After nearly 200 years, the Tongva community has land in Los Angeles County

When Kimberly Morales Johnson gazes up toward the San Gabriel Mountains, she sees the story of her community, the Tongva, Los Angeles’ first people, written on the granite.

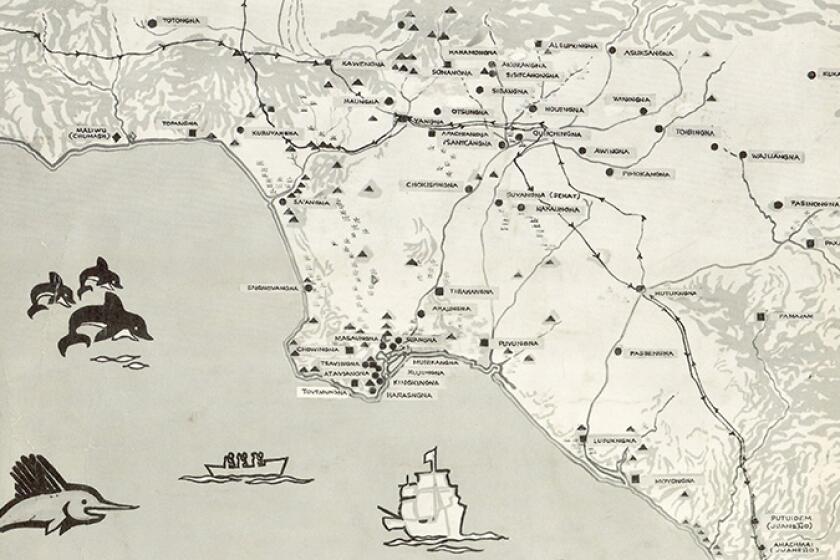

For thousands of years, the Tongva turned to these chaparral foothills and mountains during spring and summer months for food. Its canyons served as trading routes, connecting the flourishing communities of the Los Angeles Basin with Native communities from the Mojave desert.

For the record:

11:15 p.m. Oct. 10, 2022A previous version of this article incorrectly identified Sharon Alexander as Sharon Alexander Dreyfus.

A previous version of this article said the California mission system ended in 1883. The correct year is 1833.

Johnson recounted the history this month from the edge of a property with a Spanish ranch-style house in Altadena built along Eaton Canyon. By the time the house was completed in 1931, after centuries of displacement, enslavement, incarceration and genocide during successive waves of settlers — the Spanish, the Mexicans and then white Americans — the Tongva were largely invisible in their ancestral home of Southern California.

But Sharon Alexander , the owner of the Altadena home and its one-acre property, learned of the community’s desire to obtain ancestral lands. And in a land transfer made public Monday, Alexander agreed to return the parcel to the Tongva people, marking the first time in nearly 200 years, since the California mission system ended in 1833, that they would have land to call their own.

Tongva leaders said they hope the land can provide paths for the community to reconnect with its culture and promote healing from the centuries of trauma.

