- Share via

Anthony Farrer was running out of time.

He had built his luxury watch empire on a simple consignment model. Customers would bring his company, the Timepiece Gentleman, their watches. Farrer would sell them, online or from his Beverly Hills showroom, take a commission and give his clients the rest, which might total in the tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars.

The watches were flashy — diamond-studded Patek Philippes and Audemars Piguet pieces best kept in a safe — and so was Farrer, a Mercedes-driving semi-celebrity who rose in half a decade from a nobody with a criminal history to the top of the watch-dealing game by plastering himself and his exorbitantly upscale lifestyle all over social media.

But now his clients were getting restless. Several had noticed their watches had mysteriously disappeared from his company’s website. Yet they had not been notified of a sale, they told The Times.

They had questions, and when Farrer didn’t answer them, they went online. Quickly the same online community of watch aficionados that brought Farrer prominence turned against him, trading rumors about alleged misdeeds in a furious vortex of internet schadenfreude.

Farrer responded the only way he knew how, by posting a video online.

“The stuff I did was wrong. Spending people’s money, living above my means. … I’ve been digging myself this hole and it’s a five-million dollar hole,” he said in the Aug. 2 video. “About three million of that debt is to two big clients of mine. One who acted as an investor and I used his money to fund my lifestyle.”

Sitting in a tank top in a spare kitchen in front of dishes in the sink and an empty paper towel roll on the counter, Farrer monologued for nearly 15 minutes.

“This is a rock bottom for me. Feeling like this is worse than sitting in a prison cell, which is where I may end up. I don’t know.”

Farrer’s story is a cautionary tale full of contradictions. A gaudy lifestyle that belied growing money problems. A fall that unfolded in front of millions on TikTok, YouTube and Reddit — where two separate forums are dedicated to Farrer’s company’s alleged improprieties — while receiving no mention in the mainstream media. An alleged culprit who bounces between apology and denial.

Seven people told The Times they had given Farrer watches ranging in worth from $10,000 to well over $100,000 on consignment only for them to disappear, often without a trace. One of the seven has a pending lawsuit against Farrer over the issue; an eighth person who also sued did not speak with The Times.

Farrer has not been arrested or charged. Emails reviewed by The Times show the FBI and Beverly Hills Police Department are investigating the case.

Farrer agreed to be interviewed by The Times and spoke broadly about his work, background and money problems, though he sometimes declined to comment on specific allegations.

“I owe people money,” he said. “But ... no one ever brought me a watch and I immediately sold it and then pocketed that cash for personal use.”

Farrer, 35, says he grew up in Sherman, Texas, in an adopted family along with his twin brother and their biological sister. He said he lived a sheltered young life, not allowed to party or have sleepovers. He moved to Dallas at 18, searching for independence.

As Farrer tells it, he bounced between jobs but was always aspiring to afford a better life. At the same time, he fell into drugs and alcohol and spent his 20s drinking, getting in fights at bars and racking up DUIs.

He served time in prison in 2008 for running from cops on a motorcycle and again in 2016 for a DUI, he said. In prison in 2016, he missed his mother’s death and the birth of his son. When he got out, he decided it was time to shape up and get sober.

He owned a Breitling Chronomat watch and sold it when he came out of prison, bringing in $500 in profit, he said. It was the first watch he ever sold. Soon he was hooked. He quit his job as a waiter and slowly the money began to pour in.

Five lawsuits say FBI overstepped its powers by seizing contents of hundreds of safe deposit boxes

He founded the Timepiece Gentleman in Dallas with a partner in 2018, and the duo quickly gained a substantial following on social media as well as some legitimacy in the watch world.

“People trusted him in this space because he had a social media following,” said John Buckley, a luxury watch dealer who runs a business called Tuscany Rose.

Buckley said that Farrer had a talent for presenting an over-hyped narrative of his own success.

Farrer was a spectacle and he sold himself that way. In one video, he showed himself spending more than $17,000 at Salt Bae’s restaurant Nusr-Et to celebrate his birthday. He didn’t enjoy the meal (“That place sucks,” he said in an interview). But the video got a million views, so Farrer saw it as a success.

He said once that two types of people were interested in his content: haters and followers.

“One video can give both sides of the playing field enjoyment,” he said.

By early 2022, Farrer appeared to be cultivating a life at the very apex of American wealth. He moved to Los Angeles, where he saw people who were even wealthier than watch lovers in Dallas. His customers in Los Angeles would spend $100,000 without blinking, he said.

