For some people, retirement is a long-awaited chance to sleep late, relax and celebrate the joys of life without pressure or deadlines.

For others, it’s an opportunity to finally get to work.

California is about to be hit by an aging population wave, and Steve Lopez is riding it. His column focuses on the blessings and burdens of advancing age — and how some folks are challenging the stigma associated with older adults.

Within a span of a few days, I heard about two retirees who had long dreamed of becoming authors, but their jobs kept getting in the way. Then they pulled the cord, hit the keyboard and never looked back.

I was on the phone one day with former L.A. Times columnist and editor Bill Boyarsky, and when I asked about his wife, Nancy, he gloated. Her seventh novel had just been published, he said, and she was already working on her eighth.

Then I heard from L.A. County Superior Court Judge Kelvin Filer, who was talking up his brother, Duane. “He actually wrote a book documenting his first year of retirement,” the judge said. Before he excused himself with “I have to get back to my murder trial,” he added that his brother has since written several other books.

I hear fairly often from people who use retirement to chase dreams. Some set out to learn an instrument or a new language or two. Others turn volunteering into second careers. But I probably hear from more aspiring writers than any other group of people setting out to reinvent themselves.

So I paid visits first to Nancy Boyarsky, 87, who lives in West L.A., and then to Duane Lance Filer, 71, who lives in Carson.

Boyarsky toils in a back room drenched in natural light, her cat Roxy at her side. She was a reader as a child and a fan of Jane Austen. At UC Berkeley, she took a creative writing class, “but the teacher didn’t think much of my short stories.” She recalls “a condescending smile” and a stabbing suggestion that the writing life was not for her.

And yet she went on to make a living at a typewriter, banging out articles for various publications including the L.A. Times magazine, and she was an editor for a magazine called “L.A. Lawyer. She co-authored a book called “Backroom Politics” with Bill and spent the last 18 years of her career as ARCO’s director of communications for political affairs.

While still at ARCO, Boyarsky took some writing courses at UCLA and began working on a novel called “The Swap.” The protagonist is a Los Angeles housewife who discovers on a trip to England that her husband is a cheat and that her life is in danger, a realization that transforms the “browbeaten housewife” into an enterprising private detective.

But when Boyarsky retired in 1998, she discovered, as so many writers have, that getting a book published is a tough racket, with your odds of success roughly similar to your chance of winning the Powerball lottery.

“I got an agent, and he sent it out to publishers, and they rejected it,” Boyarsky said.

A freelance editor suggested a major rewrite. Boyarsky did not agree, and she kept pursuing agents and publishers without success before putting the dream in a drawer and taking up painting. Her house is filled with her work, including impressive portraits and botanical art.

But Boyarsky hadn’t entirely given up. In 2013, she took advantage of a growing trend and self-published on Amazon.

“Mary Higgins Clark meets London … ’The Swap’ contributes to the women-driven mystery field with panache,” one magazine critic raved.

“I was thrilled,” Boyarsky said, and the news got better.

A small North Carolina publishing house called Light Messages reached out to say it wanted to re-publish “The Swap,” and Boyarsky was asked if she could turn her heroine into a serial sleuth. Seven Nicole Graves mysteries are now in print, and Boyarsky is hammering out the eighth while Bill, also a prolific author, works in another room on his next book.

Light Messages edits, designs, distributes and markets the Nicole Graves books on a small budget, with Boyarsky getting a percentage of sales. (“The Swap” has more than 2,000 customer reviews and a four-star rating on Amazon.) Boyarsky said she made several thousand dollars on that one, less on the others, and she wouldn’t advise book-writing for anyone looking to get rich.

But clearly, that Berkeley professor was clueless, and Boyarsky keeps writing — for love, if not for money.

