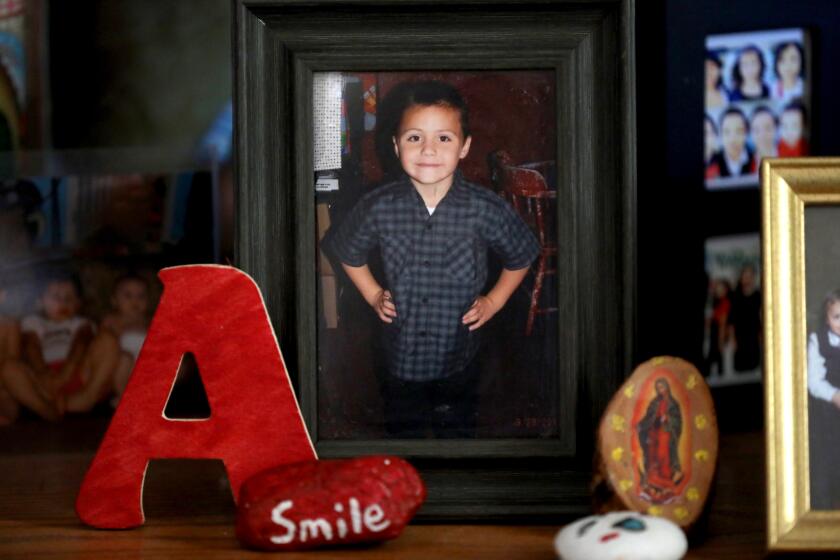

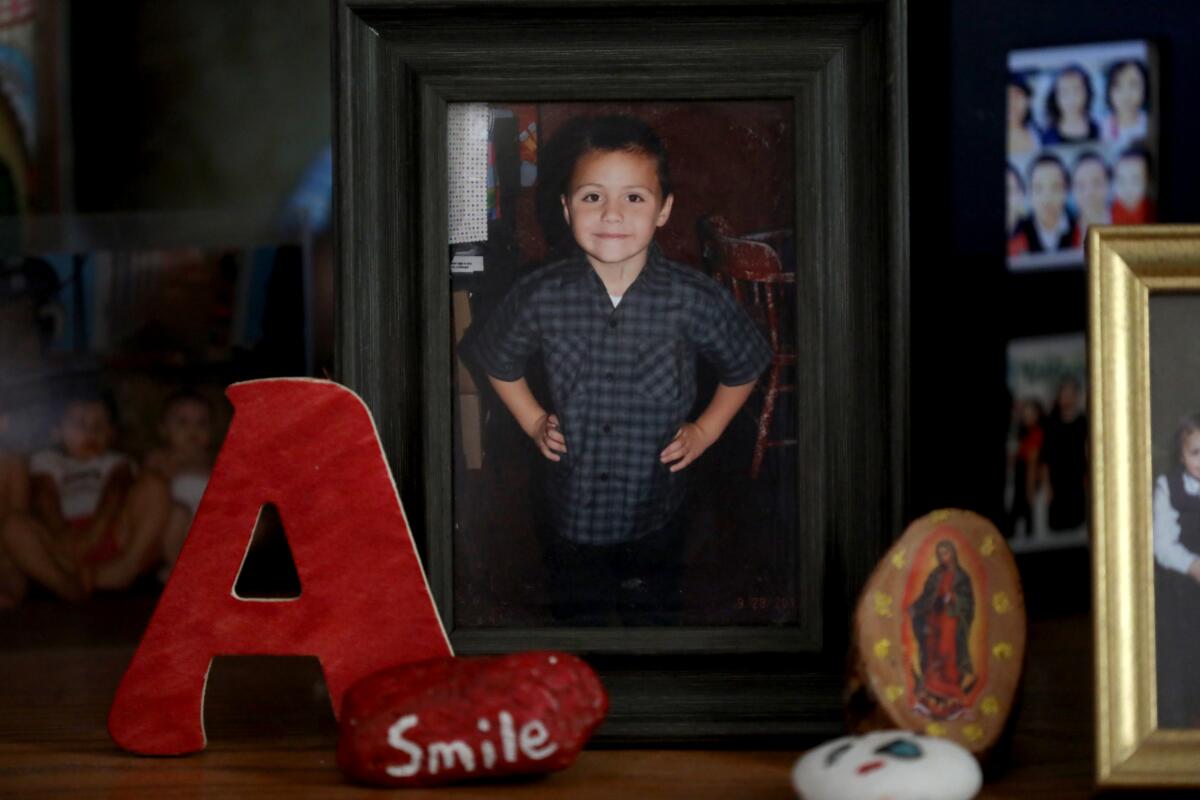

$32-million settlement approved in child abuse death of 10-year-old Anthony Avalos

- Share via

The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors on Tuesday approved a $32-million settlement for the siblings and father of 10-year-old Anthony Avalos, who prosecutors say died of abuse and torture at the hands of his mother and her boyfriend despite repeated warnings to social workers.

The five supervisors unanimously approved the settlement in the Lancaster boy’s 2018 death, which cast a shadow over the county’s Department of Children and Family Services. The child’s death came five years after Gabriel Daniel Fernandez, an 8-year-old Palmdale boy, was tortured and killed by his mother and her boyfriend while under social workers’ supervision.

