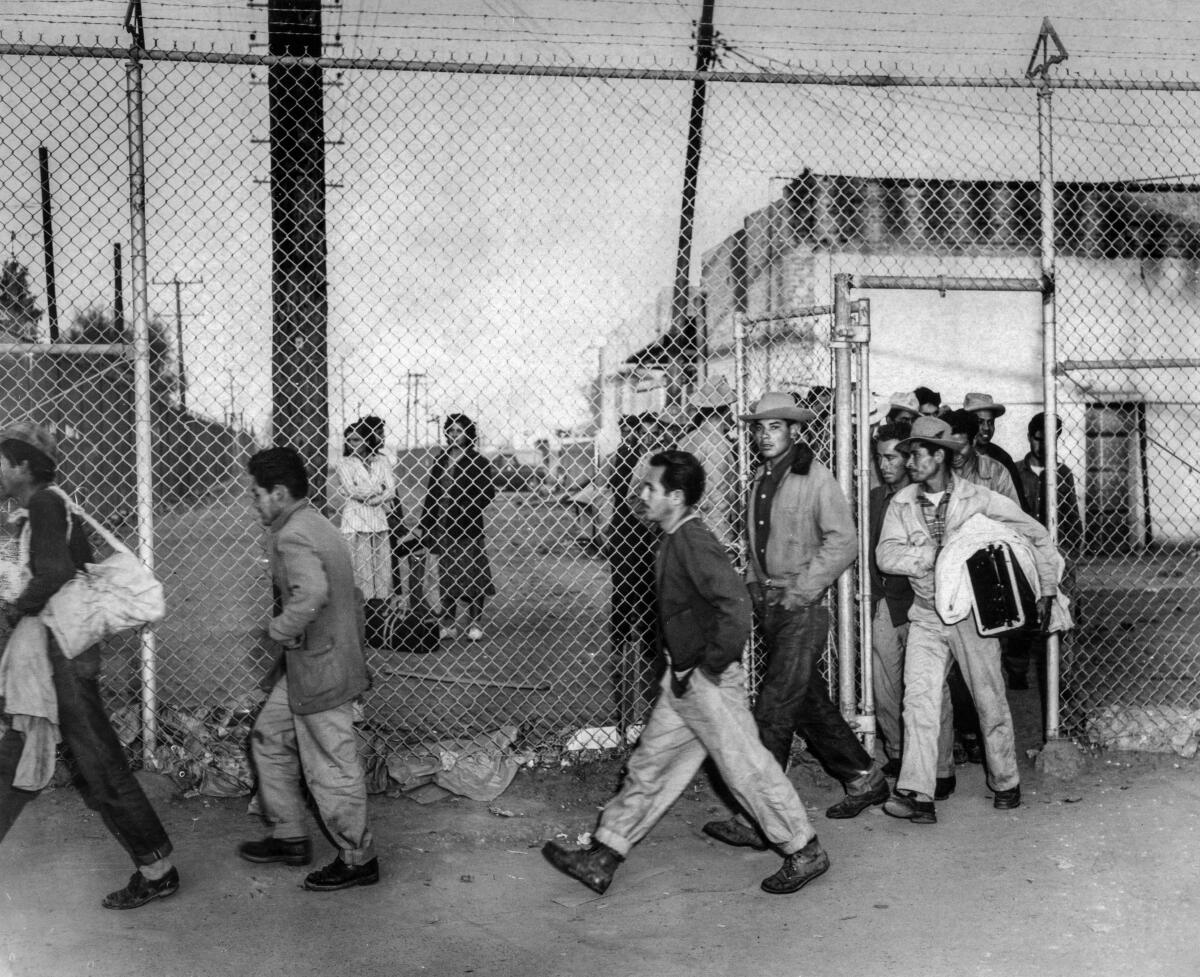

From 1942 to 1964, the bracero program allowed Mexicans to cross the border to work on U.S. farms and railroads. They were received with DDT baths and humiliating inspections. Fausto Ríos arrived in the country as part of this program when he was 17, and this is the first time he’s shared the story with his family.

