Thanks to the Supreme Court, California gun cases hinge more on history than modern threats

To best understand California’s desire to uphold its bans on assault weapons and high-capacity ammunition magazines, consider recent history.

In January, a man armed with a 9-millimeter MAC-10 with an extended magazine, a gun prohibited under state laws, massacred 11 people and injured nine others at a Monterey Park dance studio where mostly older patrons were celebrating the Lunar New Year.

Assault-style weapons that are banned in California were also used to slaughter 19 elementary school students and two teachers in Uvalde, Texas, in May, and five patrons of a queer club in Colorado Springs in November. Over the last decade, the same sort of guns were used in many of the worst mass shootings in the country, mowing down high school students and teachers, concert-goers and church parishioners, nightclub patrons and county employees.

However, in the high-stakes legal battles currently being waged over California’s bans in federal court — where decisions are anticipated soon — America’s gruesome modern history with the powerful weapons hasn’t been the focus. Instead, lawyers for the state and gun rights groups seeking to overturn the bans have been arguing over the relevance of much older laws governing very different weapons.

In the case over the assault weapons ban, recent filings have focused on a New Jersey law enacted in 1771 that prohibited people from setting up “trap guns” to fire at animals or intruders who tripped a rope.

In the case over high-capacity magazines, part of the focus has been on a New York law enacted in 1784 that limited to 28 pounds the amount of gunpowder that could be stored in any one place in New York City.

Such is the nature of recent litigation in a whole host of consequential gun cases — both in California and across the country — in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s monumental pro-gun rights decision last summer in New York State Rifle & Pistol Assn. vs. Bruen.

The Supreme Court’s overturning of a New York law restricting people’s right to carry firearms in public has reinvigorated a legal war on California’s gun laws.

In the Bruen decision, the high court took an originalist view of the Constitution and ruled that restrictions on firearms violate the 2nd Amendment if they aren’t deeply rooted in the nation’s history, or at least analogous to some historical rule. The high court also rejected another legal precedent, long relied on by states such as California in defending gun laws, that held that firearm restrictions could also be legitimate if they served a compelling state interest — such as preventing mass shootings.

While leaving space for restrictions with historical precedent, such as those against particularly “dangerous and unusual” weapons, the ruling nonetheless exploded modern American jurisprudence around gun control. It forced judges to start disregarding current government interests in passing modern gun control measures and had them focus instead on whether the framers of the U.S. Constitution or some other long-dead lawmakers had ever approved similar governmental limits on the right to bear arms.

Gun rights proponents have praised the Supreme Court’s reframing of the debate and its focus on the intentions of the Constitution’s authors. But others have blasted the high court as out of touch with reality and willfully blind to the tremendous violence such weapons could inflict if they are allowed to proliferate more than they already have.

“This new ‘history and tradition’ test that the Supreme Court established last June is wreaking havoc on America’s gun laws,” said Adam Winkler, a UCLA law professor who focuses on 2nd Amendment law. “Instead of having a reasonable debate over whether a ban on assault weapons is good policy or not, we have to debate whether a ban on assault weapons has historical antecedents.”

UC Berkeley Law School Dean Erwin Chemerinsky put it more bluntly: “It’s all about the absurdity of originalism.”

At stake in California

When the Supreme Court’s decision in Bruen came down, the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals had several legal challenges to California gun laws before it — and promptly sent them back down to the lower courts to be re-litigated there.

Three major cases — those to do with the assault weapons ban and the high-capacity magazine ban, plus a third over ammunition background checks — are all now before U.S. District Judge Roger Benitez, who is well known for his past rulings striking down gun laws.

A fourth 2nd Amendment case before Benitez involves a challenge to California’s ban on billy clubs. Other district court judges are reconsidering a second challenge to the assault weapons ban and a challenge to California’s law barring certain semiautomatic rifle sales to adults younger than 21.

In the four cases before him, Benitez ordered the state to identify historical laws analogous and “relevantly similar to” each of the laws being challenged.

The court ruled that a California ban on the sale of semiautomatic rifles to adults younger than 21 was unconstitutional.

In response, California Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta’s office conducted an exhaustive review of centuries of weapons law to prove that government restrictions are nothing new, especially when it comes to particularly dangerous weapons.

