The yelling surprised no one. Yet still Craigen Armstrong was concerned.

Ray was always acting out. This time he had just come back from medical and was standing at the glass wall, screaming at the sheriff’s deputies on the other side. He was furious, accusing one of them of sleeping with his wife.

Armstrong and the other inmates in the cell block hoped the disruption would blow over. But Ray only got louder and more frustrated.

“He had severe delusions,” Armstrong said as he recalled the incident.

Deputies began to muster. They had tried to talk to Ray and would typically intervene with a psychiatric clinician — per protocol — but the situation was getting worse fast. With no other option, they issued their command.

“Take it in!” they yelled. “Everyone, take it in!”

The inmates in the block tensed.

Seated in the chairs and sofas of the dayroom for morning karaoke, they stood, filed to their cells and closed the doors, but Armstrong held back. Twelve years on San Quentin’s death row had taught him how easily old traumas are awakened by new assaults. He worried about Ray, who lived with symptoms of schizophrenia.

Armstrong knew he risked a reprimand for not following orders. At any moment, the deputies would storm the unit. He knew they saw Ray as an unresponsive inmate, but he saw a patient in distress.

He feared that Ray would fight back. His fists were clenched.

“Hey, Ray, I want you to come in here,” Armstrong said, encouraging the inmate to return to his cell. “I want you to be safe.”

If there were a fight, someone would likely get hurt, and all that he had worked so hard to get — the DVD player, monitor, plants, snacks, toiletries — could get trashed in the struggle.

“I want you to be safe,” Armstrong repeated and explained that the deputy didn’t know his wife, had been on shift all morning, hadn’t even left the floor.

Armstrong saw custody staff taking up their shields. Ray kept screaming. They were about to move. Pepper spray would be used, a Taser the last resort. Armstrong stepped closer and reached out and touched Ray.

The two men locked eyes, and like a flipped switch, Ray fell silent. His expression went slack, and as if nothing had happened, he returned to his cell. Armstrong made sure his door was secure.

Rules are often bent on the fourth floor of Twin Towers Correctional Facility, where many inmates are like Ray — volatile and frightened, the worst symptoms of their mental illnesses kept in check by a balance of medication and monitoring.

When Armstrong first heard about working here, it sounded like a good deal: passing out meals and snacks, helping with meds and hygiene, keeping cells and common areas clean, all in exchange for his own cell and a few extra privileges.

Armstrong had returned to Los Angeles from San Quentin months earlier after unexpectedly winning his appeal in 2016. The state Supreme Court had tossed out his conviction of murdering three brothers in Inglewood in 2001. Still facing the charges, he remained in custody while his attorney and the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office discussed a plea deal or another trial.

He had initially been housed in the nearby Men’s Central Jail, but the politics — the often violent racial divisions — kept him on edge. Living and working among the inmates in Twin Towers, the jail’s de facto mental hospital just across the street, gave him an out.

There were times when he wanted to give up. He knew little about mental illness, how erratic moods govern behavior, how anger or fear leads to violence or withdrawal. He heard the men crying at night. He saw how they tried to hurt themselves, sometimes succeeding.