Farrer’s spending increased too. He leased a downtown L.A. penthouse in March 2022 — a rental that has been called the most expensive penthouse in the city at 825 South Hill St. — for about $100,000 per month, according to his former Realtor. Farrer hoped to relocate his watch business to the six-bedroom, 11-bathroom space, which featured commanding views of the Los Angeles skyline, a rock-climbing wall and three bars. Farrer planned to live there with two of his employees.

He started chronicling his glamorous lifestyle in 2022 with his own video series called “South Hill.” He posted the sleekly edited episodes on YouTube, another platform where he found an eager audience that engaged with his content and became potential future customers.

He also used social media to address scandals or problems as they came up. In March 2022, he addressed directly on his show rumors that he used to have a profile as an erotic masseur on a website that catered to gay men.

It was fodder for Farrer’s critics, who used it to mock him online. The revelation prompted his business partner in Dallas and another investor to sever ties with him, Farrer said.

“As a two-time ex-felon currently on parole, it’s very hard. It’s hard to get a job,” Farrer said on his YouTube show. “I did what I had to do to get what I wanted. … I don’t regret a day of my life.”

Farrer did not care what people thought of his past, he said. The money was what mattered. But there were problems there too.

Like other collectibles, the luxury watch market soared during the COVID-19 pandemic. Wealthy buyers felt shut in and had money to spare, said Ariel Adams, a journalist who runs aBlogToWatch.

A Rolex Submariner on the resale market that sold for, on average, about $13,000 in the fall of 2018 could fetch nearly double that by March 2022, according to WatchCharts. As prices rose, some started to view watches as a “quasi-investment” despite the risk of volatility, Adams said.

The watch market peaked in March 2022 and has been trending downward since, though average resale prices still hover higher than they were in early 2021, according to WatchCharts.com.

Farrer’s business was thriving as the market reached its peak, but he was caught holding the bag when it cooled back down, he said. The inventory of watches he possessed — he claimed $3 million in value — was depreciating every day, he said. Nobody wanted to buy.

“Almost overnight, prices dropped 20%,” said Farrer, but he did not adjust his spending accordingly. “I was still living lavishly, still going out and buying cars.”

Just three months after he had leased the penthouse, Farrer moved out, his Realtor said. He had spent $500,000 on deposits and rent, plus another $600,000 on furniture, landscaping and security systems, Farrer said.

Working with a consignment dealer requires patience. Items don’t always sell immediately; sometimes they don’t sell at all.

But by the summer of 2023, some clients were growing concerned when they noticed the listings of their watches no longer appeared on the Timepiece Gentleman website without any notice about a sale.

