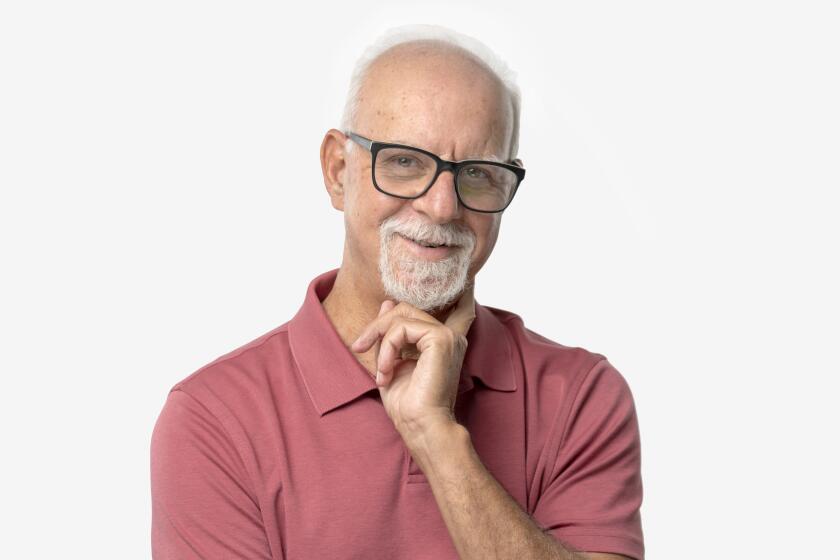

Column: Is 75 the right age to wait for death? Steve Lopez isn’t quite ready to pack it in

- Share via

The very idea of a stress test can be stressful. On my way to my appointment a few days ago, I wondered what the test might reveal about my heart, and whether the drugs prescribed for a recent diagnosis of atrial fibrillation are doing their job.

Closing in on 70, I don’t think about my own mortality every day, or about the fact that I’m almost due for a new pacemaker battery. But I’d just had a conversation with a high-profile physician and bioethicist — Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel — who recently repeated his vow, on national television, that when he turns 75, he’ll no longer take any life-extending medications or treatments.

That vow first surfaced in a provocative 2014 essay for the Atlantic. “By the time I reach 75, I will have lived a complete life,” Emanuel wrote.

No ventilators for Emanuel, a University of Pennsylvania oncologist who worked on President Obama’s Affordable Care Act. No heart valve replacements or colonoscopies. No chemo or radiation. Emanuel says he’ll take pass on flu shots, vaccines and antibiotics.

And no pacemakers or stress tests.

“We keep talking about average life expectancy … and it goes up and up and up, and we celebrate the up and up,” Emanuel said. But he believes that’s the wrong way to think about aging.

Emanuel, now 65, is more interested in a healthy and productive life than a long one. In his Atlantic essay, he skewered what he called the “American immortal.” That was his name for those who aim to be longevity outliers, even though mind and body decay is inevitable, quality of life diminishes, and loved ones may be burdened.

Golden State: Columnist Steve Lopez’s series on California’s aging population

“We wish our children to remember us in our prime. Active, vigorous, engaged, animated, astute, enthusiastic, funny, warm, loving. Not stooped and sluggish, forgetful and repetitive, constantly asking ‘What did she say?’ We want to be remembered as independent, not experienced as burdens,” he wrote in the Atlantic.

Geez, I’m already a little bit stooped. Are my loved ones whispering about me?

The article included a chart to support his argument that “by 75, creativity, originality and productivity are pretty much gone for the vast, vast majority of us.”

Boy, I guess I’m running out of time.

Seven years after his essay for the Atlantic — and just 10 years away from his expiration date — I called Emanuel after watching him double down on his vow in a recent CNN appearance. He told me that when he’s no longer working to make the world a better place, he has no desire to fight the inevitable just for the sake of lighting more candles.