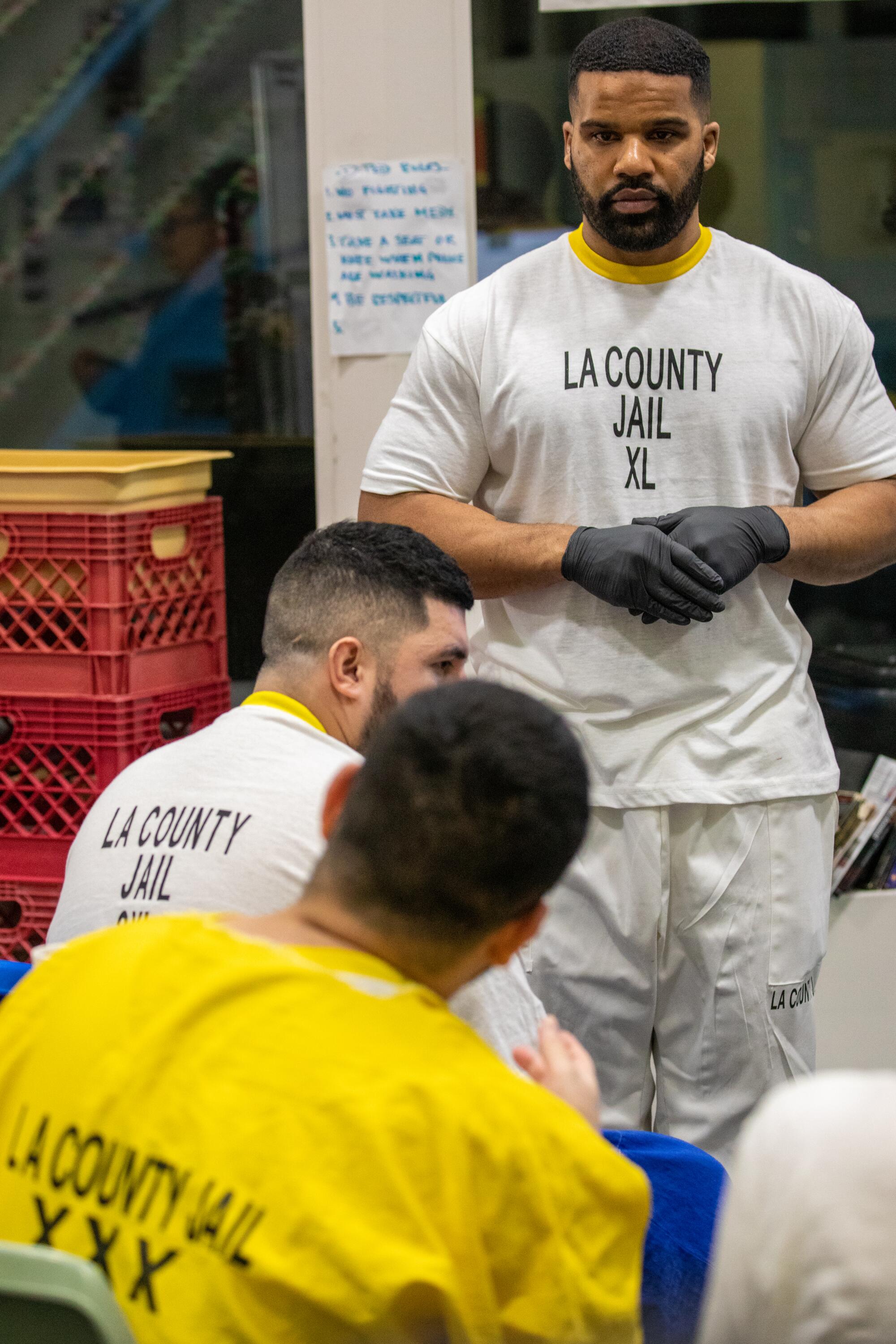

But partnering with another inmate, Adrian Berumen, Armstrong, 42, grew adept at interacting with the inmates, whom he came to see as patients. Over the last six years, he and Berumen, 28, who left Twin Towers in 2022 to serve a sentence in state prison, engineered a transformation inside the county jail system.

Twin Towers Correctional Facility is a fortress on the edge of downtown L.A. Behind its walls, a small group of inmates is working to help those with mental illness manage their symptoms and the rigors of incarceration.

The idea — initially developed by the county Department of Health Services, which is responsible for providing healthcare in the jails — was based on peer counseling programs and brought inmates from the general population into the jail’s psychiatric units, where they would live and assist county staff with treatment services.

The program had been in place, but the results were inconsistent until Armstrong and Berumen arrived. They studied and collaborated. They recruited and trained other inmates, put together a six-month educational curriculum and started calling themselves mental health assistants. They wrote a book and were invited to speak to students at Stanford and Cornell universities and to members of the National Assn. for Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement.

Their accomplishment is especially noteworthy given the Sheriff’s Department’s troubled management of its jail facilities, where in 2021, 12 inmates died by suicide, four of whom were housed in Twin Towers.

The jail facility houses a little more than 2,200 inmates, more than half of whom have been diagnosed with severe mental illness, according to a spokesperson for the Sheriff’s Department. These are arguably the most vulnerable to suicide, and while the department has struggled to keep these men safe, Armstrong and Berumen have shown what is possible.

