On a patch of sand near the Oceanside Pier, a student director called “Action” on a recent Friday afternoon, sending actors into motion during the filming of a comedy short named “Pick Up Chicks.”

The plot, involving a guy trying to catch the eye of a young woman, was goofy and paper thin. But the filmmakers were flat out serious as they hustled to get a good shot while the lighting was just right.

This story is for subscribers

We offer subscribers exclusive access to our best journalism.

Thank you for your support.

Hollywood has come to San Diego County by way of a tiny, virtually unknown Catholic school whose 253 students could fit into a large lecture hall — if it had one. Which it does not.

As it nears its 20th anniversary, John Paul the Great Catholic University of Escondido has emerged as a vibrant trade school for the film and TV industries, one that’s sending alumni to entertainment powerhouses, including Netflix, Paramount and Marvel Studios.

Theology is part of the core curriculum. So is philosophy. And everyone gets a very deep grounding in business. But the emphasis is on turning students into everything from actors and directors to screenwriters, camera operators and sound experts.

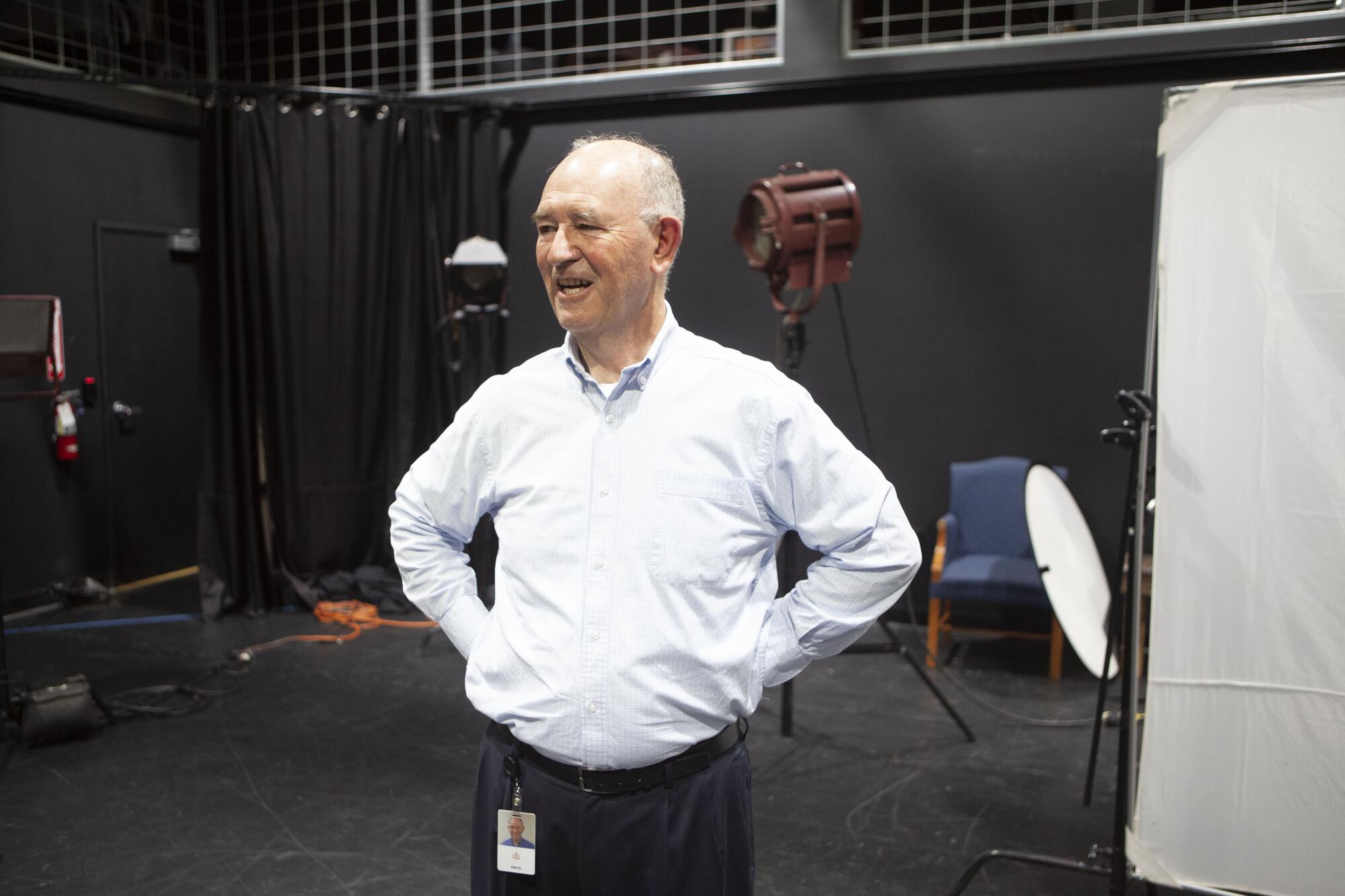

“We’re non-traditional in every way,” says Derry Connolly, the school’s founder. “Students get their hands on the equipment right away. They’re doing shoots all the time. [Sometimes] they film at my house, and I’ve seen them really get into it. You have to be passionate to be good.”

