UC workers say they are struggling to survive in California, and fighting unfair system

- Share via

For doctoral candidate and single parent Konysha Wade, the financial struggle is daily.

More than half of her monthly earnings from her two on-campus jobs at UC Irvine goes toward renting her university apartment, where she lives with her 11-year-old son.

She brings home about $2,700 a month after taxes from working as an African American Studies instructor and a graduate student researcher — all while taking at least two classes toward her Culture and Theory doctoral degree and raising her son. She said their rent is more than $1,500 a month, which leaves just over $1,000 a month for all other expenses.

“It’s so, so tough,” Wade, 29, said. “We barely make it. We are trying to survive on limited savings. It’s about constant budgeting.”

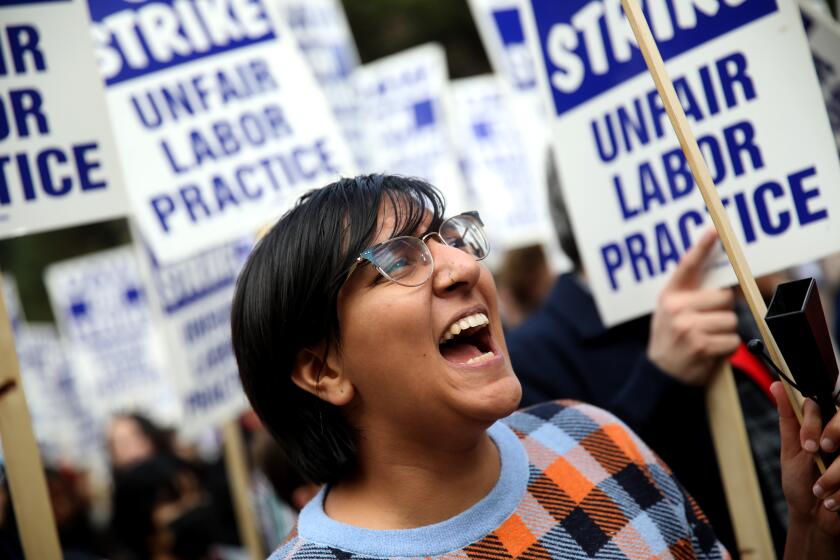

Wade is one of 48,000 University of California academic workers — including postdoctoral scholars, graduate teaching assistants and researchers — who walked off the job this week in a strike billed as the largest at any academic institution in history.

The work stoppage aims to challenge long-held labor practices at the UC and other universities across the country, which have come under growing scrutiny for how graduate workers and academic employees are paid in an era of rising inflation and growing union activism.

These workers perform much of the teaching, grading and research across the state’s most prestigious public university system.

About 48,000 academic workers across the University of California system remain on strike asking for better pay, childcare support and commuting subsidies.

In some ways, the strike underscores the growing economic strains low-wage employees are facing, particularly in places like California where the cost of living is high.

“People are already facing high rents and difficulty making ends meet on the type of pay they have,” said Paula Voos, a professor at the Rutgers School of Management and Labor Relations. “This is a time in which there’s a lot of organizing and a lot of strikes, especially by younger, lower paid workers who have been taking it on the chin for a while.”

Significantly increasing compensation for academic workers would definitely alter the budgets of big universities like the UC, where high tuition is already a big issue.

But strikers argue California has an opportunity to deal with the economic inequity — and set a better example for other universities.

“The university prides itself on our world-class research, yet it’s not evident in the paychecks it issues us,” said UC Irvine doctoral candidate Edward Mendez. “We don’t earn enough to live in the cities where these schools are.”

Union leaders are asking for large wage increases for academic workers, noting that housing costs on and near many UC campuses have continued to rise, making the majority of their members “rent-burdened,” or spending more than 30% of their income on rent.

The UC strike is calling for better pay and benefits for teaching assistants, postdoctoral scholars, graduate student researchers, tutors and fellows.