“I don’t think anyone could have foreseen how successful their work would be,” said Joan Hubbell, who manages the mental health programs throughout the jails for the Department of Health Services.

While the sheriff’s deputies were initially skeptical that Armstrong and Berumen’s work could be successful, the department now sees the importance of their program.

“Lord knows,” said Sheriff Robert Luna at an event at the jail in October, “when we talk about custody, the stories aren’t always the most positive. ... [But] I’m really impressed with the innovation of the program and the impact that it has on our incarcerated community who suffer from mental illness.”

The county Board of Supervisors has also added its endorsement.

“I do believe this is a vital program,” Supervisor Hilda Solis said during a June board meeting. “I think ... this type of assistance is so critically important. It will save lives. It will save costs.”

Solis’ judgment came after visiting the jail and witnessing “the incredible and difficult work” that Armstrong and the other assistants do. In championing the program, she invited Armstrong and two other inmates to speak to her colleagues by video call and credited them for an achievement she considers “amazing.”

Afterward, the supervisors voted unanimously to expand the program from about 100 to more than 600 patients by 2025 in both Twin Towers and the Century Regional Detention Facility for women. The cost of this expansion is estimated at $850,000.

The supervisors’ decision was “a very crystallizing moment,” Armstrong said on the phone afterward. He and Berumen knew that the program could help more inmates. Now they had validation.

However, as Armstrong works to meet the supervisors’ mandate, he wonders if he’ll see it finished.

Lying in his bunk at night — a 2-inch-thick mattress and a pillow made of a blanket folded inside a T-shirt — Armstrong puzzles over his life: how the most unlikely place — jail and prison — opened his heart.

When he thinks about how it began, he reflects on where it might have ended: strapped to a table with IV lines running into each arm.

No one denies the magnitude of the tragedy that took place over two nights in 2001 when three brothers — Christopher, Michael and Torry Florence — were slain on the streets of Inglewood. The details came out in a well-publicized trial three years later.

Christopher, 21, was shot driving down a street claimed by the Crenshaw Mafia Gangsters. Michael and Torry, 27 and 29, were killed in a shooting two nights later trying to get information about Christopher’s death.

Armstrong was arrested and charged with murdering the three men.

Jurors listened to testimony from 38 witnesses and reviewed 130 pieces of evidence. Testifying on his own behalf, Armstrong denied involvement in Christopher Florence’s death and claimed he shot the others in self-defense. He expressed “remorse and regret” that the brothers had died.

He hoped for a hung jury, and he almost got one until the judge replaced a juror for failing to deliberate and another for failing to disclose a friendship with one of Armstrong’s relatives.

Conviction followed.

During the penalty phase of the trial, jurors learned of Armstrong’s criminal past, which included robbery, witness intimidation, assault and attempted murder, and they also heard testimony about his childhood, the events that led to his family breaking up and a local gang filling in the void.

They heard from Brenda Florence as well. The mother of the three brothers described the intensity of her grief as if she had been “dropped in the pits of hell,” and on Sept. 24, 2004, the jury sentenced Armstrong to death.

He soon found himself shackled in a cage in a bus with a half-dozen other inmates leaving Los Angeles for San Quentin.

On death row, Armstrong’s cell was so narrow he could stand in the middle, stretch out his arms and touch the walls. He looked across at windows so opaque they barely let in light and catwalks where armed guards walked cradling assault rifles.

He was alone, 23, with the courtroom voices echoing in his head saying he deserved to die. Not long after he arrived, two inmates were executed.

“There is no light at the end of the tunnel,” he said. “You think that this is what it will be like until you die.”

One day Armstrong bought some marijuana and meth. He said that he intended to sell it, but instead smoked it himself and got so high that for a moment, as he recalled, nothing else mattered.

But he was too young to give in to despair, he said. The first book he read in prison was Dale Carnegie’s “How to Win Friends and Influence People,” and he started to listen to older inmates — Barry Williams, Albert Jones — whose advice was clear. Remain steadfast. Stay positive. Turn away from drugs. Watch whom you associate with. Learn something. Keep your mind strong.

In 2009, he caught a glimmer of hope when he met Patricia Scott, an attorney who was handling his appeal.

She had been appointed through the California Appellate Project, an initiative of the state Supreme Court started in the early 1980s as an attempt to guarantee effective representation for condemned defendants.