Over the past year, students worked on more than 150 productions, ranging from quick hits like “Chicks” and music videos to documentaries and a new feature-length movie called, “O, Brawling Love!”, which uses Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet” as source material. It was written by Bella Lake, a student, and was directed by alumna Maggie Mahrt, a respected Hollywood filmmaker.

Known as JP Catholic for short, the university plans to produce one major movie a year. And the school will soon have more room to work. It’s about to spend as much as $5 million to renovate a bland brick building in downtown Escondido so that it can house feature film production facilities, a recording studio, an actor’s Black Box studio, a fine arts workshop, and a virtual production lab.

The expansion also will help flesh out the school’s animation, illustration and graphic design programs, and more than double academic and production space.

There are plans to more than double enrollment to 600, as well as to convert part of Escondido’s former Center City High School, which the university owns, into a chapel.

“We’ll be engaging with more students who are looking for a place where they can integrate their faith and passion for storytelling in film and television,” said Nate Scoggins, a Hollywood writer and director who also teaches at JP Catholic.

The school’s practical, get-it-done, high-energy approach reflects Connolly’s personality, education and professional background.

He’s an Irish immigrant who earned a doctorate in applied mechanics at Caltech in 1982 and went on to serve as a senior engineer at an Eastman Kodak imaging facility in San Diego, and as an advisor to IBM.

Connolly, 67, also was an associate dean at UC San Diego, where he helped develop digital media and web technology.

“It was pretty clear in the early 2000s that the internet was going to be huge,” Connolly says in a YouTube video that recalls the school’s rise.

“It was also extremely clear that media was an evil force in our culture. Increasingly, Satan was using media to take souls away from the Lord.”

Connolly’s determination to push back is reflected in the school’s motto: Impact culture for Christ.

While some students go to work in traditional evangelist media, the university has its sights on careers in the mass market.

The school’s faculty say they’re trying to produce skilled storytellers who create content that has broad appeal and explores humanity in clear, candid ways, particularly when it comes to faith and family.

“I’m thinking about films like ‘A Quiet Place,’ which is about a family in a post-apocalyptic setting where you can get destroyed [by aliens] if you make a sound,” said George Simon, who teaches film production at JP Catholic.

“The youngest child gets killed in the opening of the film. Two years later, the mother is pregnant and the family is preparing to bring another child into the world, despite the danger it poses to their survival,” he explained. “It says that life is worth fighting for, worth nurturing. This is not a Christian movie. But the Gospel is present.”

Reaching the masses also is a priority for Connolly, whose take on the matter is a bit harder-edged than Simon’s.

“Christian films sort of feel good but never seem to wrestle with what I would call the horror of sin,” he said. “From a Catholic perspective, we’re much better at dealing with depravity. We don’t sugarcoat it.”

Students are permitted to explore any issue they want, including abortion. But there’s unease about addressing the political wars that have divided the country.

“I was on Twitter looking at [comments about] this horrible shooting in Highland Park,” Connolly said. “They were saying, ‘Can we identify this [shooter] with the left or with the right?’

“I was like, my gosh, there are six people dead. There are 50 people shot, and you’re looking for a political agenda? So we have found with the student body that it is far better to stay away from political things that divide.”

JP Catholic enrolled its first students in 2006, when it was located in an industrial park in San Diego’s Scripps Ranch community. The plan was to start small and grow incrementally, even after the school moved to Escondido in 2013. There was no desire to achieve the sort of size and cache enjoyed by the film programs at UCLA and New York University.

Connolly runs a lean operation. The school does very little advertising, relying instead on word of mouth and social media to generate attention. And JP Catholic mostly hires industry professionals as teachers, rather than creating a traditional, and potentially expensive, tenured faculty.

Tenure “is a disservice to everybody,” said Connolly, whose words are sacrilege in conventional higher education. “We’re a performance-based culture. If we have faculty who perform well, they stay with us forever. If you’re not performing, you go.”

His hires include Scoggins, who enlisted the help of 20 students and alumni last year while he was directing the murder mystery “What Remains” in Texas, and Simon, who recently gave students an inside look at how he was preparing to shoot “Don’t Get Eaten,” a zombie comedy filmed in Michigan.

It can be a challenge for students to keep up with it all. JP Catholic is a year-round school that’s broken into three quarters, each costing $9,000. The goal is to get students through college in three years instead of four.

Virtually all students receive financial aid. The school, which had an $8-million budget last year, also is underwritten by comparatively small private donations. The Roman Catholic Diocese of San Diego has not been one of the school’s financial supporters. But JP Catholic operates with the diocese’s consent.

Students are often left to figure things out for themselves. That’s where Faustina Ortiz found herself recently when she showed up in Oceanside to direct “Pick Up Chicks.” The beach was packed on a balmy afternoon, which meant she had to be careful about how she framed her shots.

“This little project is preparing us for real-world experiences,” Ortiz told the San Diego Union-Tribune between takes. “I’m working with actors, finding out what they need to give their best performance.

“It’s all very helpful, very useful.”

Nearby, classmate Bryson Armstrong stood by, ready to help, and was enjoying the experience.

“I’ve had the opportunity to work on full-length features, independent films, shorts and documentaries,” he said.

“And I’ve only been here nine months.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.