- Share via

Crouching for up to 10 hours between the furrows of a Nebraska field, Fausto Ríos, 17, could trim and separate 70 beets in a single minute with a small hoe. But he paid a steep price.

Under the scorching heat, sweat would bathe his entire body and blind him within minutes. When his legs began to weaken and the pain in his lower back felt as if he were being continuously stabbed, the Mexican immigrant had two tricks to motivate himself and avoid a scolding from his bosses: He had to stay upright as he “walked” on his knees, all the while thinking about getting paid at the end of the month.

Despite the extreme hardships, the job was a godsend for him and millions of other young Mexican men, Ríos says. For immigrant laborers with little or no formal education and a lack of employment opportunities in their native land, laboring in the fields of el norte offered a way out of utter deprivation.

“Being tied to the ground for hours is not easy, but then I was a young man with many dreams,” Ríos murmurs as he stares out the living-room window of his home in Colton, an hour east of downtown Los Angeles. “But some dreams turn into nightmares that must become part of history so that we don’t repeat them.

“That’s why today I am breaking my silence.”

For decades, the 82-year-old has kept his experiences as a migrant farmworker in the bracero program a secret from all but close family members. The father of four felt ashamed to tell his children — Fausto, Hector Hugo, Dora Luz and Jesús Manuel — about the indignities and abuses by unscrupulous bosses that he endured without ever filing a complaint. His children knew only that their father had been a farmworker.

Now a widower, with a damaged back, arthritic knees and a treadmill as his constant companion, he wants to play whatever role he can in exposing, and ending, the long history of racism, wage theft and mistreatment that many farmworkers experienced between the early 1940s and the mid-’60s.

He believes that sharing his story will give voice to all those immigrants who still are tethered to a system that, he says, exploits them and repays their sufferings with indifference.

“In my last days, I want to share an ‘immigrant worker history class’ in the United States to make our future generations aware that no human being deserves to be treated like a disposable machine.”

In August 1942, in response to the farm labor shortage during World War II, the United States and Mexico signed a binational agreement to initiate the Mexican Farm Labor Program, better known as the bracero program, for Mexican workers to work in the U.S. temporarily on farms and railroads. The program was named for men who work with their arms, or brazos.

Ríos was excited about the prospect of escaping an impoverished home and an abusive stepfather who put him to work at age 7 selling ice cream and other frozen treats and sometimes planting beans or corn. He had to quit school after the fifth grade.

In 1957, the 17-year-old Chihuahua native bid his mother goodbye with a hug and joined the ranks of some 4.6 million Mexican workers, most of them from rural areas, who were hired through the bracero program that would last until 1964.

The U.S. government guaranteed a 30-cents-per-hour minimum wage, plus free transportation, food and housing. In the northern Mexican state of Durango, where he’d grown up after his mother remarried, Ríos knew young people who’d worked in the United States and returned to their hometown with fine clothes, radios, cars.

He joined a flow of applicants for the bracero program who arrived at reception centers set up in various parts of Mexico. Many had to wait weeks to register, surviving on candy and peanuts, and sleeping on cardboard and newspapers.

Ríos was among the hopeful young men who’d been duped by coyotes, the Mexican smugglers who pocketed exorbitant fees in exchange for false promises of helping workers to jump the long application lines. “I had to leave home, get away from my stepfather who had branded me stupid and useless all my life, and start a decent life according to me,” Ríos says. “But I ended up losing my dignity.”

The history of the braceros has been explored in numerous books, documentaries and journalism outlets, and much of that content can easily be found on the internet. But historians and farm labor activists emphasize that it’s essential to keep recording and preserving their stories to convince politicians of the continuing need to improve working conditions for farmworkers.