They want to see all graduate student workers — who are teaching assistants and tutors — earn a base salary of $54,000, more than double these workers’ average current pay of about $24,000, according to the union. For postdoctoral employees, the union has called for a minimum salary of $70,000, which would be, on average, a $10,000 increase, said Rafael Jaime, a UCLA doctoral candidate and president of United Auto Workers Local 2865, which represents 19,000 teaching assistants, tutors and other academic workers on strike

Surveys by the UAW found that 92% of graduate workers and 61% of postdoctoral scholars were rent-burdened.

“We need help,” Wade said as she joined her fellow graduate student workers and other academic employees on the picket line for the second day in a row. “We’re doing work that’s supposed to be contributing to the larger society — to liberate and to illuminate.”

UC officials have offered a salary scale increase of 7% the first year for certain graduate student workers and 3% each subsequent year — an offer that union leaders say falls short.

Ryan King, a University of California system spokesperson, said UC believes its current offers are sufficient. He noted most of these graduate employees are working part time while earning a graduate degree.

“Compensation is just one of the many ways in which they are supported as students during their time with the university,” King said.

But for Safa Hamzeh, a second-year international doctoral student in UCLA’s history department, that baseline salary is far from sufficient.

She said she makes about $24,000 annually working as a teaching assistant and lives in an apartment in the Palms provided by UC housing, paying $2,000 a month, split with a roommate. Because of her visa, she said she’s limited from taking on additional work.

For the record:

8:43 a.m. Nov. 16, 2022An earlier version of this article said Safa Hamzeh applied for CalFresh benefits to buy groceries. She applied for UCLA’s Food Box Giveaway Program.

To pay for food, she applied for UCLA’s Food Box Giveaway Program in order to get $100 to buy groceries at Kroger stores with her roommate. But even that wasn’t enough to cover the rising cost of groceries due to inflation, she said.

“I watched as grocery prices kept going up,” she said. “And that’s a thing that you need to do every week.”

Hamzeh was out on the picket line Tuesday at UCLA, especially calling for the university to drop the $15,000 nonresidential tuition fees that graduate student workers like her often face — though right now she has a fellowship that covers it.

“This is the strongest tool we have against the administration,” Hamzeh, 26, said. “When we are striking, we are not grading, we are not attending sections, we’re not attending lectures, we’re not holding office hours. When that happens, the entire education progress stops. … When we strike, you can see that we do most of the work because all of the work stops.”

Mendez at UCI said he wasn’t able to join the picket line Tuesday — despite his interest — because of his newborn baby’s nap schedule. The first-generation college student working toward his doctoral degree in visual studies at UC Irvine said he and his wife looked into utilizing campus childcare, but they couldn’t afford the $2,000 monthly fee — something unionized workers would like to see reimbursed for graduate and academic employees, like Mendez.

“I want to make sure that people don’t have to sacrifice their lives to go to grad school — and to get on the career path they want,” Mendez, 30, said. He pointed to the UC’s massive budget, which he said doesn’t correlate with the small payments to workers like him. He said while working on his dissertation, he teaches an introductory English class, earning about $25,000 for nine months of classroom instruction, prep work, responding to emails, office hours and grading.

He said both he and his wife supplement their day jobs — for him by co-editing the film section of a magazine based in New York, and for her, entering the gig economy filling Instacart orders.

Jaime said it isn’t rare to hear about graduate student workers and other academic workers struggling to make ends meet, trying to find supplemental jobs despite being already overworked. He said it’s especially painful to see the UC chancellors receive six-figure raises earlier this year, which the Board of Regents said was to provide “fair and competitive” compensation — something Jaime hasn’t seen apply elsewhere.

“When it comes to grad student workers and postdocs, for some reason that’s not translating to them,” Jaime said. “We’ve seen a pattern over the years as public universities have become more and more privatized, the value that scholars and researchers provide have been increasingly undervalued.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.