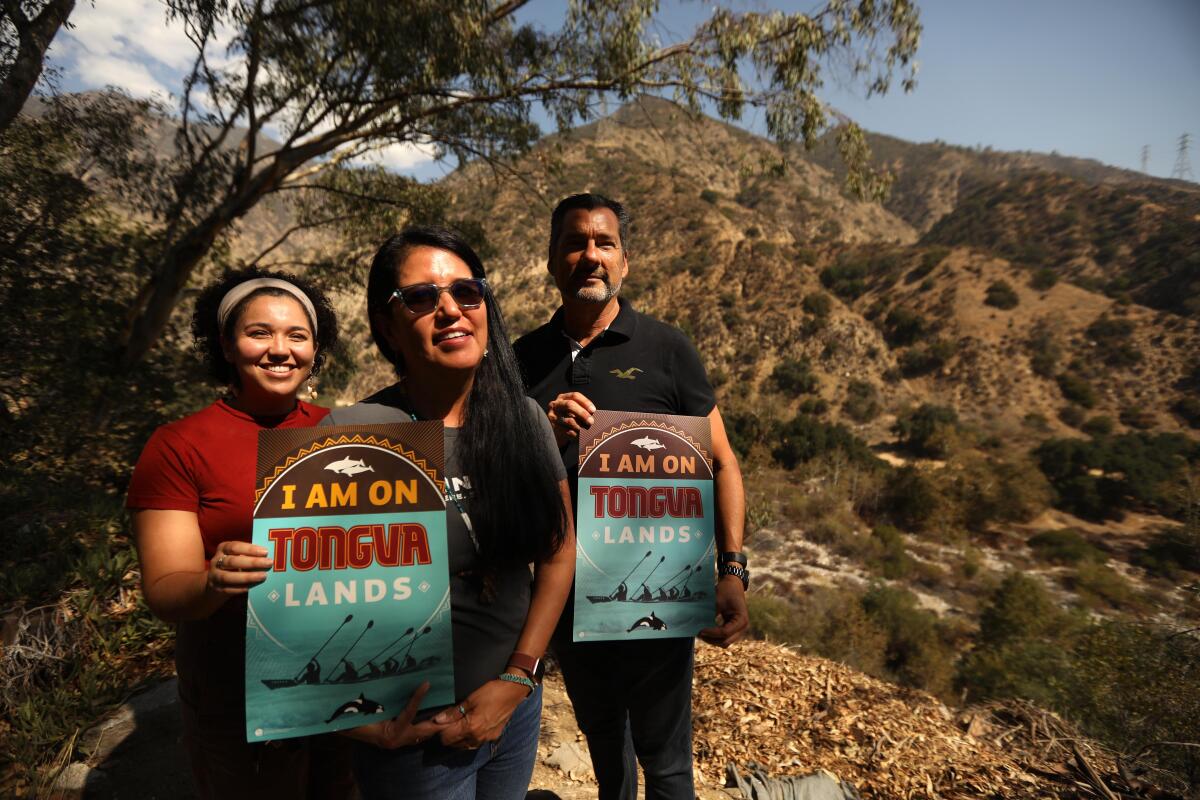

“We’re working towards one common goal, and that is to have a place of safety, security, where we can have ceremonies and where we can exercise our self-determination,” said Johnson, vice president of the Tongva Taraxat Paxaavxa Conservancy, the nonprofit set up by the community to receive the land. “That’s where the healing has begun.”

Located amid Altadena’s suburban sprawl, the donated property is easy to miss. While neighbors preferred gaudy gates and manicured lawns, the Tongva site is tucked within a canopy of oak trees and shrubs.

“It’s a beautiful place,” said Wallace Cleaves, a member of the Gabrieleno/Tongva San Gabriel Band of Mission Indians and president of the conservancy. “Another community member described it as ‘a green cathedral, a church made out of oak leaves.’”

The oak trees, indigenous to California, bear acorns, which are sacred to the Tongva community and a staple in traditional meals.

Without land ownership, carrying out ceremonial practices — such as solstice and equinox rituals, as well as mourning ceremonies for the community’s dead — has been difficult for the Tongva community. Cleaves recalled his father’s mourning ceremony, where more than 100 community members crowded inside their Claremont home.

Even with the permission of local governments or academic institutions to enter its sacred sites, the community faced restrictions on the size of gatherings and on access to the wildland that has the plants necessary for ceremonies.

Tongva and many Native communities see plants, animals and humans as interconnected, equal life forms, said Johnson’s daughter Samantha, who is working to re-indigenize the plant life on the Altadena property.

About 18 oak trees already occupy the property, Samantha said during a visit to the site in October, the start of the usual harvest season for acorns. While she spoke, several acorns bounced atop a Prius and Toyota pickup truck parked on the driveway. Acorns dotted the gravel surface of the property.

Samantha is planning a harvesting day for community members to gather acorns from the trees.

“This is a place where we can grow our plants and say, ‘This is how we take care of it, and how it takes care of us,’” she said. “It will really help with our cultural revival, because our plants are a part of us.”

Reclaiming ancestral land is rare for any Native American nation, tribe or band. Peoples including the Tongva who were tied to California’s old Spanish missions lack federal tribal status, which presents an additional challenge, said Angela Mooney D’Arcy, who heads Sacred Places Institute for Indigenous Peoples, a grass-roots group led by Native people in California.

Mooney D’Arcy traces a history of the U.S. government’s broken promises of ceding reservation lands, of displacement in favor of white settlers, and California’s policy of killing Native Americans in exchange for money at the state’s founding. L.A. County laws targeted and jailed large swaths of Native communities, selling members off for convict labor to tend citrus orchards, clean L.A.’s streets and build the city’s burgeoning neighborhoods.

Many ancestral Indigenous lands have since been developed into some of the region’s most expensive ZIP Codes, including coastal communities such as Newport Beach, further complicating any return efforts, Mooney D’Arcy said.

