EXETER, Calif. — The citron is an unusual fruit.

It’s an ancient citrus varietal, one that’s lumpy, wrinkly and somewhat oblong.

You won’t find it in most grocery stores. It’s not a La Croix flavor. It isn’t showing up on many cooking shows.

But it is special.

For thousands of years, the citron has been a part of the Jewish holiday of Sukkot. A vital element of the tradition, the fruit is held while reciting a daily blessing during the weeklong harvest celebration, which this year begins Friday at sundown.

For the last 40 years or so, many Jews in America have been celebrating with citrons grown by a single large U.S. supplier: Lindcove Ranch. To cultivate this esoteric fruit, the San Joaquin Valley farm complies with various Jewish agricultural laws and gets every relevant approval from a kosher supervision service.

Greg Kirkpatrick, who operates the Exeter, Calif., farm, is not Jewish. He’s Presbyterian — and he hasn’t been to church lately. This year, though, he’s been tested like a figure from the Bible — Old Testament, New Testament, take your pick.

On a recent weekday afternoon, Kirkpatrick eyed a row of spindly citron trees whose branches were supported by a network of trellises and twine. He fingered a waxy shoot. Kirkpatrick, 62, wasn’t pleased. Far from it.

As head of his family’s specialty citrus farm, Kirkpatrick has dutifully tended to this crop. Despite those efforts, the trees — thrown out of whack by the epic rainstorms that throttled this part of California starting in January — were not cooperating. By March, they should have been covered in flower buds. There were none.

“That’s when I started to worry,” he said.

After two more agonizing months, the still-dormant trees forced Kirkpatrick to consider a dark and increasingly likely possibility: a year with no harvest. The prospect filled him with existential dread.

“I had a full identity crisis over that,” he said.

Finally in charge after 20 years on the farm, Kirkpatrick could now understand what his late father must have felt when he weathered the tough times that any family operation faces. The sense of responsibility. The anxiety. The angst.

Kirkpatrick just needed the trees to do their part. Would they?

Among Jews, a citron is known as an etrog, the fruit’s Hebrew name. Ahead of Sukkot, they can cost more than $100 apiece, owing in part to their rarity and the stringent rules that govern their cultivation and use. (Sample dictate: To be deemed kosher for Sukkot, an etrog must be free of any major blemishes — no insect nibbles allowed.)

In a typical year, Lindcove Ranch’s business partner, the Lakewood, N.J.-based etrog distributor Yaakov Rothberg, would visit the farm over the summer to inspect the citrons. Using a scale that tops out at 7.7 — a quirk befitting the byzantine etrog ecosystem — Rothberg and a few colleagues grade the fruit, taking into account each citron’s size, color and overall aesthetics. (Generally, the bumpier the better.)

Sensing calamity, Kirkpatrick had summoned Rothberg to the farm in May. They walked the rows of barren citron trees. Rothberg remembers what he was thinking on that day: “We’re done.”

“I’ve been doing this for decades,” he said, “and I’ve never seen anything like it.”

Citrons are Lindcove Ranch’s biggest income-producing crop, accounting for about a third of its annual revenue. With 14 employees working only 35 acres — among the smaller self-sustaining commercial farms in the valley’s citrus belt — the facility heavily depends on the etrog business. In turn, a vast web of retailers and wholesale buyers were counting on an allotment of Lindcove Ranch citrons.

And there was another stressor: Kirkpatrick was grieving. In late February, amid the cascade of rainstorms, the farmer’s father, John Kirkpatrick, died at the age of 92. He’d started Lindcove Ranch with his wife, Shirley, more than 50 years ago. He’s the one who plunged the farm into the etrog business decades ago. “Straight-up mensch” is how Rothberg described the lifelong Presbyterian of Scottish descent.

Not sure what to do on Yom Kippur? In L.A. you’ve got options. Climb a mountain, go to the beach, call your loved ones — whatever helps you get into a space of self-reflection.

Kirkpatrick said that at the time of his father’s death, the biblical deluge was seen as a blessing — not a harbinger of crisis.

“We didn’t really even know, at that point, what the impact was going to be,” he said. “It was great; we were getting rain!”

A citrus gambit

So how does a family of Presbyterians from the Central Valley wind up growing a niche citrus fruit that has been part of the Jewish tradition going back millennia?

Big Ag.

John Kirkpatrick, who’d established Lindcove Ranch in the mid-1960s, had for years been a grower of lemons, oranges and other fruit. But the increasing industrialization and consolidation of citrus farming made it harder to compete with larger enterprises, Greg Kirkpatrick said.

It was an out-of-the-blue telephone call from a part-time etrog importer named Yisroel Weisberger in 1980 that would change the course of John Kirkpatrick’s life — and give his farm a new vitality.

