Legal settlement puts police agencies on notice about new use of deadly force restrictions

- Share via

SACRAMENTO — Days after Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a 2019 law meant to reduce police shootings, law enforcement union leaders began telling officers that the new policy didn’t really change much at all.

It did not put more stringent limits on when police can use deadly force, the president of one of the state’s most influential police unions wrote in a memo to its member agencies, and “will not significantly impact the way law enforcement performs their daily jobs,” according to documents made public with a recent legal settlement.

Alarmed by the “misinformation campaign” targeting the new restrictions on police use of deadly force, the American Civil Liberties Union sued the Pomona Police Department in July 2020 for adopting policies and training materials influenced by the union’s effort to undermine the law.

Under a settlement agreement reached last month, the Pomona Police Department will be required to train its officers on deadly force in compliance with the 2019 legislation that Newsom signed amid national protests against deadly police killings of unarmed Black men, including the shooting of a Sacramento man in his grandparents’ backyard in 2018.

Civil rights advocates hope the settlement will finally end the years-long disagreement over the importance of the law and send a warning to police departments around the state that they must comply with it or face legal repercussions.

“This settlement is important because it affirms that despite what these police lobbying groups might have been saying ... the law actually did change and the law changed to heighten the deadly force standard,” said Adrienna Wong, senior staff attorney at the ACLU of Southern California.

The law, known as Assembly Bill 392, says police can use deadly force only when “necessary in defense of human life,” a change supporters hailed as a pivotal step toward mitigating police shootings — but one that law enforcement critics deemed little more than a technical update of an antiquated state law.

Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta, who voted for the measure during his tenure in the state Assembly, said the settlement could provide more clarity on the law.

“No one should have a misunderstanding about what [AB] 392 requires,” he said. “To the extent that there was any misunderstanding or difference of interpretation by some in California, now that that’s clarified, that’s certainly a good thing.”