“Land is everything to tribal culture,” she said. “So being landless is an impediment to full cultural realization.”

The Tongva land return comes during a moment when California is becoming conscious of its history of atrocities toward Native Americans.

In 2019, Gov. Gavin Newsom issued an apology for the state’s role in violence toward and displacement of Native Americans in California. The next year, Newsom signed an executive order that encouraged state agencies to look for opportunities for Indigenous groups in California to co-manage land or acquire “lands in excess.” In Monterey County, a 1,199-acre parcel of wilderness along the Little Sur River was returned to the Esselen Tribe in a $4.5-million deal with an environmental group.

Los Angeles County is also looking to improve access for Indigenous people to perform rituals in wildland areas, such as the gathering of indigenous plants for ceremonies.

The family of Alexander, the former property owner, built the home. She became interested in the transfer after learning of the land’s significance to the community and was referred to Tongva leader Jerry Lassos.

The donation was no small matter; the one-acre parcel was assessed at $1.4 million, according to county public records, and neighboring parcels are valued at more than $3 million.

Alexander, who owns homes in Torrance and Colorado, had been leasing the Altadena home to a tenant, and had asked only that the Tongva nonprofit pay for several months of lost rent before the transfer. Including legal fees and escrow fees, the Tongva community paid $20,000 for the parcel.

After initial efforts by the Ti’at society, a group dedicated to preserving the maritime traditions of the Tongva, community elders Julia Bogany and Barbara Drake asked for help from Cleaves, who had worked establishing the nonprofit that oversees the Kuruvungna Springs, a sacred Tongva site located on the campus of University High School in West L.A. that the group leases from the L.A. Unified School District.

Cleaves recalls walking the property for the first time, along with Drake, who has since died. They marveled at the towering oaks and the view of the expansive Eaton Canyon.

“Barbara said this is a place where we need to come together to be ourselves and where we can share ourselves,” Cleaves said. “It felt right — you could feel it, you could see it.”

During one of many cleanup days at the property, Cleaves remembered seeing a bobcat wander onto the property, stare at the group and run off.

“We have our animal relatives here with us, and we feel like they’re welcoming us back to the land, too,” he said.

After receiving nonprofit status in January, the Tongva Taraxat Paxaavxa Conservancy has relied on donations and support from Resource Generation Los Angeles and the Native American Land Conservancy, which led successful land-back efforts in San Bernardino County.

The nonprofit is looking at other land-back opportunities in both undeveloped and developed land, including affordable housing. Many members of the Tongva community who remain in Los Angeles have been priced out of their neighborhoods, said Cleaves, who called the present-day displacement from their ancestral land “a slow form of genocide.”

Johnson said some of her cousins have moved out of state because of high rents in Los Angeles. The conservancy is using the Altadena property to house a local Tongva artist who needs housing.

“If we were able to provide some type of housing opportunities for tribal members so that they can be reconnected with the land, that in and of itself promotes healing and well-being,” Johnson said.

For Tony Lassos, a member of the conservancy board, working to restore the Altadena property has helped him reconnect with his Tongva heritage. His great-grandmother, who died in the 1970s, was believed to be the last known speaker of the Tongva language.

But he grew up in a house that didn’t own its Tongva heritage. His grandfather, like many others in the “lost generation,” was harassed for being Native American while attending Indian boarding schools and had assimilated into white American culture.

“It’s really about rediscovering roots and creating a safe place for future generations of Tongva people to know where they came from and have opportunities that I didn’t have growing up,” he said.

Sitting with Lassos at a stone fire ring on the property, Kimberly Johnson and her daughter Samantha described how they were able to build a connection to their heritage through elders of the community, such as Drake.

When Johnson was a young mother, she wanted her children to grow up with more knowledge of Tongva culture. Drake welcomed Johnson, carrying her young son on her hip, into her home. Drake led them on hikes along the Santa Ana River and around Yucaipa and Idyllwild, teaching them Tongva plant knowledge.

“This wouldn’t be here without” Drake, said Samantha, gesturing to the property. “She’s still here.”

Lassos said Drake would always talk about the ancestors inside the trees.

“Anytime a wind goes through and the wind rustles, that’s her,” he said, pointing to the oaks.

A pair of red-tailed hawks flew overhead, a screech echoing throughout the canyon.

“It’s a good omen,” Johnson said as the group paused to watch the circling birds.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.