“I’m sorry,” the skinny young man said again and again like an incantation, as if apologizing enough times would make his antagonists disappear. His words only enraged them further.

Earlier that day, while protesting outside the Pomona Police Department for a friend to be released, the group of a dozen or so had chased the man away after he mistakenly blamed them for closing down the front desk. An hour later, the man returned and threw a bottle at them, triggering them to follow him home.

“Get on your f— knees, and apologize, b—!” yelled Edin Alex Enamorado in the video played by a prosecutor in a Victorville courtroom last week.

The man exited his car and walked a few steps. He knelt and clasped his hands. “I’m sorry,” he proclaimed one more time. He got up and offered to shake Enamorado’s hand. Enamorado scornfully waved him off.

“We let you live, homie!” a woman yelled as the man returned to his car. Someone threw a plastic bottle at his face. Another sprayed something as he drove off.

The prosecutor hit the pause button. The energy in the packed courtroom dropped. A few feet away, Enamorado and six of his friends who had badgered the man sat with their hands shackled to their orange jumpsuits.

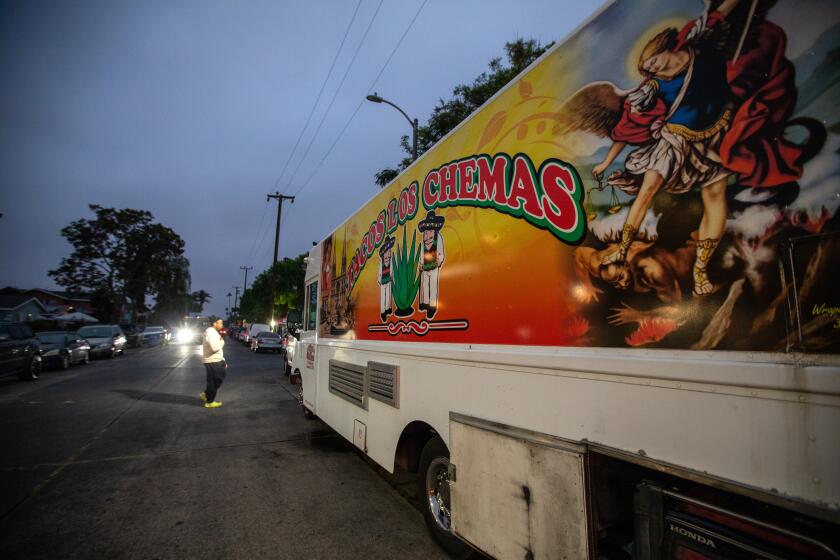

A rash of robberies targeting food trucks and stands across L.A. — including six in mid-August — has had a chilling effect on the industry.

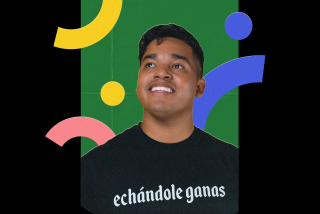

In his years-long battle to combat harassment and violence against street vendors, Enamorado has amassed hundreds of thousands of online followers who cheer on his virtual and in-person wars.

A call, a text, a tweet, a DM from a distressed vendor — that’s all it takes for the Inland Empire resident to unleash social media storms that are equal parts “To Catch a Predator” and the Food Network.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

Though he made his name defending street vendors, he has unleashed his power for other causes, as in Pomona. Sometimes, his acolytes confront alleged offenders at their homes, their places of work, in public. Other times, they swarm social media accounts until the owner switches to a private setting or deletes it.

To fans, Enamorado is an archetypal Latin America avenger, revered as much for standing up for long-oppressed people as for embarrassing the powerful. To detractors, he is an agent of chaos, a sinister version of Loki, the charismatic God of Mischief from the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

On Dec. 14, San Bernardino County sheriff’s deputies arrested Enamorado, his fiancée Wendy Lujan and six others on felony charges of conspiracy, assault, false imprisonment, kidnapping and other offenses for their role in three alleged attacks during rallies in September, including the one involving the man in the video. Enamorado was also charged with being a felon in possession of a firearm. He and all but one of the other defendants are being held without bail.

I’ve been following Enamorado since he began his street vendor activism about three years ago, and I’ve been interviewing him over the last few months. I’m not surprised at his predicament. It was inevitable.

A judge says San Bernardino County can try the case against activist Edin Enamorado and his allies, which also involves incidents in Pomona in L.A. County.