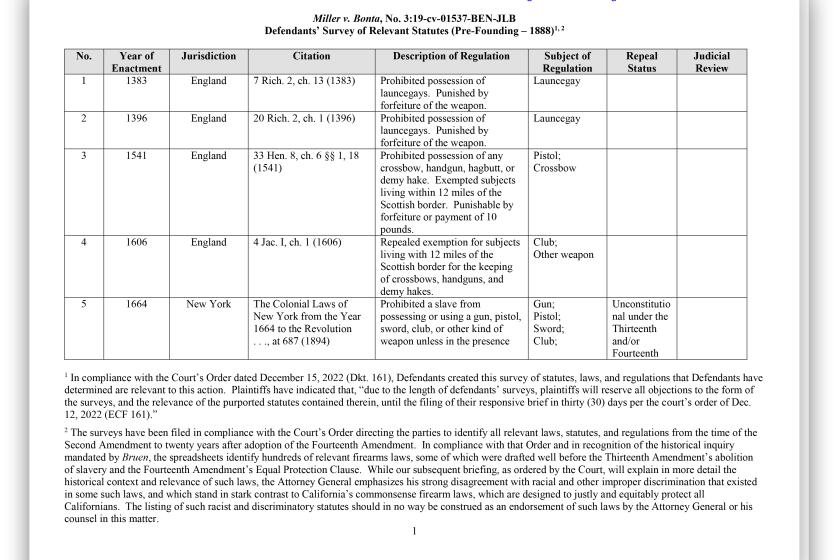

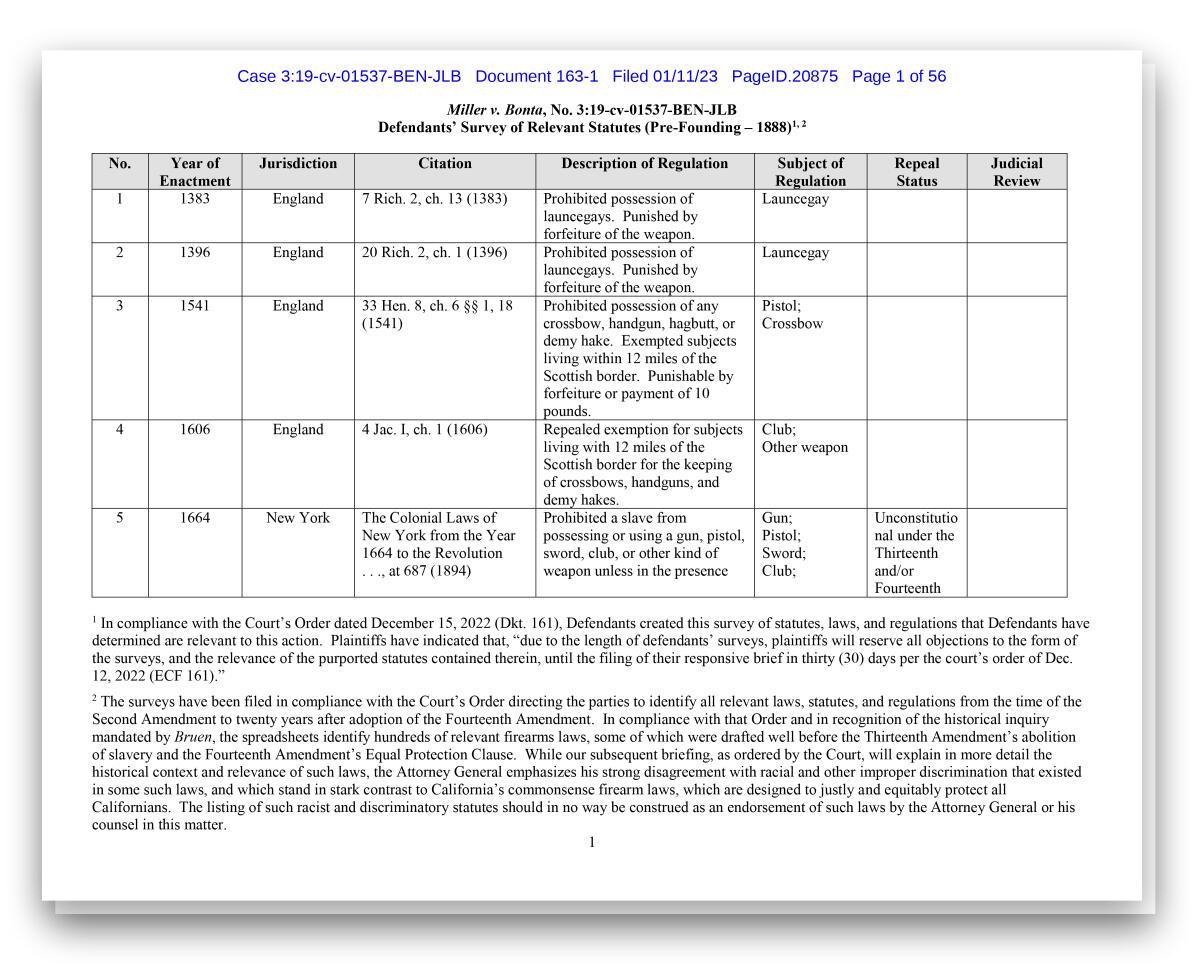

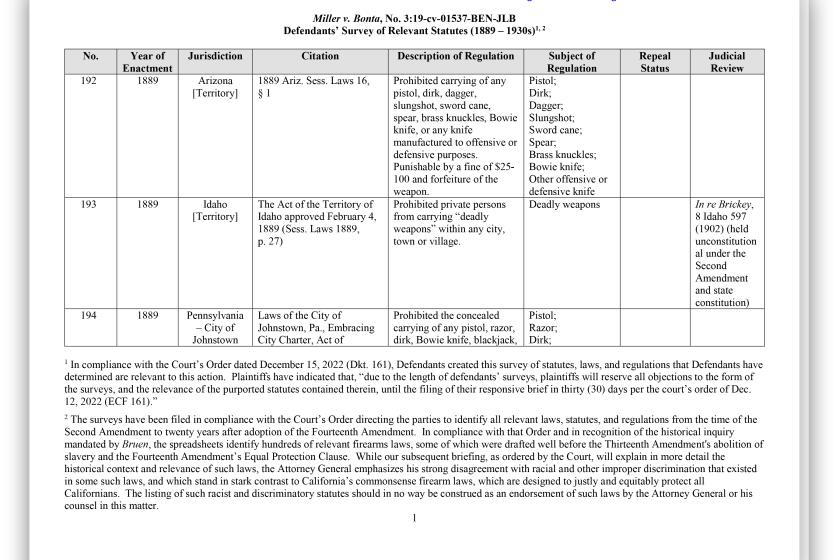

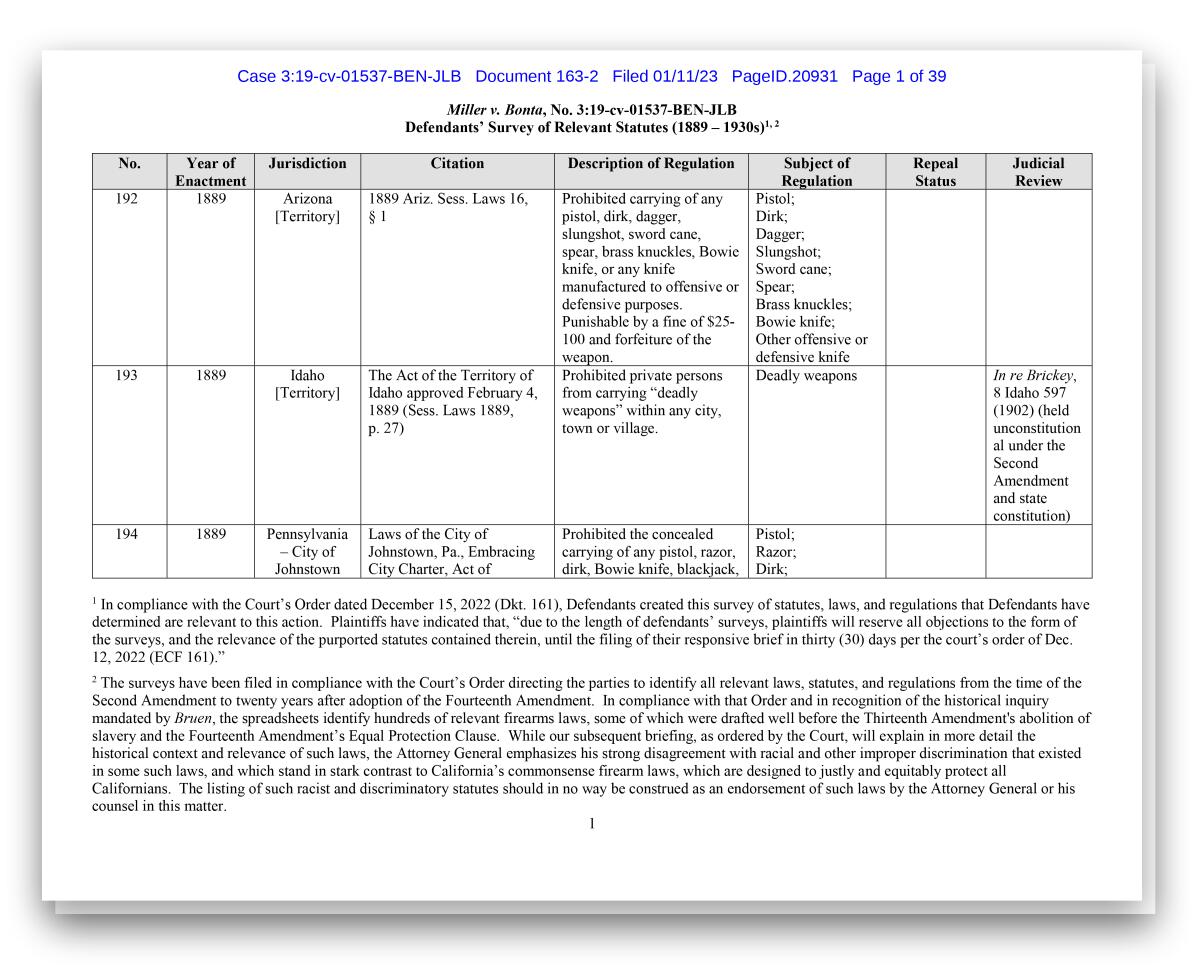

In the assault weapons case, Bonta’s office submitted two spreadsheets to the court outlining 316 different laws it considered relevant, starting with a 1383 English law that banned the possession of launcegays, or medieval throwing spears, and ending with an early 1930s law in Wisconsin that banned the possession of machine guns, hand grenades and other explosives.

The collection of laws, the state argued, showed that “governments have adopted laws like the challenged [assault weapons ban] consistent with the 2nd Amendment — restricting particular weapons and weapons configurations that pose a danger to society and are especially likely to be used by criminals, so long as the restriction leaves available other weapons for constitutionally protected uses.”

The state argued that its assault weapons ban, which has stood for three decades, restricts a specific category of weapons that are particularly dangerous, incorporate substantial technological advances from past weaponry, represent a relatively