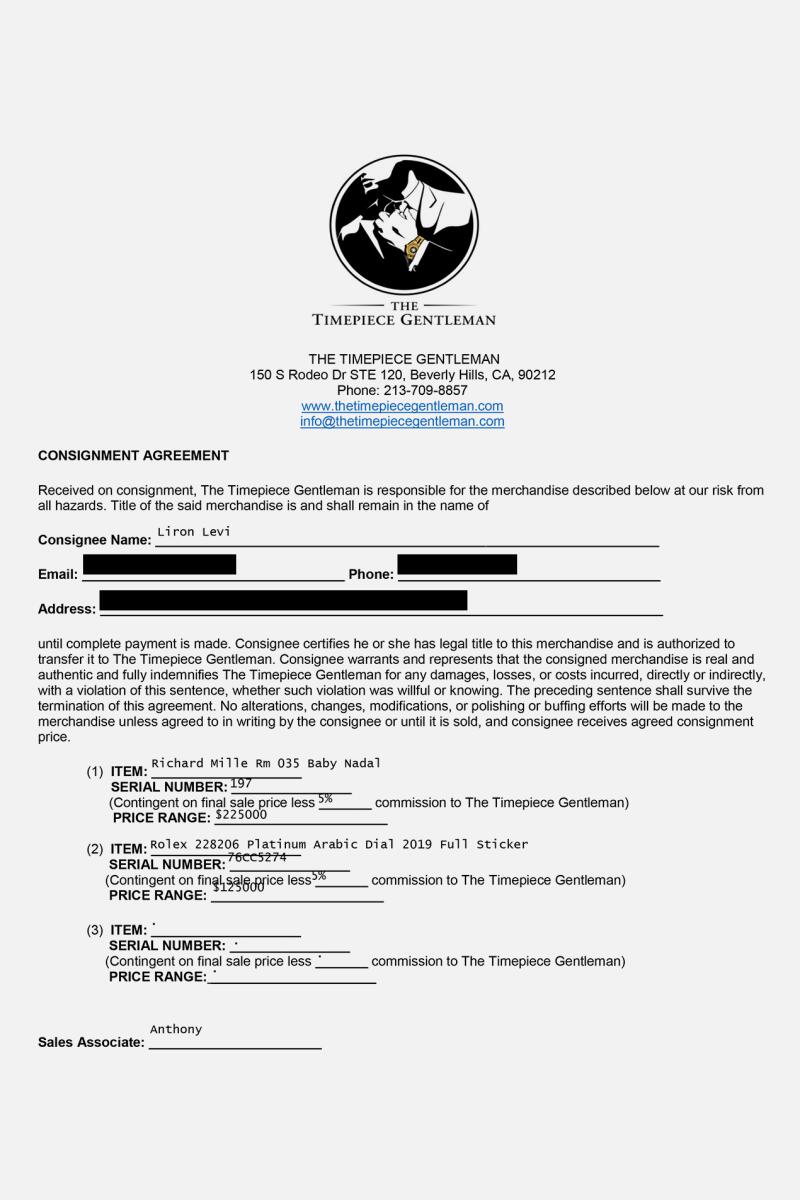

According to four consignment agreements reviewed by The Times, clients agreed to give their watches to the company for a minimum of 30 days. If a sale went through, Farrer was to take 5% and deliver the rest of the money to the consignee within one business day of receiving payment from a buyer.

1

2

1. (Consignment agreement courtesy of Liron Levi - page 1) 2. (Consignment agreement courtesy of Liron Levi, page 2)

One client, Artin Massihi, filed suit in Los Angeles County Superior Court claiming that Farrer stole his Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Offshore 44mm worth at least $40,000. He had given the watch to Farrer on July 5 under a consignment agreement reviewed by The Times.

Weeks later, according to the lawsuit, Farrer admitted to Massihi on the phone that he “sold the watch and kept the entire funds for his own [personal] purposes.” Farrer promised to pay him back in weekly $3,400 installments. After the first payment, no more came, according to the suit.

“I told him I don’t have any more money,” Farrer told The Times. “I stayed in contact with him and I said, ‘Look, I’m doing my best. I’m working.’”

Bob Schober, a retired 50-year-old who likes fancy watches, was having trouble with Farrer too.

After coming across the Timepiece Gentleman’s TikTok account in February, he said he bought a Rolex Sky-Dweller and a Patek Phillipe from Farrer and everything went smoothly.

“He was selling real watches. He sells to famous sports stars,” Schober said. “Anytime I bought a watch from him I’d bring it to a local dealer and say, ‘Is this legit?’ They were never knock-offs.”

Schober trusted Farrer enough that he let him stay in the guest room of his house in Arizona in May.

“I liked the guy,” he said.

In July, he gave Farrer two watches to sell. Schober said they did not sign a consignment agreement because they were friends. Soon after, Schober heard from a friend that Farrer owed a lot of people money.

Schober checked the Timepiece Gentleman’s website and realized the watches he had given Farrer were no longer listed for sale — yet Schober had not received payment or been informed of a sale, he said.

When the two got on the phone to discuss it, Schober recorded the conversation and posted videos to his TikTok. In the recording, Farrer says he has a debt of $5 million and that he would “rob Peter to pay Paul.”

The videos caught fire among among Farrer’s online fans and foes. As the clips racked up millions of views, Schober said dozens of people messaged him saying Farrer had taken their watches and never paid them.

TikTok watch enthusiasts traded stories about Farrer in the comments. Others took to their YouTube channels. Two separate subreddits — one with more than 500 members and another with more than 5,000 — focused on Farrer. Stories, rumors and memes swirled about the Timepiece Gentleman.

“It blows my mind that people spend that much time focusing on someone like me, versus going and doing anything, like a hobby or a job or learning a skill,” Farrer said in an interview.

L.A. couple facing prison for stealing $18 million in a pandemic relief scam took a private jet to the Balkans and vanished into a posh town on the Mediterranean.

On July 27, Farrer shipped a different watch to Schober — a Rolex Sea-Dweller — to try to start paying back what he owed.

“Work with me at least on getting you paid back,” Farrer said in a text reviewed by The Times.

But Schober was concerned that the Sea-Dweller belonged to someone else, he said. When he received the watch, he immediately posted it to his TikTok.

