Wanna throw a block party in L.A. County this summer? Start here

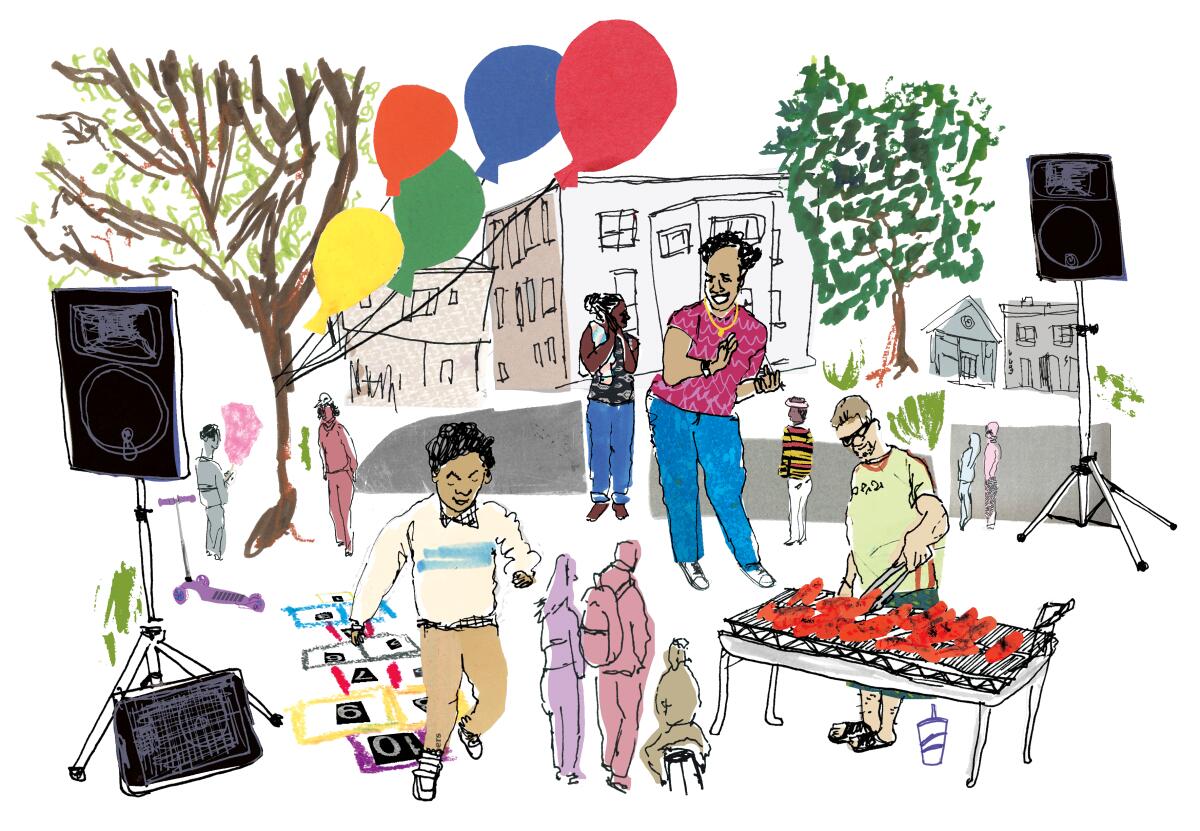

It’s a sunny day and the smell of carne asada is wafting from the grill. Kids are racing up and down the block on their scooters, and your neighbors are gathered in conversation.

You’re envisioning a block party.

The name explains it all — one block is closed to traffic so the neighborhood can come together.

The block party’s origin story is in New York, first held to bid a celebratory farewell to neighborhood soldiers leaving to the First World War. They’ve been neighborhood staples since — and even have a place in the founding story of hip-hop.

It seems as though something that ingrained in American culture would be easy enough to organize, gathering your neighbors in the street for an afternoon. Unfortunately, it’s a little complicated. In Los Angeles County, you have to get permission from your city — if your city even allows this type of event — and make sure your neighbors are on the same page.

The latter might be tough, considering most Americans don’t even know their neighbors.

A 2018 Pew Research Center study found that about 24% of urban and 28% of suburban dwellers know all or most of their neighbors, compared with 40% of residents in rural communities. And even though more rural residents know their neighbors, Pew found that didn’t mean they interacted with them more. The study also discovered that among Americans who reported knowing at least some of their neighbors, 1 in 4 said they have face-to-face conversations with them at least several times a week.

Learn who to talk to in government when you want to get things done in your neighborhood. Get involved in your L.A. County community with the help of our people’s guide to power.

A lot has changed since those data were published five years ago. So if the pandemic has inspired you to get to know your neighbors — to build community and to be resilient in the face of an emergency — what better way than to throw a block party?

The Times contacted all 88 cities in L.A. County, as well as the county itself to account for unincorporated areas, to find out the rules for hosting block parties. Here’s what you need to know to get started.

The basics of hosting a block party

A majority of cities in Los Angeles County allow block parties. Cudahy, Downey, Glendora, Lancaster, Rolling Hills, Santa Clarita, Santa Fe Springs, Walnut and West Hollywood do not.