small portion of guns owned in America, are designed more for military-style offensive firing than self-defense and have played an outsize role in the devastating modern phenomenon of mass shootings.

In response, Benitez ordered the state to file another brief, this time limited to five pages and focused on only the most relevant historic law the state’s lawyers had found.

The state questioned the appropriateness of that exercise by noting the Supreme Court did not call for governments to find a single “dead ringer” for their modern law among historical statutes, but to show that their current law would have been consistent with historical readings of the Constitution and the 2nd Amendment.

“In assessing the constitutionality of a modern firearm regulation — especially in a case implicating ‘unprecedented societal concerns or dramatic technological changes,’ ” the state wrote, “... the historical analysis cannot be limited to the assessment of a single past law.”

Still, the state offered its lone analog: the 1771 New Jersey “trap gun” law. The state argued that law banned guns that had certain features attached to them — namely rope or string for tripping the traps. Likewise, it said, California’s assault weapons ban does not prohibit the possession of all semiautomatic rifles or pistols, just those equipped with certain accessories — such as a pistol grip or a flash suppressor.

“The burdens are comparably minimal because they restrict only ‘the manner in which persons may exercise their 2nd Amendment rights’ and do not ‘bar firearm possession completely,’ ” the state argued.

The coalition of gun rights proponents challenging the ban has offered vociferous rebuttals to the state’s arguments.

They have argued assault weapons banned by California’s law are “incredibly popular and common,” are not particularly dangerous and are used for self-defense. And they have said the historical analogs selected by the state were not analogous to the assault weapons ban at all.

The New Jersey ban on “trap guns,” for instance, was “far from a sufficient justification for California’s unconstitutional ban on common semiautomatic arms,” they wrote, because it “was a ban on conduct (the setting of a trap using a firearm), not a prohibition on the possession of a ‘dangerous unusual weapon’ or any particular set of characteristics.”