Armstrong was her first capital case. She remembers a young man with neatly braided long hair, wearing blue pants, blue shirt, waiting for her in the attorney-client visitor center.

He impressed her with his ambition, intending to get an AA degree in business through online community college classes. He wanted eventually to get a bachelor’s degree in sociology.

Scott pored over 5,300 pages of trial documents, searching for any errors committed by the judge or the attorneys.

What puzzled her most were the jury deliberations, carefully rendered in the court records.

Two days after closing arguments, the foreperson sent a note to the judge saying the jury was deadlocked. The judge called it an “absolute travesty” that the trial might end so soon. He told them to keep at it.

Later that afternoon, the jury sent more notes. One said that juror No. 12 knew Armstrong’s cousin. Another claimed that juror No. 5 “refused to listen to the other jurors. … She either does something on her cell phone or reads her book.”

The judge excused the two jurors. Alternates took their place, and three days later, the jury returned with a unanimous verdict.

San Quentin schedules two mail deliveries a day. The first cart carries letters from family and friends; the second cart, mail from lawyers and the courts. When Armstrong saw the second stop in front of his cell in August 2016, he knew the wait was over.

Two months earlier, Scott had argued his case before the seven state justices, and he knew their opinion was due any day.

He expected a rubber-stamp denial, leaving him to appeal to a federal court. He was 35 and had been incarcerated for 15 years.

He tore open the legal-size envelope.

“The judgment is reversed in its entirety,” the chief justice wrote.

He did not believe it.

The justices agreed that the removal of juror No. 5 was unfounded and had prejudiced the outcome of the case. The unanimous decision was exceedingly rare. According to the California Appellate Project, since 2003 the court has overturned 12 out of approximately 430 murder convictions.

But he wasn’t free. “Retrial of the case is not barred by the double jeopardy clauses of the state and federal Constitutions,” the ruling said.

Two months later, Armstrong was in a prison bus, shifting his gaze to a world that he hadn’t seen in 12 years. The bus took the 101 Freeway south and slowed in L.A. night traffic. Dodger Stadium was lit up; postseason had begun.

Once back at Men’s Central Jail, he started to take classes, but accustomed to his own cell on death row, he found it hard navigating around the politics of the general inmate population.

When he heard of the job in Twin Towers, he decided to apply.

Twin Towers opened in 1997 as a holding facility for men and women charged with misdemeanors and felonies and awaiting trial. But it soon became known as “the largest mental institution in the country,” a surge driven by the region’s worsening homelessness and behavioral health crisis.

Built for a general population, the jail was designed to keep deputies and inmates apart, a disadvantage for those with mental illness who need regular monitoring and safety checks.

Armstrong was assigned to the fourth floor, which had been set aside for inmates who agreed to take medication, were referred by clinicians and were considered to be safe around others. The unit is known as Forensic Inpatient Stepdown, or FIP Stepdown.

Soon after settling in, Armstrong met Berumen, who had come over from Men’s Central a few months earlier and, like Armstrong, was at first somewhat lost.

“I never, not once, knew anything about schizophrenia or the severity of bipolar where someone can be happy and loving and then hating you and wanting to kill you,” Berumen said in a call from Calipatria State Prison, where he is serving 25 years to life for the murder of Christopher Waters, a 42-year-old artist from Long Beach.

The job was to assist a life skills teacher. Berumen described the work as little more than being an aide, but when funding was cut and the teacher stopped showing up, Beruman and Armstrong thought they should keep it going. They were soon overwhelmed.

“I knew nothing about my feelings,” Berumen said. “I was raised not to think about them, so I never knew how to empathize or communicate what I felt.”

Armstrong understood what held them back. “This is a system that disincentivizes empathy,” he said. “In jail, we’re thinking about ourselves in order to survive. So it is hard to think about others.”

The two inmates found an ally in Sarah Tong, a psychiatric technician on the floor, one of approximately 200 mental health clinicians that the Department of Health Services employs to oversee patient care in the jail.