There’s a focus in some quarters on trying to lift U.S. life expectancy — which dipped to about 77 because of COVID-19 deaths — to Japan’s average of 84. “But we shouldn’t be chasing Japan,” Emanuel argued. He said we should focus on lifting life expectancy in the U.S. for those who lag behind the average.

Emanuel doesn’t intend to do himself in at 75, and in fact he opposes euthanasia. He’s simply going to let nature take its course. I mentioned that I was about to get a stress test, and he seemed to think that was perfectly reasonable. I am, of course, a mere lad of 69. But at the moment, I can’t imagine refusing such a procedure 5½ years from now.

Get the latest in the Steve Lopez series "Golden State."

Join columnist Steve Lopez as he explores the challenges - and occasional thrills - of aging in California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

I do think, however, that Emanuel, who studied at Harvard and Oxford, is justified in calling out a culture that has trouble accepting death as part of life. When my father was in hospice care at 83 and refused a feeding tube because he’d already surrendered too much, I understood. There can be a fine line between extending life and prolonging death, and bravely, my dad was done with compromise.

At the time, I said I wouldn’t want to go on living if I were unable to handle my own basic needs, and I still feel that way for the most part. But as I age, and medicine evolves, I’m less inclined toward broad declarations about my own mortality or anyone else’s.

Emanuel, on the other hand, may not be genetically inclined toward understatement or humility. He’s the brother of Hollywood mega-agent Ari and former Chicago mayor and Obama chief of staff Rahm, the current U.S. ambassador to Japan.

Ben Franklin and former presidential medical advisor Anthony Fauci are exceptions to his age/productivity/worthiness thesis because they made valuable contributions to the world in their 80s.

“The Socratic view is that you want … an examined life,” Emanuel told me, “and what I was trying to do was encourage people to examine their lives when it comes to aging.”

All well and good. Except that people do examine their lives — on their own terms. There is no chart that can accurately measure human potential, and no simple formula for determining what is, or is not, a life of meaning and purpose. You don’t have to be Ben Franklin or Anthony Fauci to matter.

As the age wave circles the globe, and older people constitute a growing percentage of the population, aging is not always the liability Emanuel seems to think it is. And he comes close to fanning the flames of ageism, because some will see his words as a message that we’re essentially used up and disposable at 75.

“Chronologic age is a very poor yardstick to assess what treatment a patient can tolerate or benefit from,” said Dr. Andrew Chapman, a geriatric oncologist and director of the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center in Philadelphia. “Better to assess life expectancy, goals, and functional status in making these decisions.”

Since launching my Golden State column a month ago, I’ve heard from lonely, sick and financially struggling older adults, but also from hundreds of people who are fully engaged well past 75. Some have discovered new passions, devoted more time to family or thrown themselves into volunteer work; others have extended their careers or started new ones.

“For continued economic growth, development and productivity … we’re going to need people working into their 70s, 80s and 90s,” said Mike Hodin, chief executive of the Global Initiative on Aging, which works with business and healthcare leaders and policymakers to address the challenges and advantages of the world’s aging population. “There are not going to be enough young people to sustain society and our economic structures.”

We haven’t made much progress in curing memory loss, Hodin said, but great strides in fighting cancer and heart disease are elevating the chances of healthier aging. In 2014, Hodin responded to Emanuel’s Atlantic essay with his own commentary for the Huffington Post, titled “Why I Want To Live Past 75.”

“Rather than thinking of 75 as the time to die, let us continue to reimagine a 21st century life where 75 is a robust time of engagement and work,” Hodin wrote. “Perhaps for many … the start of yet another phase of life.”

That’s the thought I took to my stress test, where medical technicians tattooed me with electrodes and put me on a treadmill. Wires dangled from my body as the EKG printer whirred and the treadmill cranked me up, gradually, to a steep incline.

For a moment, I could identify with Dr. Emanuel’s aversion to life-extending indignities. But a big television screen had been placed in front of the treadmill, and it transported me to a gorgeous lake in Italy. It was as if I was taking a brisk stroll through paradise.

I have not been to that lake, and I’d like to fix that.

There’s so much I still want to do.

steve.lopez@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.