They also argued that the state’s repeated references to mass shootings were irrelevant to the discussion, given the high court’s Bruen decision, and that the notion that the nation’s founders couldn’t have conceived of mass shootings as they exist today was “simply history reimagined.”

“Knowing full well the potential of mass violence and killing, the Founders did not suppose that a greater government would provide an antidote,” the challengers wrote. “To the contrary, they enshrined the pre-existing right of the People to defend themselves against such evils into this Nation’s constitution and enacted an enduring bulwark against the government’s infringement of that sacred right.”

Similar back-and-forth debates have played out in the other California gun cases before Benitez.

What happens next

Legal experts who have been following the California gun cases have little doubt Benitez will rule against the state and declare the laws unconstitutional.

Benitez already declared the assault weapons ban unconstitutional when it first came before him in 2021, before the Bruen decision was handed down, in a decision in which he famously compared the AR-15 to a Swiss Army Knife.

In that decision, Benitez rejected the idea that firearms such as the AR-15 are particularly dangerous and unusual — which might justify a ban. He instead called them “average” weapons that are commonplace in American homes.

“The banned ‘assault weapons’ are not bazookas, howitzers, or machineguns,” he wrote. “Those arms are dangerous and solely useful for military purposes.”

In the same opinion, Benitez noted that AR-15 platform rifles are “ideal” for use by militias, which he said was another reason the ban ran afoul of the 2nd Amendment.

“Quite apart from its practicality as a peacekeeping arm for home-defense, a modern rifle can also be useful for war,” Benitez wrote.

Given that and other past rulings, experts believe Benitez is poised to overturn the California gun laws that are now before him thanks to Bruen — though it’s unclear when.

His won’t be the last word on the matter, however.

“He’s just a step in this process,” Chemerinsky said. “Benitez isn’t ultimately going to decide.”

For example, if Benitez strikes down the assault weapons ban, the state is expected to once again appeal the case to the 9th Circuit. And depending on the decision there, it could be appealed once more to the Supreme Court.

Bonta, in a statement, said the state’s gun laws have helped California reach “one of the lowest rates of gun deaths in the country” on a per capita basis, and his office will “continue to push forward” in its efforts to save lives.

“The 2nd Amendment is not a regulatory straitjacket,” he said. “States have the power to protect their communities and provide reasonable safeguards to allow citizens to carry out their business and live freely.”

Legal experts are skeptical the assault weapons ban will fare well if it does reach the Supreme Court, but they aren’t as uniformly convinced about the outcome there as they are with Benitez.

Eugene Volokh is a UCLA law professor who teaches about gun regulations. He has done consulting work in the past for the Firearms Policy Coalition, which is one of the plaintiffs suing to overturn the state’s assault weapons ban, but he has not worked for them on that case.

Volokh said assault weapons as defined by California can be dangerous and deadly, just like all guns. But he questioned whether they are any more deadly or dangerous than other guns that are not banned. And that — along with the fact that they aren’t particularly unusual in the U.S. — probably negates any argument for upholding the ban that isn’t based on a more precisely analogous historical law, he said.

Whether the courts will consider any of the hundreds of historical laws that California has cited as sufficiently analogous to make the ban constitutional under Bruen remains to be seen, Volokh said.

UCLA’s Winkler said assessing modern gun laws based only on whether a similar law existed in the distant past may be absurd, but it’s how the law works now because of Bruen — and “the path for the assault weapons ban and several other California gun laws is not promising.”

Benitez was correct in finding that assault weapons are common in American society, Winkler said, and that undermines any argument that they are both dangerous and unusual.

“Dangerous and unusual are two different things,” Winkler said. “It’s hard to say these guns are not in common use for lawful purposes. Recreational shooters across the country have bought millions.”

Chemerinsky said he believes there is a strong legal argument that assault weapons, as defined by California, are particularly dangerous and subject to regulation, and he hopes the higher courts will see it that way too.

To suggest an AR-15 is like a Swiss Army Knife is not only wrong, he said, but offensive to the families of those murdered by such firearms.

“AR-15s are military weapons to kill a lot of people in a short amount of time,” Chemerinsky said. “There was no weapon in 1791 that could kill so many people so quickly.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.