As his reputation as an Internet folk hero grew, his opponents closed in. By the time of his arrest, TikTok and Instagram had shut down his main accounts. Arrests were beginning to pile up for his in-your-face actions. Targets of his ire — including Fontana Mayor Acquanetta Warren, who pushed for increased regulations against street vendors and said undocumented immigrants needed to learn English — were pursuing restraining orders against him. Online commenters were posting details from his rap sheet.

Yet Enamorado kept at it. He reminds me of a tragic Greek hero, who does good deeds to redeem the bad but can’t quite escape his worst foe:

Himself.

**

In September, about two months before his most recent arrest, I was having a carne asada torta while Enamorado sipped on a Sprite at a Mexican restaurant in Lincoln Park.

He was getting results, and national attention, that year — even an appearance on the Cinco de Mayo episode of “Dr. Phil.” After he launched social media campaigns, two security guards in San Jose who had kicked over a strawberry vendor’s stand lost their jobs. A security guard at SoFi Stadium was fired after allegedly tipping over hot dog carts after a concert. A Santa Barbara woman who called a construction worker a “Tijuanan” was arrested for battery and trespassing.

Enamorado was also offering vendors free security through a network of volunteers, as well as licensed guards he paid out of his own pocket. He set up a nonprofit to help pay attorney’s fees for vendors and hold free classes on applying for business licenses.

Of average height but strapping, Enamorado is polite — even gentle — to anyone he’s not lambasting. His soft chuckle and soft eyes take the edge off some of the tattoos on his arms — a “323” to signify his L.A. roots, the pairings “Destiny/choice” and “love/hate” to remind him of the thin line between them.

I asked what motivates him.

“At the beginning, it was anger,” said Enamorado, 36, who worked as a political consultant before his recent legal troubles. “But anger only goes so far.”

Outside, Lujan was meeting with a flower vendor who had been robbed two nights earlier of $24,000.

Enamorado didn’t flinch when I told him that some people who appreciate his intent feel he frequently crosses the line between reasonable dissent and vigilantism.

“I’m on my best behavior,” he replied matter-of-factly. “We’re not punching people. We’re exercising our 1st Amendment rights. We’re even educating the police about what the law is. If you’re going to talk about freedom, and that freedom doesn’t fit your agenda, what kind of country are we?”

I can’t believe this still needs to be said, but please, for the love of whatever you consider holy, leave street vendors alone.

Enamorado isn’t the first person to seek justice for street vendors via social media —but he’s the genre’s Michael Moore. His reels, many still available online, are master classes of comedy and outrage.

He usually starts by sharing videos of an altercation that he remixes with graphics, voiceovers and a public plea to identify the offenders and hold them “accountable.” Once names emerge, he discloses them in a follow-up post, along with social media handles and sometimes even the work and home addresses of the perpetrators.

Next: direct confrontations, livestreamed, in which the former aggressor usually turns into a blubbering mess, and Enamorado occasionally gets arrested for protesting too loudly. Then come “sell-outs,” in which hundreds of people support a victimized vendor by buying all their food for the day, followed by a coda with Enamorado ridiculing the instigator, lecturing law enforcement for not protecting vendors, and proclaiming victory.

“What Edin’s message is, is ‘If you see something, do something,’ ” said Bill Esparza, an award-winning food writer who has reported on street vendors in Los Angeles for more than a decade. We spoke a few weeks after Enamorado’s arrest. “There needs to be some protection for these sellers. The police aren’t going to do it.”

He compared Enamorado to Curtis Sliwa, the founder of the Guardian Angels who was also both praised and criticized for taking the law into his own hands.

“Edin is doing something that we feel we all want to do,” Esparza added. “It takes tremendous courage to do what he’s doing.”

**

Enamorado was born in Guatemala and came to the U.S. as an infant. Whenever gunshots rang out near their Cudahy home, his mom threw him to the floor with the excuse that the neighbors were playing a game. Raised a Jehovah’s Witness, he eventually fell into gangs, dropped out of school in 10th grade and was homeless for a while — a history he has spoken about openly on podcasts and his Instagram Live.

“If you think I’m rough, my brothers were rougher,” Enamorado said. “But my brothers changed, and they inspired me to really think about what I was doing with my life.”