“If you have lost a Sea-Dweller and you can prove it to me and you have the serial number and all of the history of your texts with [Farrer], then I’m happy to send this watch back to you,” he said in an Aug. 3 video.

Frank Lucente had been dealing with similar issues. He consigned his Rolex Sea-Dweller to the Timepiece Gentleman on July 12, according to a consignment agreement.

Employees at the Timepiece Gentleman told him that it would be a quick sell, Lucente said. So he became worried when his watch disappeared from the website without notice, he said. Farrer stopped responding to Lucente’s increasingly frantic texts about the watch, according to messages reviewed by The Times.

Lucente saw things popping up on the internet about Farrer owing millions of dollars to clients, then stumbled across a TikTok video from Schober offering to return the Sea-Dweller to its rightful owner.

The two messaged, and Lucente shared the watch’s unique serial number. Farrer had sent Lucente’s watch to Schober, the two agreed. Schober overnight mailed the watch back to Lucente in San Diego.

“It’s pretty incredible,” Lucente said. “I’m probably the only one that has or will get anything back out of this guy.”

Farrer denied selling people’s watches on consignment and keeping the profits for personal use. He declined to comment on Schober‘s and Lucente’s specific allegations. When asked if he ever used the proceeds of selling one person’s property to pay back someone else, Farrer said yes.

He also said that doing so “temporarily” prevented him from being able to compensate the person whose watch he had sold.

Farrer closed up shop in Beverly Hills in late August, according to someone who works in the building. On Aug. 2, he posted the 14-minute video to his YouTube acknowledging his debts. He also noted that a text he had sent to people to whom he owed money included lies about watches being stolen.

“It’s gotten to where living this fake lifestyle, living this ‘Look at me, I’m smart, I’m successful,’ keeping up the appearances, it’s eating me alive,” he said in the video. “It was all keeping up this facade. … I’ll admit it, I got a little taste of success and never wanted to forget that feeling.”

Later that month, he deactivated his social media accounts.

People who had given him watches and not gotten them back reached out to police and the FBI.

“This guy deserves to be prosecuted to the highest level due to the trauma he has caused our numerous victims,” Beverly Hills Det. Alex Kalé wrote in an email on Sept. 5 to Chad Plebo, a watch aficionado who helped connect authorities with alleged victims.

Kalé said that the FBI had taken over the case, according to the email.

The FBI declined to comment.

For those stuck in limbo, what they’re missing can be more than just a collectible.