Some cities don’t have a specific permitting process for block parties but will work with you on getting permission, except for San Dimas. But that shouldn’t stop interested party planners from starting the conversation with San Dimas; residents can contact City Hall.

The City of Industry, which is mostly commercial and has a population of less than 300, said it has never had a block party.

Some cities don’t allow block parties on certain streets. For example, Redondo Beach doesn’t allow block parties on Hawthorne, Aviation, Redondo Beach and Torrance boulevards (check the city website for the complete list). Other cities, such as La Mirada, don’t allow block parties unless it’s in a cul-de-sac on the Fourth of July.

In cities that do allow block parties, hosting one starts with a conversation among your neighbors.

Knock on people’s doors, leave a note with your contact information or start a group text message — whatever method of communication makes you and everyone else comfortable.

It’s ideal to get a positive consensus on having the party and setting a date. Those are two crucial pieces of information you’ll be providing to your city government — some cities will require you to collect signatures from a certain percentage of your neighbors, or all of them, before approving the party.

When your group picks a date, keep in mind that most cities require at least 30 days’ notice.

Depending on each city’s process, you might be filling out an application for an encroachment, block party, temporary use, special event or street closure.

Whatever the permit is called, it’s typically not free. Some cities charge a few hundred dollars; Bell’s fee is the highest in the county at $900, followed by West Covina at $800. Some cities allow you to request or petition for a fee waiver or subsidy.

If that doesn’t give you sticker shock, maybe knowing there are additional costs to hosting a block party will. A majority of cities require that you purchase event liability insurance. Event insurance can help protect you from financial loss as a result of liability for damages, injuries and accidents at your gathering, said Teny Josephbeck, a member of the Allstate Insurance Co. media team.

“As an event organizer, you should check for limits and coverages required by the city in which your event is being held to ensure that you have adequate protection,” Josephbeck said.

Event insurance can be purchased with your homeowner’s insurance or separately and costs about $100, depending on the provider.

Other costs can include renting barriers to block traffic and in some cases law enforcement or traffic control.

And that’s all before you rent tables and chairs and buy food!

The city of Azusa, which does not offer a way to waive or subsidize its $222.50 permit fee, suggested asking participating neighbors to chip in what they can toward funding the event.

Looking for ways to get involved in your neighborhood and community? Maybe you just want to have an abandoned couch hauled away? Shape Your L.A. can help.

The state of block parties in California

David Galaviz, USC’s associate vice president of government and community relations, works closely with students to help them get permits from the city of Los Angeles to host holiday-related or fundraising events in the street.

The students are going through the same process L.A. residents would to host a permitted block party. Galaviz said they have to work with different city departments to get approvals and permits and to pay associated fees, as well as communicating with the surrounding neighborhoods.

The biggest barrier, he said, is cost. Second is the complexity.

“No offense to the city or any local government, but it’s also just the larger the city, the harder it is to get these permits, in my view,” he said.

So the trend Galaviz is seeing is that block parties are going from being organically organized by neighbors working together to being more professionally planned by nonprofits or others outfits that can devote more time and resources to an event.

“It’s the same intention. It’s that they’re designed to bring people together and provide that kind of feeling of community,” he said.

There is one city in Sacramento County that’s working to make block parties simpler.

Citrus Heights, population 80,000, launched its block party trailer program in February.

It was able to do so with a portion of a $15-million grant awarded to the city under the American Rescue Plan.

Very early on, the city committed to using that funding to advance the community’s shared goals, said Meghan Huber, economic development and community engagement director for the city.

Huber said the city conducted a lot of community outreach to define residents’ priorities, and it came down to four things:

- Community image (preventing homelessness, blight abatement and beautification).

- Economic development.

- Infrastructure.

- Community connection.

“As we were coming out of COVID, we had really conclusive data that our community was hungry to reconnect and have fun together,” Huber said.

That’s where the block party trailer program comes in, with Citrus Heights finding inspiration from similar programs in Arizona and Texas, Huber said.

The program had two things the city wanted that would encourage neighborly engagement: accessibility and ease. So Citrus Heights created three easy steps — a one-page reservation application and $500 refundable deposit; applying for a street closure permit (if the event is in the street); and event insurance that can be acquired through the city’s risk management division.

The fun part, Huber says, is what’s in the trailer. It’s equipped with tables, chairs, trash receptacles, coolers, a sound system, pop-up tents, barricades and yard games. All residents need to worry about, after the permitting process, is bringing the people and the food.

Since its program launch, Citrus Heights has had one reservation for the trailer. Huber said the city is finding that even though they have this accessible tool, they’re still working on building awareness.

“You can’t just launch it in a vacuum and expect it to be fully utilized, so for us it’s still something that we’re working on amplifying every day,” she said.

About The Times Utility Journalism Team

This article is from The Times’ Utility Journalism Team. Our mission is to be essential to the lives of Southern Californians by publishing information that solves problems, answers questions and helps with decision making. We serve audiences in and around Los Angeles — including current Times subscribers and diverse communities that haven’t historically had their needs met by our coverage.

How can we be useful to you and your community? Email utility (at) latimes.com or one of our journalists: Jon Healey, Ada Tseng, Jessica Roy and Karen Garcia.

More to Read

About this article

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.