Weisberger asked Kirkpatrick if he could help him find a grower to cultivate citron trees. “And I said, ‘I think you’re talking to him,’” Kirkpatrick told California Bountiful, which is published by the California Farm Bureau Federation, in 2018. “I saw it as a challenge.”

Farming citrons did turn out to be quite challenging, said Shirley Kirkpatrick, 88. For starters, she said, “We just thought they would probably grow like lemons.” (They were wrong.)

But over time, the Kirkpatricks learned to tend to the trees, whose branches must be secured to trellises, lest the heavy fruit pull them to the ground. When Rothberg, who is Weisberger’s brother-in-law, took over as Lindcove Ranch’s distributor in the mid-’90s, he brought consultants from Israel to help improve the operation, which now grows five citron varieties.

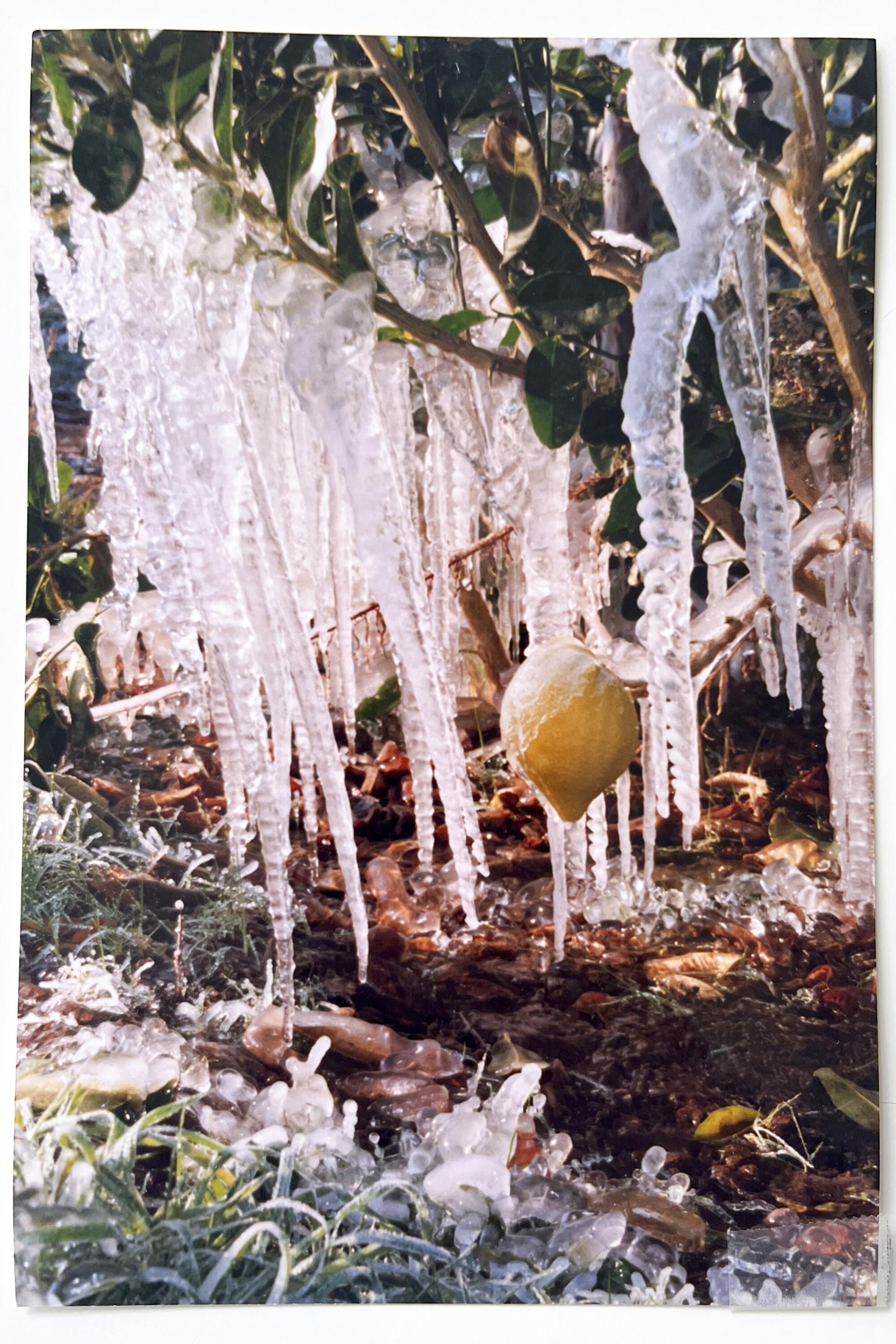

Still, there were tough times, Shirley Kirkpatrick said, including a 1990 freeze that wiped out the whole crop. “A couple of times, John would say, ‘I think we are going to quit,’” she said. “And Yaakov would say, ‘You can’t!’”