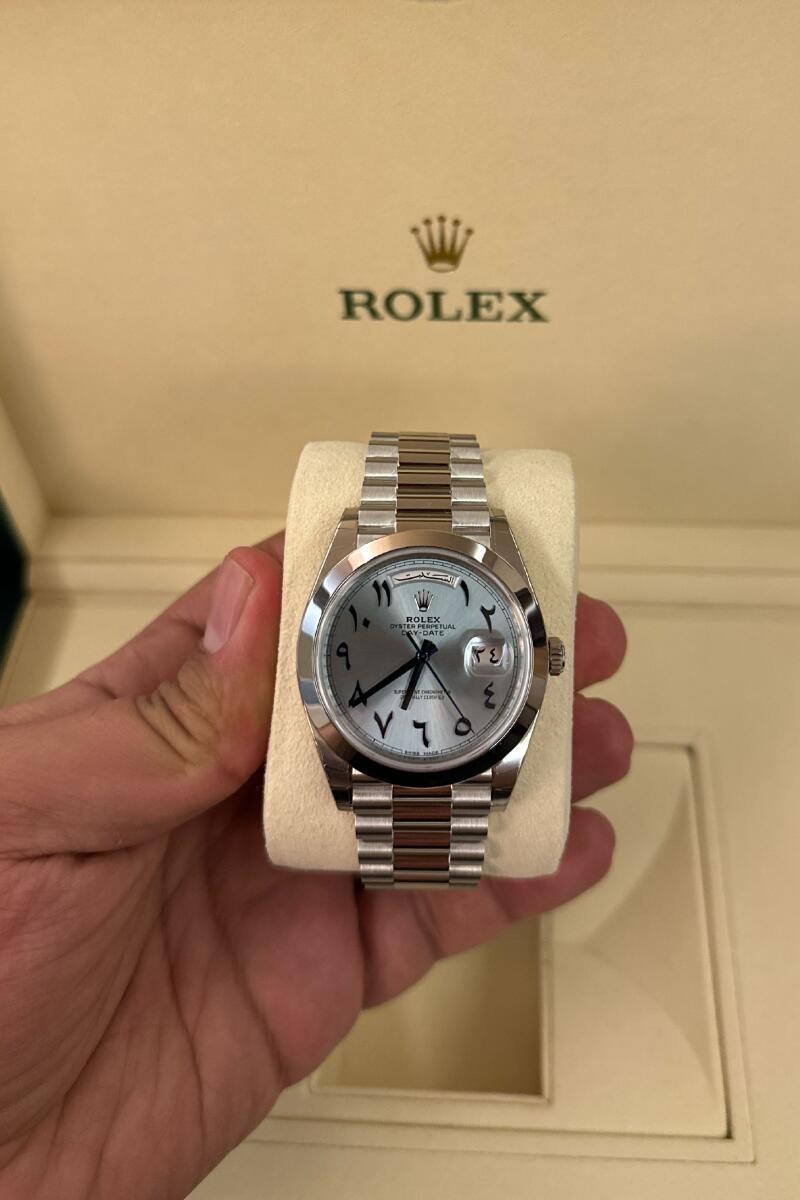

Liron Levi, 33, a locksmith who moved with his wife to Los Angeles from Israel last year, had invested their life savings in a Rolex and a Richard Mille worth about $350,000 total.

He decided to sell them in July so that he and his pregnant wife could make a down payment on a home. He went to four watch stores in Los Angeles, including Farrer’s, he said.

1

2

1. Liron Levi holding a Rolex Platinum Arabic Dial. 2. Liron Levi holding a Richard Mille Baby Nadal. (Liron Levi)

“Anthony was the only guy that really showed me confidence. ... He is a really good salesperson,” Levi said.

Levi signed a consignment agreement and gave the watches to Farrer, he said. He never saw them again — aside from a listing on a New York watch store’s website for the Rolex, same serial number and all. Farrer acknowledged to Levi that he no longer had the watches in his possession.

“I will get your watches back. I need a day. I’m going thru a huge financial disaster but I will get your watches back,” Farrer said in a text to Levi reviewed by The Times.

Months later, Levi is still missing his investment. His wife miscarried. He spoke with the police and the FBI. He said he has struggled to afford a lawyer to sue Farrer.

“I lost all my savings,” he said.

Farrer declined to comment on Levi’s watches.

Others have stayed in contact with Farrer even as he has gone mostly dark.

Mark Cardegnio Jr. said he consigned his Rolex Submariner with 18-karat yellow gold and diamond hour markers to Farrer in May. Cardegnio, a 28-year-old from Chicago, believed the watch to be worth around $30,000 in good condition, though he first gave it to Farrer’s company to fix up before selling.

When news of Farrer’s scandal began to break online, Cardegnio texted Farrer to see if his watch was still with the Timepiece Gentleman.

“Do you still have it in inventory?” Cardegnio asked in an Aug. 2 text reviewed by The Times.

“Unfortunately I don’t, man,” Farrer responded. “I meant when I said of my Youtube about realizing I f—ked up but I’m not going to run from it and while it may take me a little time I’m going to make everybody whole.”

“My heart sank,” Cardegnio said. “That was a pretty large chunk of change.”

Cardegnio said he stayed in contact with Farrer and tried to avoid being confrontational so that he could maintain a connection.

Farrer let him know on Aug. 20 he was leaving the watch industry and focusing on something else: heavy machinery.

“The opportunity looks very promising, but it’s gonna take a lot of work on my part but I’m ready for it. The other reason for this text is to mention that, while I have every intention of paying all of my debts back, right now I need to focus on getting some money coming in and I think it’s gonna take at least a month to start seeing that happen,” Farrer wrote in a text.

Farrer said he continues to sell watches on the side and also is working as social media consultant. While speaking with The Times, Farrer even got a compliment from a stranger on the red-and-blue Rolex he was wearing — those in the know call it a Pespi GMT. The watch belonged to a friend, he said.

“I’m taking it to sell to somebody tomorrow,” Farrer added.

Farrer texted Cardegnio on Sept. 20 offering social media consulting and marketing help as a way to start paying back the money he owed.

He also was upset that one of his “debtors” was sharing screenshots of his messages.

“Not sure why someone I owe money wants to continue to jeapordize [sic] my ability to pay you back but when I confirm they will be moved to the bottom of the list,” he wrote.

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.