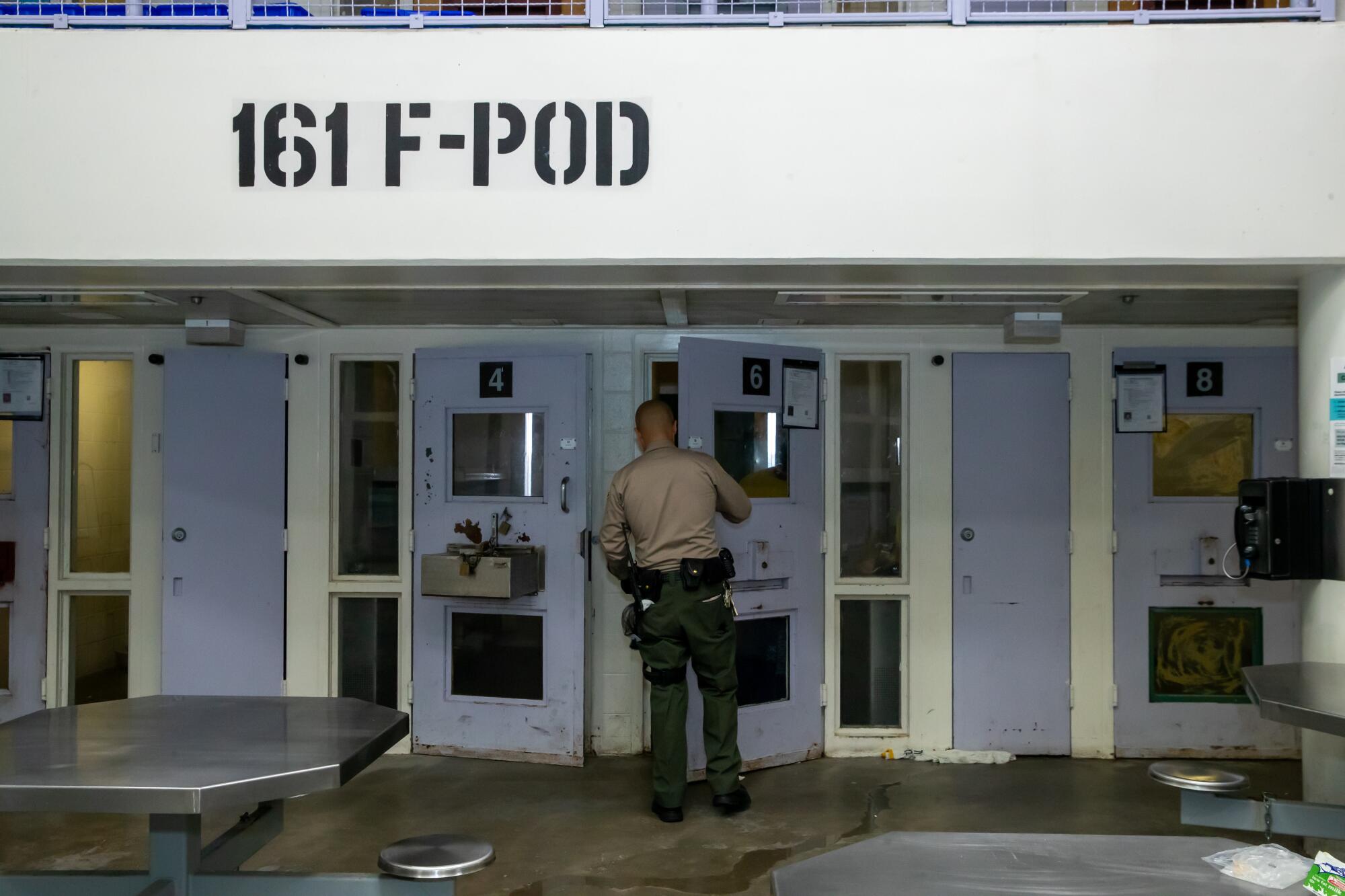

Tong started in Twin Towers in 2005 and first conceived of the idea of setting aside a “pod” — a unit of housing for 32 inmates — for patients who were stable but needed help and encouragement managing their illnesses.

She structured each week with art therapy, karaoke, games and group discussions about substance abuse and courtroom etiquette, but she was working outside the pods, leaving patients alone for hours.

Inmates from Men’s Central could help, but the first hires were uncertain what to do. Armstrong and Berumen were different.

“They were very driven and smart. They really focused on how they could expand this program,” said Tong, who taught them about mental illness.