But the difficulties they faced — contending with uncooperative weather, decoding obtuse Jewish agricultural law — ensured that “we were the only ones who could do it” in the U.S., Shirley Kirkpatrick said. “There were a few wannabes along the line, but ... they didn’t make it.”

There are some small citron farms scattered across the country — they typically grow the fruit for its use in candy, marmalade and liqueur. (Lindcove Ranch sells citrons with cosmetic defects to makers of these products.)

Eventually, around 2000, John and Shirley Kirkpatrick made plans to bring their son into the business.

Greg Kirkpatrick was then working for American Farmland Trust, an agricultural organization dedicated to conservation. The job was fulfilling: In 2002 he helped establish a four-mile-long “farmland security perimeter” in Madera, Calif., protecting the area from development in a clash that was covered by The Times. But, in 2003, his father called the family together — Kirkpatrick has two siblings — for a momentous meeting. It was then, Greg Kirkpatrick said, that he was tapped to one day take over Lindcove Ranch.

The process wasn’t complete until John Kirkpatrick’s passing.

Childhood trauma levels are high and college rates are low in rural California. What’s that mean for a high achiever?

It hadn’t always been easy working for his father, Greg Kirkpatrick said. At times, the patriarch wasn’t inclined to relinquish control. At the end of his life, though, he told his son what he needed to hear.

“He said, ‘It is all yours, you’re ready to do it. Take the reins,’” recalled Kirkpatrick, growing emotional. “That was very important to me.”

‘Gratitude to God’

Kirkpatrick has, over the years, learned a good deal about Judaism. Especially Sukkot.

Jews mark the holiday by building temporary huts where they eat their meals, and sometimes even sleep, throughout the celebration. The dwelling, known as a sukkah, is meant to call to mind the impermanent shelters of the Israelites as they wandered in the desert for 40 years, because what would a Jewish holiday be without a little ennui?

Still, Sukkot is a joyous occasion, one that is centered on four plant species: the myrtle, willow, citron and date palm, whose frond is known as the lulav. Each represents a different part of the body — and “the etrog is the heart,” said Rabbi Asher Brander of LINK Kollel, an Orthodox congregation based in Los Angeles’ Pico-Robertson area.

The four species, he said, represent “the totality of a human being who is coming and expressing gratitude to God.”

Joel Rembaum, rabbi emeritus of Temple Beth Am, a Conservative synagogue on La Cienega Boulevard, said that Jews seek out aesthetically pleasing etrogim — that’s plural for etrog — as a way to beautify “a divinely ordained religious practice.”

“It is not to outdo the person next door,” he said. “It is the beautification of the mitzvah — a recognition of the beauty that God provides.”

As part of Sukkot, the four species are held while saying a daily blessing — except on Shabbat — that is an expression of the holiness of the holiday. During the ritual, the four items are shaken in six directions: north, south, east, west, up and down.

Rabbi Susan Goldberg of Nefesh, a transdenominational congregation that offers Shabbat services in Echo Park, said that “when you are holding the lulav and etrog, you remember we are an ancient people very much connected to the Earth.”

Kirkpatrick knows at least some — if not all — of this. He’s held the four species in his hands. He’s said the Hebrew blessing.

As he learned about Judaism, Kirkpatrick picked up the lingo — and a very particular way of saying it. Some Orthodox Jews of Ashkenazi descent speak a version of Hebrew influenced by Yiddish that renders a T sound as an S.

When, for example, Kirkpatrick talks about an etrog, he calls it an “esrog.” Hearing a scruffy farmer of Scottish stock speak Hebrew words like a black-hat-wearing rabbi from the Old Country illustrates the cultural exchange taking place at Lindcove Ranch.

While not a Jew, Kirkpatrick said that he feels a strong spiritual connection to Judaism.

“How can you not when you have thousands of Jews praying for you on Tu B’Shevat?” said Kirkpatrick, referencing the Jewish holiday that celebrates trees. “[They’re] praying for a beautiful esrog for you. You feel that.”

He needed those prayers this spring.

The harvest, finally

One day in late May, Kirkpatrick went to inspect one of his citron orchards. The farmer, who moves among the trees and tangled weeds with a sure-footedness that approaches grace, spotted something unexpected.

Flower buds.

There was elation. Then, a realization. It wouldn’t be a “full bloom,” Kirkpatrick said. Some trees that had produced hundreds of citrons a year earlier didn’t make any fruit at all — “complete blanks,” he called them. But it was enough to warrant a harvest.

“We can’t just let it go by the wayside,” said Kirkpatrick.