Last summer, Rosa Martha Zárate Macias, 80, a member of the coordinating team of La Alianza de Exbraceros del Norte 1942-1964, an organization that represents braceros in Northern California, published a book dedicated to them and raising alarms about conditions for migrant farm laborers today.

In “Our Grandfathers Were Braceros and We Too,” written by Zárate Macias and Mexican historian Abel Astorga Morales, farmworkers recount being recruited, coming to the United States and, all too often, being mistreated by bosses. Some testify to waiting days, weeks and even months in line to obtain permission to enter the United States, just as Ríos did.

The book also highlights the humiliating medical exams that aspiring braceros had to go through. It was standard policy to force applicants to strip naked in public to be checked for venereal disease and hemorrhoids, and to be “disinfected” by being sprayed with dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, better known as DDT, a pesticide that was banned by the Environmental Protection Agency in 1972 because of its harmful effects.

“They squeezed their arms, their legs. They saw if their hands had calluses. They opened their mouths and then they chose the strongest, youngest and healthiest, just as they did with the Black slaves,” says Zárate Macias, who also helps braceros fight to recover still-unpaid wages by staging rallies and marches.

Ríos remembers it all. “I felt dehumanized, like an animal.”

The book also documents how many braceros lost their savings funds. Ten percent was extracted from their weekly paychecks by the U.S. government and delivered to the Mexican government, which was supposed to be in charge of maintaining the funds in a “savings account” and then distributing them to farmworkers when they returned to Mexico. According to a study by economists at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, the total amount owed to the braceros — 500 million pesos — would today be equivalent to more than 5 billion pesos (approximately $248 million), including interest, covering nearly 4.7 million signed contracts.

In 2001, a class-action lawsuit was filed by several former braceros in a federal court in San Francisco against the governments of the United States and Mexico, three Mexican banks and Wells Fargo Bank, where the money was deposited and then transferred to the National Rural Credit Bank of Mexico. A federal judge dismissed the lawsuit in 2002, citing expired statutes of limitations and sovereign immunity.

It wasn’t until Oct. 8, 2008, that the Mexican government, through an out-of-court settlement, agreed to pay about $3,500 apiece in compensation to approximately 250,000 braceros who could prove with original documents that they worked in the United States between 1942 and 1946. But many workers lacked documents and never received compensation. And the settlements were paid only to former braceros living in the United States.

In 2005, the Mexican government, under President Vicente Fox, agreed to pay 38,000 pesos (roughly $3,400 at that time) to each bracero living in Mexico. But during the subsequent administration of Felipe Calderón, the payments decreased to 4,000 pesos, before Calderón’s successor, Enrique Peña Nieto, shut down the program entirely.

Twelve years ago, with the aid of Zárate Macias, Ríos traveled to Baja California to show proof of his former employment and obtained $3,000 in return for seven years in the fields of Nebraska, Texas and Colorado. He says the amount didn’t include the interest he earned.

When the bracero program ended, many undocumented immigrants decided to stay in the United States and continue working in the fields, and many others continued to come in succeeding years. In 1986, Congress passed and President Reagan signed into law a massive immigration reform bill that raised penalties against employers for hiring undocumented workers, but also granted amnesty to anyone who’d entered the country illegally before 1982.

Gaspar Rivera-Salgado, director of the Center for Mexican Studies at UCLA, says the H-2A visa program, created by the U.S. government for temporary agricultural workers in 1992, takes advantage of workers by tying them to a single employer or recruiter, just as the bracero program did. Employers do not have to pay Social Security or unemployment taxes to more than 200,000 farmworkers, as they are required to do for domestic workers.

When the bracero program ended, “the need and dependence on those workers continued,” Rivera-Salgado says. “And this situation gives rise to all the political debate about what to do with this migration and the abuse that their situation leads to.”

The Biden administration has proposed making the majority of the nation’s 2.4 million farmworkers who lack immigration status immediately eligible for green cards and for changes in the employment verification process and worker rights laws that would benefit migrant laborers.