The two men began to call the men they helped “patients” — not “inmates” — shifting the focus to their recovery.

They developed an incentive system so that cleaning cells, showering, brushing teeth, taking medications and participating in group discussions would mean an extra snack or more time outside a cell.

“What slowly fell in place was the inmates’ humanity,” Tong said. “No longer were they to be feared and shunned, and no longer did they fear and shun. They began to understand that not everyone in this environment was there to hurt them, that maybe they could try something good.”

As inmates became more stable, deputies also found their work less stressful, and as much as Armstrong, Berumen and the other assistants strove to humanize the patients, they realized they were humanizing themselves in a system that had seemed intent upon depriving them of it.

Armstrong’s cell — No. 10 — is slightly larger than the one on death row. During the day, a dull light leaks through the cloudy glass of a 3-inch-wide by 3-foot-tall window.

On one wall, he has taped a small print of a cloud of interstellar dust sparkled with stars, some 7,600 light years away from where he starts each day with a routine of push-ups, burpees and pull-ups.

By 8, he and other assistants in adjacent pods get the coffee going, put on music and the television, encourage patients out of their cells and get them engaged in a new day.

The early hours, Armstrong said, are the busiest. Breakfast trays are passed out, and patients receive their medications, get checked by psychiatric staff and are prepared for transport if they have court appointments.

While the goal of the mental health assistant program is to stabilize the worst symptoms of mental illness, it also conditions inmates to life inside Twin Towers, where they might live for months or years, struggling with symptoms of their diseases — auditory and visual hallucinations, depression, mania, drug withdrawal — as they are maneuvered through the criminal justice system for offenses that range from misdemeanors like public inebriation or indecent exposure to felonies like burglary, assault, grand theft and murder.

The journey is at best convoluted, each step threatening their health and recovery, said psychiatric technician Tong, and it often begins on another floor of the jail, such as the one a reporter visited earlier this year, where the air was cold and smelled of urine and disinfectant.

A toilet or a sink inside a cell must have leaked; water had pooled on the floor outside. Some windows were smeared with dried substances, food or feces.

An inmate, locked inside his cell, repeatedly climbed onto the top bunk and jumped down and climbed up again. Another stood staring out. Another pounded on the door, calling, “Hey, hey.”

Little wonder that Armstrong is proud of FIP Stepdown for providing inmates with a more humane place to live, but he knows the work of the mental health assistants masks a larger question that no one wants to ask.

“How do you provide treatment in a facility that’s designed for incarceration and punishment?” he said. “That’s like trying to run a diet clinic in a Fatburger.”

Until there’s an answer, FIP Stepdown will have to do.

Armstrong’s day winds down after dinner. Although he isn’t paid for his work, he is compensated with privileges: meals from the officers’ dining room, laptop access, the remote for the television, hot water.

By 8:30, the cells are quiet. He checks in on the other assistants and tries to get on the phone to talk to his mother. He doesn’t watch much television. He’ll work on his writing or study. Sleep comes about 10:30.

More than 20 years of incarceration have left Armstrong thoughtful, modest, circumspect and a little sad. He knows what he misses: the comforts of a home, a woman to hold, his family and friends and a naturally starry sky.

Visitors who arrive at Twin Towers for a tour of Armstrong’s floor are escorted by sheriff’s deputies, and on at least one occasion last year were greeted by Brendan Corbett, former assistant sheriff of custody operations.

“You know the saying, ‘You can’t get well in a cell,’ ” Corbett said. “Well, I call BS on that.”

Corbett had good reason to brag. In 2021, the mental health assistants program caught the attention of the U.S. Department of Justice in its annual report on the Sheriff Department’s compliance with a 2014 consent decree.

After inspecting the jail, an independent monitor cited instances on other floors where inmates were either alone in their cells or handcuffed to tables in the dayroom.

“We observed no therapeutic programming being offered,” wrote Nicholas E. Mitchell.

But his assessment of the FIP Stepdown unit was more promising. Those pods “present a notably different — and far better — living environment” than elsewhere in the jail, and its inmates “were generally more responsive and engaged [and] were better able to make eye contact and answer questions” than inmates elsewhere.