The harvest began in August, about a month behind schedule. The crop was too small and too late to justify a trip from Rothberg and his colleagues to inspect the citrons at the farm and assign them grades. That work, which can enhance the value of the most aesthetically pleasing fruit, would instead be done in New Jersey.

By this time, Kirkpatrick and Rothberg had already decided to purchase citrons from a farm in Israel — where most of the world’s major etrog growers are located — to ensure they’d have enough to honor commitments to their customers. That foreign fruit would supplement the citrons from Lindcove Ranch. It was a tough monetary decision, but it had allowed them to hedge in case the harvest didn’t work out as expected.

Kirkpatrick knew in mid-September that he would be able to hit the production numbers he’d forecast for Rothberg. The harvest amounted to about 30% of last year’s haul, he said. The business operates on a consignment model, with Lindcove Ranch getting a cut of each etrog Rothberg sells.

“We will pay back all of our expenses and have a little bit left over,” Kirkpatrick said.

There was at least one unalloyed positive: The fruit, Kirkpatrick said, was the highest quality produced by Lindcove Ranch in many years. The citrons lengthened to a desired shape, and they had a waxy shine.

What did he attribute the strong results to?

“My dad,” Kirkpatrick answered.

He said this with a laugh. But it didn’t seem like a joke.

An ‘inflection point’

On a mid-September day that would reach 94 degrees, Rabbi Avrohom Teichman, clad in slacks, a dress shirt and tie, stood amid Lindcove Ranch’s citron trees and admired the fruit that he’d selected.

Once back home in Lakewood, N.J., the rabbi would distribute the citrons to family. He hadn’t chosen any of the big honkers that Kirkpatrick said can fetch $1,000 apiece.

The etrogim were ensconced in a foam case that had been designed by Kirkpatrick to offer maximum protection to the fragile fruit. The most delicate part of an etrog is its pitom, an easily broken protrusion on one end of the fruit that is a remnant of the flower bud from which it grew. (If a pitom falls off naturally — and it often does — the etrog is still kosher; if it is otherwise removed, forget about it.)

The rabbi wasn’t just at the farm to shop. He was on hand to observe an important task: the transfer of citron cuttings from small plastic sleeves to larger containers so they could continue to grow. Even as the harried harvest continued, Kirkpatrick paused that work to perform this essential undertaking, which had been engineered by Lindcove Ranch to speed up a natural process.

It takes five or or six years before a citron tree grown from seed produces usable fruit. But a tree that grows from a cutting taken off another will bear citrons in about three years. That’s an especially convenient duration, because Jewish law dictates that etrogim must come from trees that are more than 3 years old. Younger fruit, known as orlah, may not be picked.

The delicate cuttings, taken in early August, spent about a month in a greenhouse. “They are little babies so they need special treatment,” said Teichman, 77, the rabbinic administrator of Kehilla Kosher, a nonprofit that provides kosher supervision services.

An unlikely pair of Southern California businessmen paved the way for the sushi revolution in Los Angeles, upending American dining — and their own lives.

To comply with orlah rules, Teichman said, the cuttings must never be “disconnected from the ground” during their transfer. If they were placed on, say, a linoleum floor before being replanted, the three-year waiting period would have to be restarted. Teichman needed to confirm that the cuttings were properly transferred without losing their connection to the earth. He also had to check the would-be trees’ lineage — each had a small label that detailed its extraction — to make sure they had “a pure pedigree.”

As Teichman looked on, a few farmhands gingerly coaxed the cuttings out of the plastic sleeves, exposing young roots tangled in clods of soil. They were then placed in new, larger containers.

One of the workers, Mari Castaneda, said that she’d never even seen a citron before starting at Lindcove Ranch last year. The work is better — and more interesting — than harvesting grapes, she said. Along the way, she’s learned a bit about Judaism.

“I knew nothing about it before,” Castaneda said.

These young cuttings, which numbered about 350, would eventually replace the farm’s original section of citron trees, Kirkpatrick said. They were ones that had been planted by his father many years ago.

“This,” said Teichman, “is called an inflection point.”

Come summer 2026, these trees should provide Jews across the U.S. with etrogim for Sukkot.

The rabbi watched the laborers for a while longer. He was satisfied with their efforts. It was time for him to go. He approached Kirkpatrick, thought of the man’s father, and intoned a message: “May this year be a year of comfort.”

The workers paused in the shade of a sturdy valley oak tree. But only for a moment.

There were more cuttings to transfer. On this day — and the hundreds following it — Kirkpatrick and his colleagues would do all they could to secure a good harvest in three years’ time.

But, as farmers and rabbis have known for thousands of years, some things are beyond our control.

Kirkpatrick seems to have made peace with that.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.