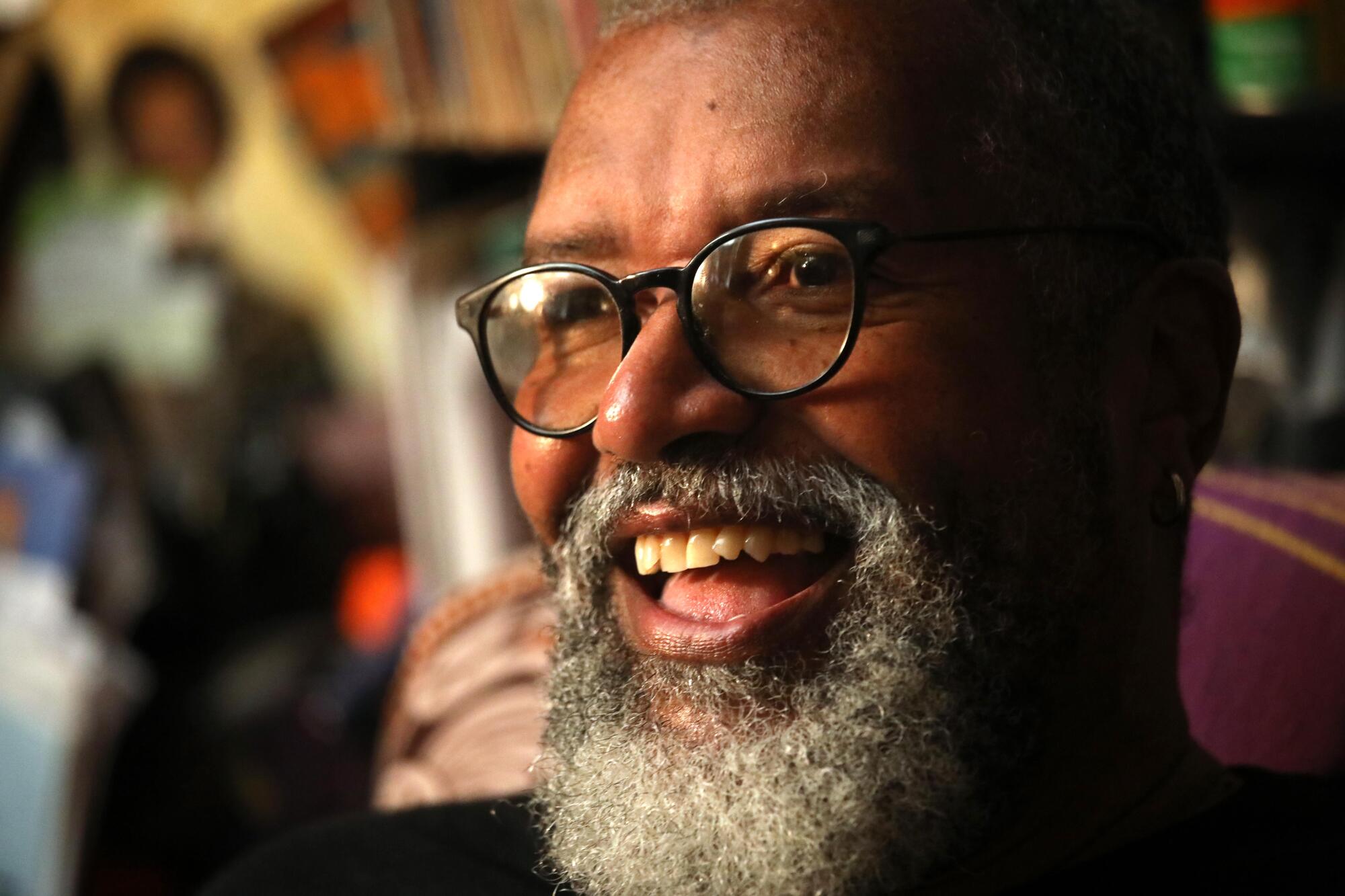

Duane Lance Filer had a bit of a different start. Rather than being told the writing game wasn’t for him, he got nothing but encouragement from his Black history teacher at Compton High School.

“Mr. Taylor,” Filer said. “Alvin Taylor. He said, ‘Pursue your dreams.’”

With that, and inspiration from the civil rights activism of his parents — Maxcy and Blondell Filer— Filer majored in political science at Cal Lutheran and wrote short stories there, joining the Watts Writers Workshop after college. Like a majority of aspiring writers, Filer had a day job, and for the last 29 years of his working life he was in the consumer affairs division of the California Public Utilities Commission, handling customer complaints.

Toward the end of that career he wrote his first book, a semi-autobiographical novel about an aspiring young Black writer growing up in a changing Compton, a witness to white flight during the civil rights movement. Then, after retiring in 2013, he spent a year writing a breezy book called “The Baby Boomers First-Hand, First-Year Guide to Retirement.”