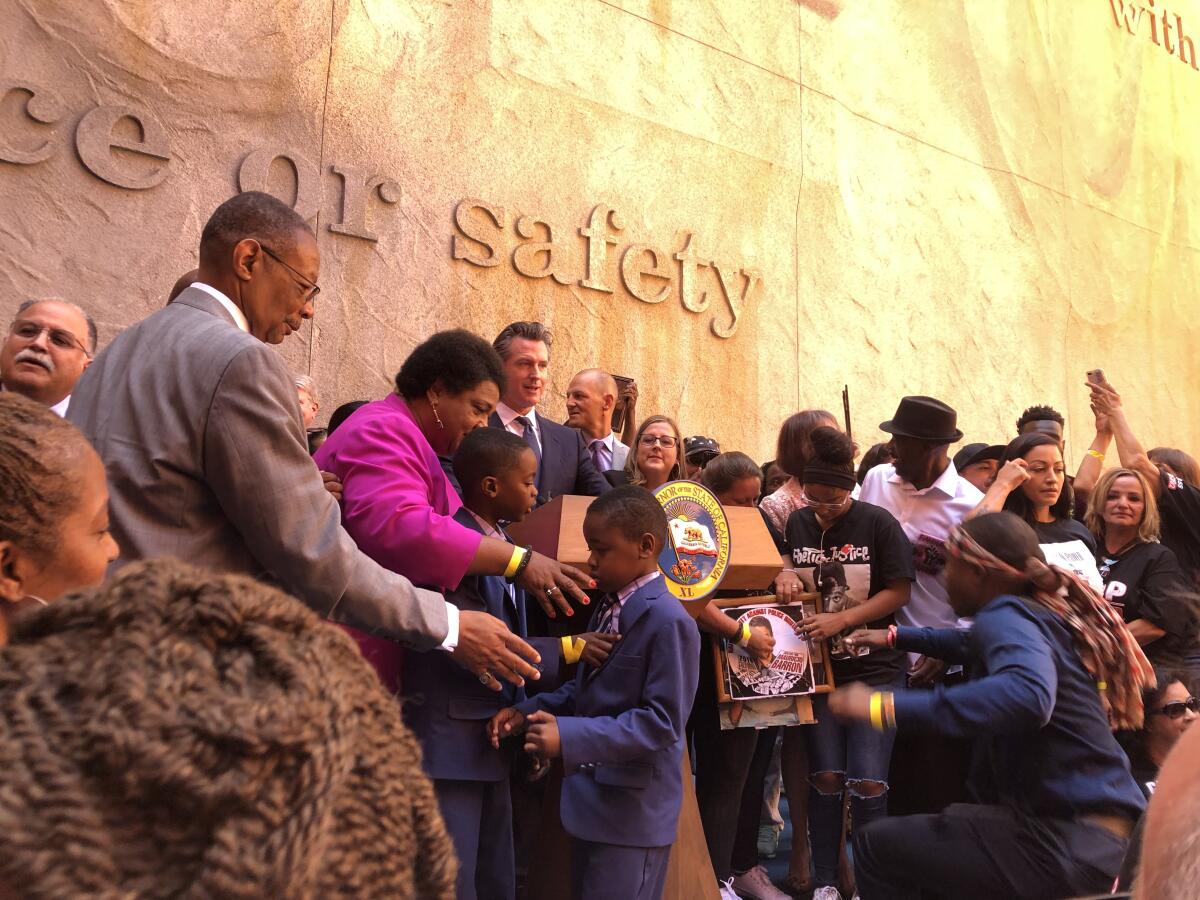

The battle over AB 392 was one of the Capitol’s most intense legislative fights of 2019. Families of police shooting victims routinely traveled to the Capitol to advocate for stronger restrictions against when officers can pull the trigger. Law enforcement groups raised serious safety concerns over setting what they described as an “impossible standard” for their members.

In the end, both sides claimed victory.

The proposal raised California’s deadly force standard from “reasonable” to “necessary” to preserve human life. But to broker a deal with police unions, legislators agreed to a set of amendments that included removing the definition of “necessary” in the bill’s final version, leaving that interpretation up to the courts.

With those changes, law enforcement groups said the bill maintained the “reasonable” standard and simply codified into California law two U.S. Supreme Court cases that dictate when and how deadly force can be used.

One of those cases, Graham vs. Connor, says deadly force is justified if a “reasonable officer” in the same circumstances would do the same thing, which has led prosecutors to focus only on the split second when an officer decides to shoot.

The new law includes elements of that case because it also is based on the perspective of a “reasonable officer.” But it requires prosecutors to consider both the behavior of the suspect and the officer that led to a shooting, a broader look at the circumstances that is intended to encourage de-escalation tactics and other strategies. An analysis of the bill determined it would “exceed the standards articulated and set forth by the U.S. Supreme Court.”

But Brian Marvel, president of the Peace Officers Research Assn. of California, sent a message to member organizations days after Newsom signed the bill claiming that advocates were “not successful in changing the standard to evaluate the use of deadly force from ‘reasonably objective’ to ‘necessary,’” and that the change wouldn’t significantly change current policing practices.

Lexipol, a public safety consulting company that counts many California police departments among its clients, also published a legal analysis of the bill that said while AB 392 included a few “benign changes,” the “good news” was that it maintained the “reasonableness” standard.

The ACLU said the misinformation quickly spread to departments across the state and led to poor training — including in Pomona — that violated the new law.

“Pomona Police Department officers have an erroneous view of the law regarding their use of force, and they carry this misunderstanding with them on an ongoing basis as they patrol the community while armed with deadly weapons,” the lawsuit alleged.

The Pomona Police Department did not respond to requests for comment. According to court records, top department officials claimed that officers were mandated to watch a video on the law’s requirements and that the agency had updated its use-of-force policy twice in 2020.

The settlement agreement requires the department to provide training on the “significant change in use of force threshold” and to update its use-of-force policy to reflect the elevated legal standard, which officers must sign in acknowledgment. It is also not allowed to use PORAC communications for formal training purposes.

Even after the settlement was reached, some law enforcement groups still maintained that the law didn’t make a sweeping change.

In a statement, Lexipol spokesperson Shannon Pieper said the company shared information with its customers that is “consistent with the language of the statute.”

Marvel declined to comment, but through a spokesperson he pointed to a letter PORAC’s lawyers wrote to him that reaffirmed the association’s legal position.

“PORAC stands behind our legal analysis that AB 392’s changes to the Penal Code largely codified the constitutional standards established by the courts and modernized the antiquated statutes in California,” the lawyers wrote.

The continued disagreement could signal future lawsuits.

Secretary of State Shirley Weber, who wrote AB 392 as a former assemblymember, said police organizations worked hard in 2019 to “nullify the impact of the bill.” The ACLU lawsuit helps “really drive home what the intent of the bill was, and what it did and what the language actually meant,” Weber said.

“I assume we will have to continue to do that,” she said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.