The achievement would be impossible to replicate with mental health staff alone, said Hubbell with the Department of Health Services. Because the assistants sleep and eat with the patients and experience the same reality of incarceration, “the patients feel seen and supported in a way that is personal and often profound.”

“Heartbreaking as it is, for people who may have suffered abuse and rejection their entire life, it could be the first time someone has felt that level of personal investment from another human being,” she said.

That investment means long hours and a steady commitment from the mental health assistants, who juggle the demands not only of the job but also their own incarceration.

At a recent Board of Supervisors meeting, Solis sought to address this inequity with a motion to study the possibility of compensating assistants with “wages, food and time credits,” with academic certification and a provision that some of their time in jail would serve for their time in prison. The motion passed.

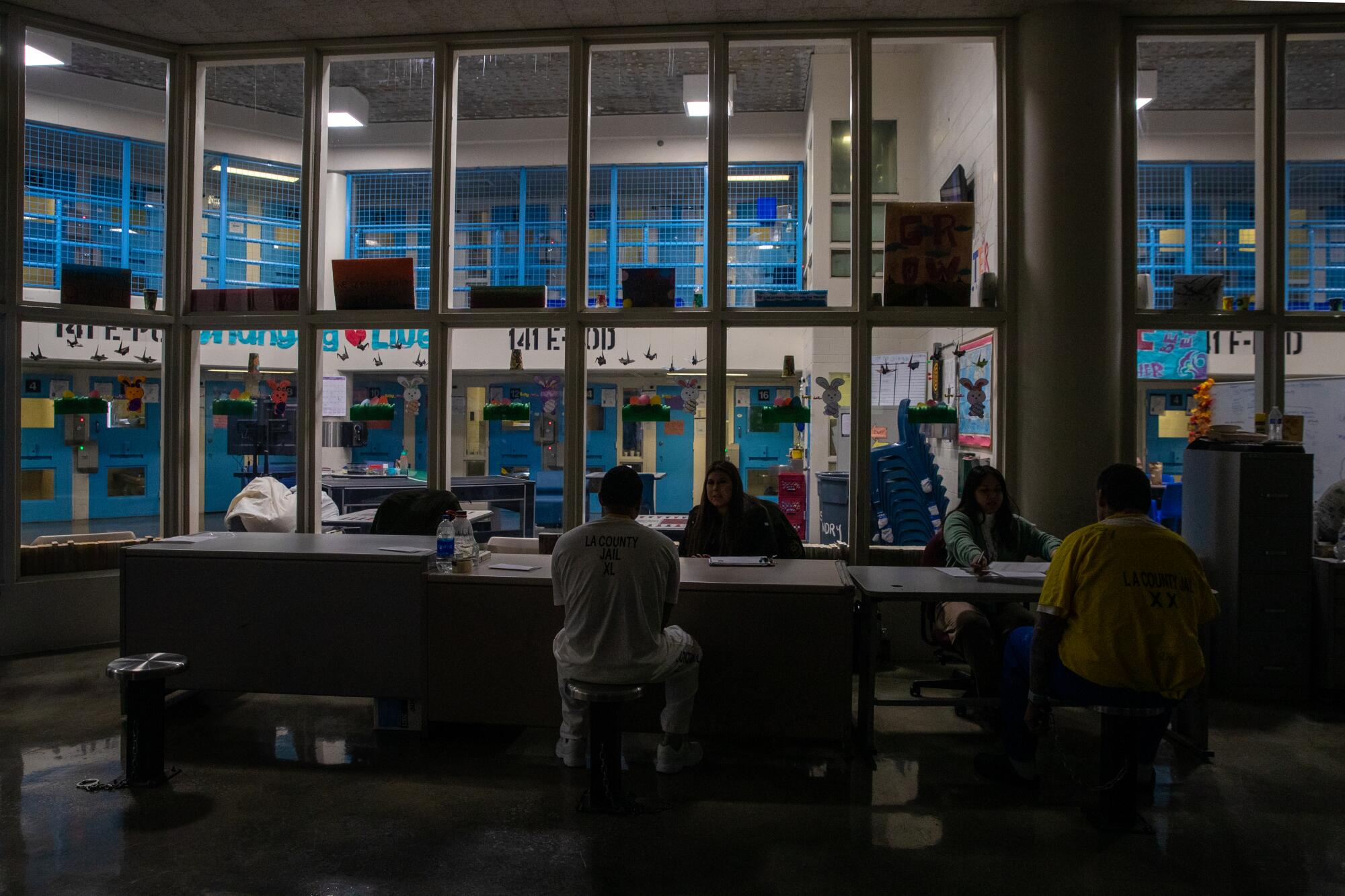

On a Thursday morning in the spring, a Times reporter and photographer watched as Armstrong finished up a karaoke session in one of the pods.