The latest settlement is on top of a $3-million deal reached with one of the county department’s contractors, Pasadena-based Sycamores, which in 2015 provided home therapy for Anthony and was sued over allegations it disregarded concerns about abuse and failed to protect the boy.

In Anthony’s case, more than a dozen calls were made to the county’s child abuse hotline about his welfare — from teachers, counselors, family and police — yet child protective workers and others tasked with protecting him missed numerous warning signs and opportunities to intervene, according to an investigation published by The Times and the Investigative Reporting Program at UC Berkeley. Anthony’s life was sporadically supervised by DCFS from 2013 to 2017.

Brian Claypool, one of the lead attorneys representing Anthony’s relatives, noted that “the case was always about two things: in honor of Anthony to make social change and prevent this from happening again.”

Anthony Avalos’ mother and her boyfriend were sentenced to life for murder of the 10-year-old, which exposed shortcomings in L.A. County’s child welfare system.

“We will seek a new law ... that requires DCFS agencies statewide to deploy trained child forensic psychologists to interview a child outside the presence of parents when there are serious reports of physical/sexual abuse.”

He said that the law should mandate the sharing of abuse reports, including prior history, between social workers and therapists — something that did not happen in Anthony’s case — and that all therapists should be fully licensed, not interns, as was the case with Anthony.

“The amount of money paid will hopefully trigger this necessary change,” Claypool said.

The settlement resolved a wrongful death lawsuit brought by Anthony’s father, Victor Avalos, and three of the boy’s siblings, who also endured abuse at the hands of their mother and her boyfriend, according to their lawyers. Anthony’s mother, Heather Barron, and her boyfriend, Kareem Leiva, were indicted by a grand jury in 2018 on charges that they tortured and murdered Anthony and abused two of his siblings in the household. Barron and Leiva are being held without bail. Both have pleaded not guilty.

In May, with a civil trial about to begin against the county for negligence, fraud and civil rights violations, the county’s lawyers tentatively agreed to the settlement.

Barron and Leiva are awaiting trial in L.A. County, where prosecutors said the two poured hot sauce on Anthony’s face and mouth, whipped the boy with a looped cord and belt, and held him upside-down and dropped him on his head repeatedly.

At times, they withheld food and force-fed him, slammed him into furniture and the floor, forbade him from using the bathroom, and made their other children inflict pain on him, prosecutors said.

The vice principal of Lincoln Elementary School in Lancaster reported in 2015 that Anthony said his mother was beating him, locking him in a room with no access to food and subjecting him to squatting for long periods with his arms stretched out, a punishment dubbed “the captain’s chair.”

Anthony and his siblings also told their uncle about being locked in a room and getting whipped by a belt, prosecutors have noted in their case. At one point, the uncle physically blocked Anthony’s mother from picking up her children, which prompted a visit from L.A. County sheriff’s deputies. A deputy who responded to the scene also phoned the child abuse hotline and recommended that Anthony and his siblings not go home with their mother.

Nonetheless, Anthony was allowed to return to live with his mother that year. He remained with her despite successive hotline calls, including one from an employee at a domestic violence program who reported Anthony and his siblings had bruises and recounted that Leiva had forced them to fight one another.

On June 18, 2018, Anthony confided to his mother that he liked boys, records show. Barron told a DCFS caseworker that Leiva heard that conversation. The next night, Leiva repeatedly dropped Anthony on his head, according to grand jury transcripts. Anthony’s mother dialed 911 about noon two days later, and paramedics took the boy to a hospital in grave condition, where he died the following day.

A corrective action plan provided by DCFS to the supervisors said that in August 2020, it issued a revised policy when it comes to oversight of accountability in the Family Maintenance and Voluntary Family Maintenance programs and initiated a new training program to give social workers better interview skills and mandatory training for assessment tools that determine a child’s risk. Shortcomings in how social workers and sheriff’s deputies work together was also addressed in a March 2021 memorandum of understanding on collaboration and joint investigations.

The L.A. County Department of Children and Family Services is still haunted by three cases: Noah Cuatro, Anthony Avalos and Gabriel Fernandez.

One of Sycamores’ counselors, Barbara Dixon, was faulted by state regulators for failing to report suspected abuse in Anthony’s case. The state alleged that Dixon learned from Anthony that a relative had sexually abused him, and there was no indication from her notes that she had reported the suspected abuse.

Later that year, Dixon noted allegations from Anthony’s uncle that his mother was abusing him and his siblings, but there was no record that she had discussed this with DCFS.

Earlier this year, a state licensing board imposed a four-year probation on Dixon, a licensed marriage and family therapist, and required her to participate in psychotherapy, law and ethics training and coursework in child abuse assessment.

The state board had formally accused Dixon of failing to report allegations of abuse against Anthony in 2015 and against Gabriel Fernandez in 2013. Claypool said when he deposed Dixon in the civil lawsuit, she invoked her constitutional right against self-incrimination.

Times staff writer Matt Hamilton and Garrett Therolf, a former Times staff writer now at the Investigative Reporting Program at UC Berkeley, contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.