Ríos no longer can recall all the names of the ranches that employed him. But his memory is clear about employer expectations that he and his compañeros would labor more than 12 hours a day, six days a week.

There was no overtime pay. If they took a break for a quick rest, or to relieve themselves by squatting among the crops because there were no toilets, their pay was docked. Promises of free meals usually turned out to be worthless.

When the beet thinning season ended in Nebraska, Ríos asked to go to Texas to pick cotton. Each worker dragged a sack around his waist that weighed 100 pounds when it was filled.

The life there — brutal hours, harsh conditions, physical torment — was similar to that in Nebraska. Then Ríos moved on to northern Texas, packing cotton, watering crops, feeding geese and cows, and putting up fencing.

On one Texas farm where Ríos worked, about nine braceros lived in a warehouse set up as a bedroom without air conditioning or heating. The workers had to take turns sleeping on the limited number of beds. Their other option was the floor.

Dolores Huerta, the activist who fought for migrant workers’ rights alongside Cesar Chavez and has continued her work for 70 years, is among the most prominent living witnesses to the braceros’ plight.

In 1955, when she was a founding member of the Stockton chapter of the Community Service Organization, Huerta helped injured workers obtain compensation. Although the U.S. government gave contractors $1.75 per bracero to help offset room and board costs, many contractors, Huerta says, kept the money, adding that some employers rented out the braceros with noncertified contractors to perform jobs they had never done before.

“In many cases, the braceros ended up injured, and the contractors returned them to Mexico without reporting the cases and without any benefit,” Huerta says. If the braceros refused to work, some employers threatened to have them arrested. Some braceros went on strike, but in most cases the rebels were quickly rounded up and fired or deported.

The old bracero says his heart wants to go on for many years to come. But burdened with prostate disease, blood clots and early Parkinson’s, Ríos knows that his body could give up at any time.

Even though he believes the duty of the last remaining braceros “is to make noise about almost 100 years of abuse,” he insists that he’s not angry with the country that gave him permanent residence in 1971, enabling him to buy his Colton home eight years later. But he grieves to see a new generation of migrant workers suffering much as he did.

U.S. Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-San Jose) shares Ríos’ view that the troubled migrant worker system must change.

“We completely depend on them to feed the nation. It is really unfair that such an essential group of people have to look over their shoulders and live in fear of deportation,” says Lofgren, who with Rep. Dan Newhouse (R-Wash.) co-sponsored the Farm Workforce Modernization Act of 2021. The bipartisan reform bill would provide undocumented farmworkers and their family members with a path to legal status and citizenship, and would revise the H-2A farm visa program to offer more job protections and also a path to immigration status and citizenship for a limited number of workers. It passed the House of Representatives last year and is supported by the Biden administration but has stalled in the Senate.

After the bracero program expired in 1964, Ríos went back to Durango, where he met his future wife, Simona Amaya. By 1967 they had moved to El Monte, a heavily Mexican enclave east of Los Angeles, where Ríos worked as a marble sink repairman until retiring in 2007.

Two of his children will never get to hear their father’s stories of his earlier trials. His daughter, Dora Luz, died at 44 from laryngeal cancer. Hector Hugo, steeped in depression after the death of his older sister, took his own life at 43.

In January 2020, Ríos lost his wife to complications from diabetes.

Since his retirement, the old bracero has allowed himself to sleep in late. He enjoys keeping up with the news on TV and watching soap operas and sports programs. He feels relief that he no longer must obey the march of the clock marking off another day of hard labor.

“It has taken me time to come to the conclusion that speaking is healing. Even if it hurts, speaking is allowing others to learn from your mistakes,” Ríos said.

“With my testimony I want to sow the seed of moral responsibility, so that the new generations and politicians reap laws that respect the work of immigrants who leave their lives on farms.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.