Banners hung on the walls of the dayroom exhorting “progress” and “love each other.” Artwork by patients hung on a few inside windows. The floor had been painted with planets and stars on a dark background.

Patients performed songs by Michael Jackson, Smokey Robinson, Bruno Mars and Phil Collins, and the judges — three patients seated in front “American Idol”-style — voted with raised hands.

“And the winner is,” Armstrong declared with a dramatic pause, “Smokey Robinson.”

Applause filled the room, and Smokey stood for his encore. Without a trace of irony, he selected “Hotel California,” and the audience hung on to the performance to the very end.

“Relax,” said the night man.

“We are programmed to receive.

“You can check out any time you like,

But you can never leave.”

Since arriving in Los Angeles in 2016, Armstrong has been taken periodically to the Criminal Courts Building for pretrial conferences. Each has begun and ended the same way.

Handcuffed, he is escorted into the courtroom and sits at the defense table. He smiles when he sees his mother, who has attended every conference. His attorney, Albert DeBlanc, addresses the judge, Ronald Coen.

“My client wants more time to think,” DeBlanc said at a recent appearance. Coen and Deputy Dist. Atty. Carmelia Mejia agreed.

Armstrong stands and walks back into the holding area. Time in prison and jail has taught him patience.

Since returning to Los Angeles, he has watched as Gov. Gavin Newsom imposed a moratorium on the death penalty, as county voters elected George Gascón as district attorney and as the pandemic shut down the courts — all of which put a pause on a more immediate resolution.

He also knows that his attorney and the office of the district attorney have been negotiating and that he has a decision to make: to accept a plea deal that could put him in prison for the rest of his life or stand trial for a second time on the 2001 charges and either win or lose his freedom. Neither his attorney nor the district attorney’s office would comment.

Mindful of the sensitivity of his case, he keeps his deliberations private but lives each day wondering what he could possibly do to change the judgment of society.

“Part of this story is about redemption,” he said. “What is redemption, and how is it recognized? A lot of us in prison would like to know.”

His question is more than personal. All of the mental health assistants face similar charges and have been chosen because their cases take a long time, which gives them more time in the jail. But as Armstrong explains, the program also gives them an opportunity to demonstrate that who they are today is not who they were in the past.

As he wrestles with his choices, he feels pressure to keep expanding the program, especially after the Board of Supervisors’ vote in June. Confident of what it has accomplished — for patients, inmates, deputies and himself — he hopes the program might be adopted by jails and prisons throughout the state and wants to leave nothing to chance.

“One step can mess this up,” he said. “We have to make sure that doesn’t happen.”

At the end of the last karaoke session, Armstrong took a moment to ask the patients what they like about being on this floor. Some held back, but others were eager to speak.

“I’m grateful for the extra food we’re provided,” said one.

Armstrong helped put the answer in context for everyone: Many patients have been homeless, scraping by with little to eat.

“It will be important one day to walk away from this facility with healthy habits,” he said. “We try to provide hot food for everyone because if we can alleviate the little things that bother us, then the bigger things that bother us are more tolerable.”

Another man raised his hand. “It is like family in here,” he said. Together, the patients watch movies, participate in group activities, play games with one another.

“We try to create a good environment,” Armstrong said. “With so many people who are incarcerated, these places can be overwhelming. The goal here is to accelerate your progress and to help you make the transition out of here.”

The discussion picks up. “We’re given opportunities to practice being on the outside, being courteous and knowing that things will get better,” said another.

“We want to create a normal lifestyle,” Armstrong added.

“With mental illness, it takes trust,” said one man, “and this place makes you more receptive to accept the help you need.”

For a moment Armstrong seems at a loss for words. Then he finds them.

“Accepting your own vulnerability,” he said, “allows you to relate to others.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.