In 2009, Enamorado sued the Cudahy Police Department, claiming an officer assaulted him. The lawsuit went nowhere after the department disbanded, but he soon got involved with residents protesting civic corruption across southeast L.A. County. That led to a career in organizing — a stint with the public policy nonprofit William C. Velasquez Institute, regional field representative for Bernie Sanders’ 2020 presidential run, Cudahy parks commissioner, youth coach for the Dodgers Foundation.

In January 2021, Enamorado saw an online video of men robbing a fruit seller in Long Beach.

“My mom ... would leave me at home while she went out and preached,” he said when I asked why he shifted his energies toward food vendors. “So when the paletero came, it was my only chance to have something extra.”

The attack against the vendor unlocked feelings of guilt that had long haunted Enamorado. In high school, his girlfriend was killed by his close friend after a gun accidentally went off. An older brother died in 2015 after jumping off an overpass near the 110 Freeway. In 2018, Enamorado’s father — a mobile mechanic — was carjacked and robbed of his earnings but didn’t immediately tell Enamorado, fearing that his son would be consumed by rage.

“I felt a lot of responsibility for not being able to help them all,” Enamorado said “Even when I was a kid, I felt guilty about 9/11. I felt I could’ve helped somehow.”

After seeing the Long Beach video, he visited the vendor, Victor Cortes.

“He said he was an activist and said he wanted to help,” Cortes, a native of the Mexican state of Veracruz, told me while setting up for the day. “I was very grateful — I still am. Imagine! A guy helping you, just because. Helping all of us.”

Once word spread, Enamorado’s phone never stopped buzzing — he heard both from those seeking help and those who wanted to help. After his arrest, supporters raised money to pay the legal fees for him and his co-defendants, nicknamed the “Justice 8.”

But for those who have experienced it, Enamorado’s wrath can be life-altering.

Susan Lopez once admired his videos, thinking it was “awesome that he stood up for these people.”

In August, she came across a video of his that captured her threatening to call immigration officials on a corn vendor who lived in a garage at the home of her elderly immigrant parents. She claimed it was because the man had sexually harassed her and refused to vacate.

The following day, Enamorado was at Lopez’s house “full on screaming and yelling” as he presented her with a temporary restraining order filed against her by the vendor, Efren Marquez.

She was familiar with Enamorado’s tactics, so she knew what was coming next.

“His aggression and violence — I didn’t see it that way, until being on the receiving end,” said Lopez, 47, who lives in North Hollywood.

Enamorado led a sell-out of Marquez’s corn cart outside Lopez’s parents’ home. She received harassing phone calls and texts after someone posted her number on Instagram. She resigned from her job of 10 years at a medical office after people protested outside, then went into hiding for two months along with her daughter.

“He cost me a lot of mental anguish, he cost me friends and acquaintances, and the neighbors don’t talk to us anymore,” Lopez said. “And he harassed my parents.”

She filed for a restraining order against Enamorado, which a Los Angeles County Superior Court judge granted in October. For five years, he is prohibited from getting within 100 yards of her, trying to find out where she is or posting anything about her online.

Enamorado didn’t attend the hearing.

“That threw me for a loop,” Lopez said. “I saw him doing an interview that day. That was more important to him than this? Maybe he thought, ‘They’ll drop it. She doesn’t have enough evidence.’ Maybe he didn’t know what his followers were doing to me.”

Lopez paused. “Maybe he didn’t care.”

Street food vendors have always been the working poor, scraping by in jobs that are the envy of no one. Aren’t those the hustlers that cities should want to protect and uplift?

I was weighing the good and bad of Enamorado long before his arrest.

He was frequently rude and excessive, but I rooted for him and defended him to family, friends and colleagues. Society has mistreated street vendors for far too long, I argued, so Enamorado’s unapologetic approach brought them some level of public deliverance.

The evidence presented against him and the others during the five-day preliminary hearing last week convinced me that the charges were prosecutorial overreach.

Witnesses — Pomona police officers, San Bernardino County sheriff’s deputies and detectives — were unprepared and unconvincing. Most admitted under cross-examination that their investigation consisted of watching a single video of the incident, despite there being many.

Defense lawyers introduced other footage that contradicted the cops’ testimony. Deputy Jonathan Ortega, who was on the scene at a Sept. 24 incident in Victorville, originally stated that Lujan had pepper-sprayed the victim.

When video showed that she had instead thrown a weak punch, Ortega replied, “If it’s not [Lujan], I must’ve mistaken her for somebody else.”