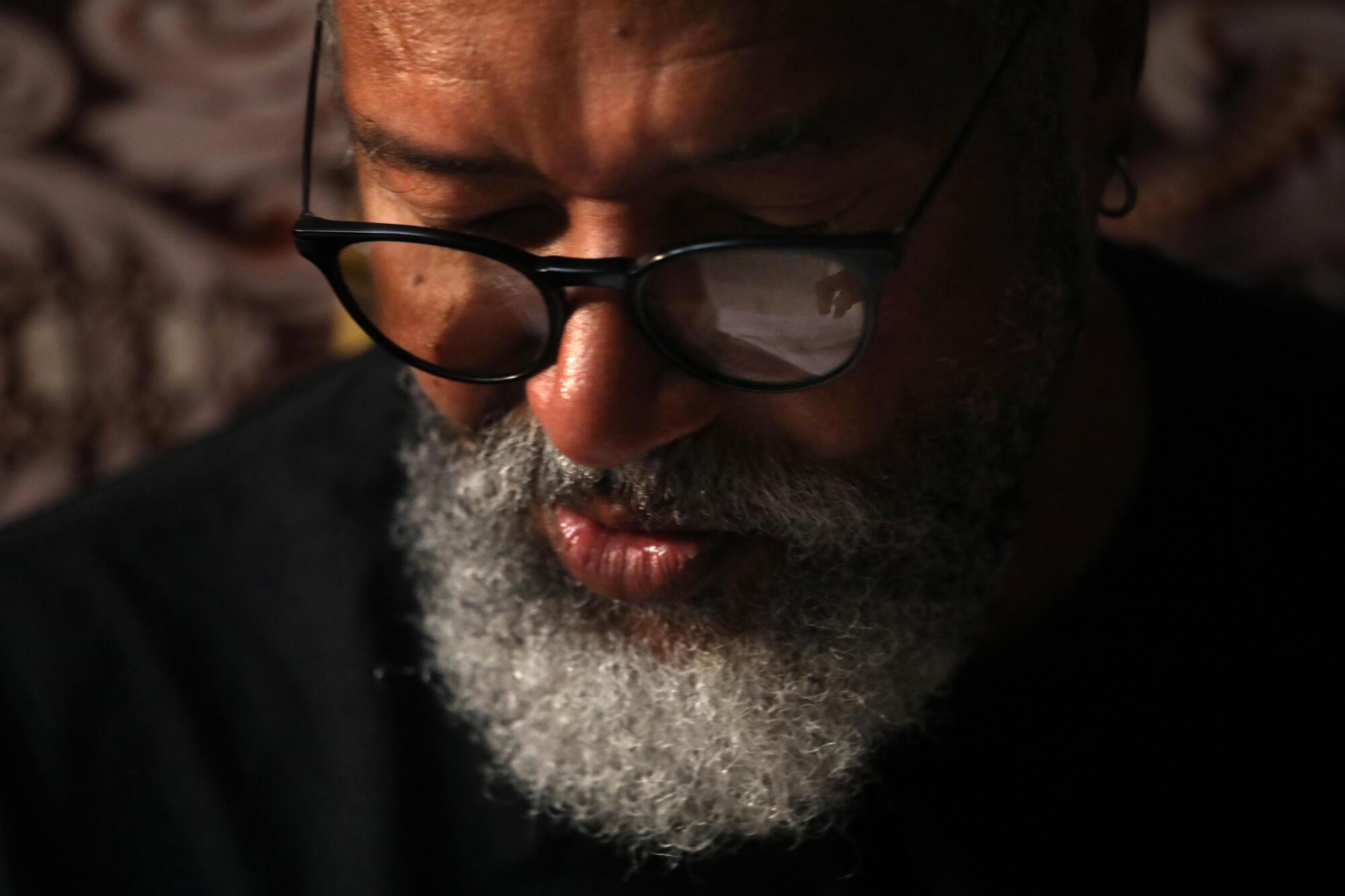

Filer didn’t miss the train rides to and from work. There was lots of vacuuming and cleaning to be done, and he often shopped and prepared dinner for his wife, who was still working. There were some ups and some downs, but no regrets about retiring. On Day 365, Filer entered his writing den — he calls it the fffunklab; the three Fs stand for “Filer Family Fun”—to pen the final words of his guide while listening to Etta James sing “At Last.”

The fffunk lab, by the way, is where I visited Filer. He’s carved out the space in a corner of the garage, with images of Miles Davis, Jimi Hendrix and Sly and the Family Stone surrounding him. He wore faded, patched jeans and a George Clinton Funkadelic T-shirt, calling himself an unreformed hippie. In a family of lawyers and educators — son Lance is an attorney, daughter Arinn is an assistant principal, wife Janice is a professor and retired principal — Filer is all about music (he plays bass guitar), art (he paints), and words.

The fffunk lab is a supremely cluttered cave of sports and family memorabilia, along with the tributes to his favorite musicians. The desktop computer, on which the funkmaster has now written nine books, sits in one corner. He’s penned several children’s books and a novella called “The Legend of Diddley Squatt,” loosely inspired by the life of the late comedian Richard Pryor, who grew up in a brothel. Filer is now working on a sequel, his 10th book, and a screenplay about his father’s life.

The only fly in the punch bowl is that despite his dogged efforts, Filer has no agent and no traditional publisher. He has self-published, paying different companies to print and distribute his books, hoping to recover the investment through sales.

“I usually send out between 50 and 100 query letters with each book,” Filer said.

The lack of response has not deterred him one iota. He sat in on some writing classes at nearby Cal State Dominguez Hills several years ago and keeps the dream alive, noting that his father took the state bar exam over and over again — literally dozens of times — before finally passing.

Perseverance, he tells himself. Perseverance.

He takes his morning walk while listening to his favorite music, reaching deep for inspiration. Then he enters the fffunklab, subjecting himself to the joys and cruelties of creative endeavor.

“I love to write, and here’s the thing: None of my books make any money, or, I haven’t made a lot of money,” Filer said. “But I don’t care. At some point, my little grandson can say, ‘Oh, you never gave up.’ I will never stop writing. … I think this next book is going to be my best one.”

steve.lopez@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.