Prosecutor Jason Wilkinson relied on videos shot by Enamorado and others to argue that the defendants practiced little better than “sensationalism,” “ritualized harassment,” “preconceived vigilantism” and a “confrontational approach.”

At a news conference the afternoon of the arrests, San Bernardino County Sheriff Shannon Dicus had blasted the group’s advocacy as “clickbait for cash.” A poster featuring photos of the eight detainees was arranged like a Mafia family tree, with Enamorado at the top.

“Videos of the ‘truth’ were manipulated and put out to the public to make it look like an underserved community was being represented,” Dicus said. “Kinda like a Robin Hood-ish. When in fact there was felonious activity behind this.”

Dicus’ insinuations never came up in court last week.

Enamorado’s attorney, Nicholas Rosenberg, cast his client as an activist in the vein of Cesar Chavez.

“What they’re trying to show is that Edin is the leader of the pack,” Rosenberg said after court one day. “But confrontational isn’t criminal.”

I wonder why San Bernardino County officials are prosecuting two incidents that happened in Pomona, which is in L.A. County, amid the one that did happen in their jurisdiction. I also agree with defense lawyers that prosecutors have a vendetta against Enamorado and want to shut him down altogether.

In addition to the Pomona police station and Victorville incidents, the charges stem from two other incidents involving shoves, punches, pepper spray and invective. From what I saw, all the alleged victims made provocative moves that led to their beat-downs.

As I heard and saw hours of testimony, the most damning — and damaging — charge against Enamorado wasn’t listed on the court documents. It wasn’t even a crime. It was hubris.

Continuing to attack people after the fight was over, as video after video screened in the Victorville courtroom showed, was not going to end well for Enamorado and the other assailants. Enamorado carried pepper spray in public, even though he was prohibited from doing so because of a 2014 grand theft conviction. As a convicted felon, he was also prohibited from possessing a gun — yet he documented himself on Instagram shooting at a firing range.

I’ve seen Enamorado tiptoe on sidewalks to avoid stepping on lawns — at the same time he was hounding the home’s residents. For someone who pays attention to such details and who can spout off laws with the ease of a public defender, his moves in the months leading up to his Dec. 14 arrest are shockingly sloppy. He has become a street-smart Icarus too wrapped up in his own world to bother with real-life consequences — either that, or he views himself as a martyr.

When I saw the video of Enamorado forcing the man to kneel, I thought of the proverb popularized by Spider-Man: With great power comes great responsibility. Being merciful, even to your enemies, goes a long way.

Enamorado doesn’t deserve the hammer that law enforcement has dropped on him. But he sure ran toward it, then dared them to swing.

To his followers, he and the rest of the Justice 8 are political prisoners. Dozens have shown up for every court hearing, traveling for hours and staying all day.

Whittier resident Lorenzo Aguiar helped run a sell-out on Jan. 9 in Long Beach and plans to hold more. Enamorado’s videos “encouraged me to do something,” the 42-year-old security guard said.

“That’s not them,” Aguiar said of the prosecution’s portrayal of the defendants. “If you really go out and support, you can see the true Alex, the true Justice 8.”

One morning, a man in a blue Pendleton-style jacket and gauges in his ears mistakenly showed up, thinking his own hearing was in the same courtroom as Enamorado. He stayed and watched for a good while.

“I saw his IG Lives, and the cops always change what they say they saw,” he said outside the courtroom.

“Edin stands up for raza,” added the man, who declined to give his name.

Before announcing which charges had sufficient evidence to go forward, Judge Zahara Arredondo described herself as “very sensitive, very empathetic” to the plight of street vendors.

But, she said, what the Justice 8 did wasn’t in line with those commendable goals — especially not making a man kneel and grovel.

“Seeing it on video,” the judge said with curled lips and furrowed eyebrows, “is to me one of the most offensive things possible that could be done to a person.”

Arredondo, a former public defender, dropped two felony charges against Enamorado. He still faces 13 other felonies and one misdemeanor and remains in jail without bail, with another bail hearing scheduled for Friday.

As the hearing adjourned, Enamorado suddenly spoke. From his cell, he had recorded voicemails urging followers to be respectful in court. Not anymore.

“This is not fair!” he yelled. “You allow murderers to get bail!”

Shouts of “Y’all f----n’ racists!” and “Free the Justice 8!” filled the courtroom. Deputies ordered everyone out, all the way to the outside and the cold, windy afternoon.

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.