Neighbors knew Ruby Scott as the petite old lady who swept her driveway every day, who pushed her broom up and down the street even if she just moved the trash to a different place.

That anyone would want to harm Miss Ruby, 81, seemed unthinkable. Yet someone stabbed her all over her head and hands and smashed her skull in the converted garage in Watts she called home.

Seven months after her death, the Los Angeles Police Department announced the arrests of three young brothers who lived on her block.

“Old-fashioned police work” and some physical evidence led to the killers, Det. John Zambos told reporters in front of the LAPD’s Southeast station on March 8, 2002.

But the brothers — ages 13, 14 and 15 — were eventually released because their blood and fingerprints didn’t match samples from the scene.

And there, the investigation ended.

Ruby Scott’s file remained classified as “cleared by arrest,” even with no suspects. Years passed with not a single fresh sheet of paper added to it.

The regret never eased for Scott’s grand niece, Tanya Broomfield, who had urged her aunt to move in with her.

Watts was all Scott had known since leaving the tiny Louisiana town of Castor as a young woman. Her church. Her bus routes. The driveway she kept spotless. The Dodgers games she listened to religiously on the radio. She wasn’t going anywhere.

Broomfield’s younger half sister, Pamela Clark, had a different kind of regret. She hadn’t visited Aunt Ruby much.

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

But Clark grew into a role as the family historian. The one who pushed for answers.

Two topics were off-limits for Aunt Ruby — her life in Louisiana and the recipe for her lemon Jell-O cake.

She wore high heels and flared dresses with aprons when she cooked for the nieces and nephews who came over every Sunday, though her food was decidedly down home — red beans and rice, cornbread.

“Oh my God, that woman could cook. She made biscuits that would melt in your mouth,” Broomfield recalled. “And she used nothing but butter.”

The town of Castor in the Jim Crow era was too small for someone who always accessorized with fancy earrings in photos. Scott joined the many Black migrants from the South starting new lives in Los Angeles.

Here, there were still limits to what a Black woman could do. She cleaned white people’s houses. After divorcing her husband, she lived for a time in the Jordan Downs housing development, Broomfield said. Her son, Charles Ray Scott Jr., died in 1987 at age 40.

Aunt Ruby encouraged Broomfield to become a beautician, and she would sit for hours while her niece shampooed, pressed and curled her hair.

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

“That water’s going to be so hot! I say, ‘God, now that’s not too hot, Aunt Ruby?’ ‘No, sister.’ I’m gonna tell you. I can hear her voice,” Broomfield said.

Aunt Ruby was full of advice about Broomfield’s then-husband. But if Broomfield ever asked about Castor or their family there, she clammed up. Family lore had it that Ruby’s brother-in-law killed his wife — Ruby’s older sister — then fled with his children to Chicago.

For Clark, nearly 20 years younger than her half sister, Aunt Ruby was a name that sometimes surfaced in family talk. Even after she sat down with Ruby for a formal introduction as an adult in the early 1990s, she rarely joined the Sunday dinners.

1

2

3

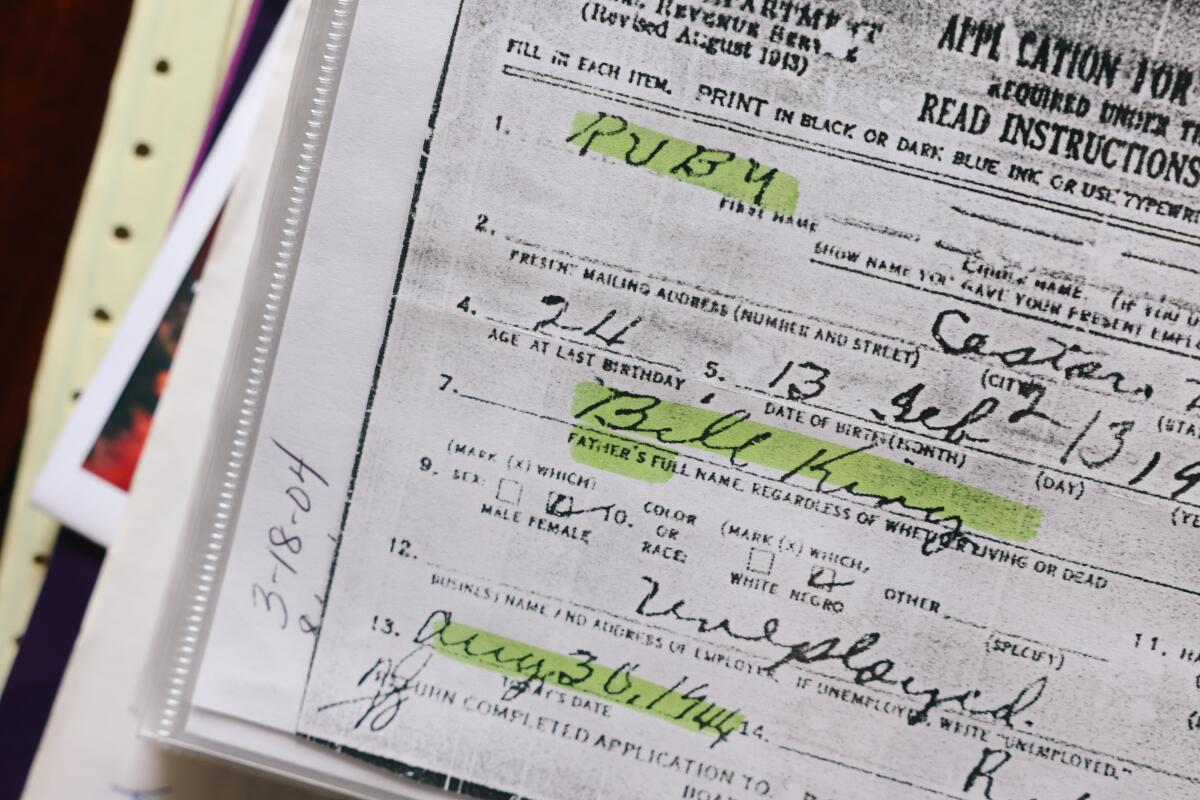

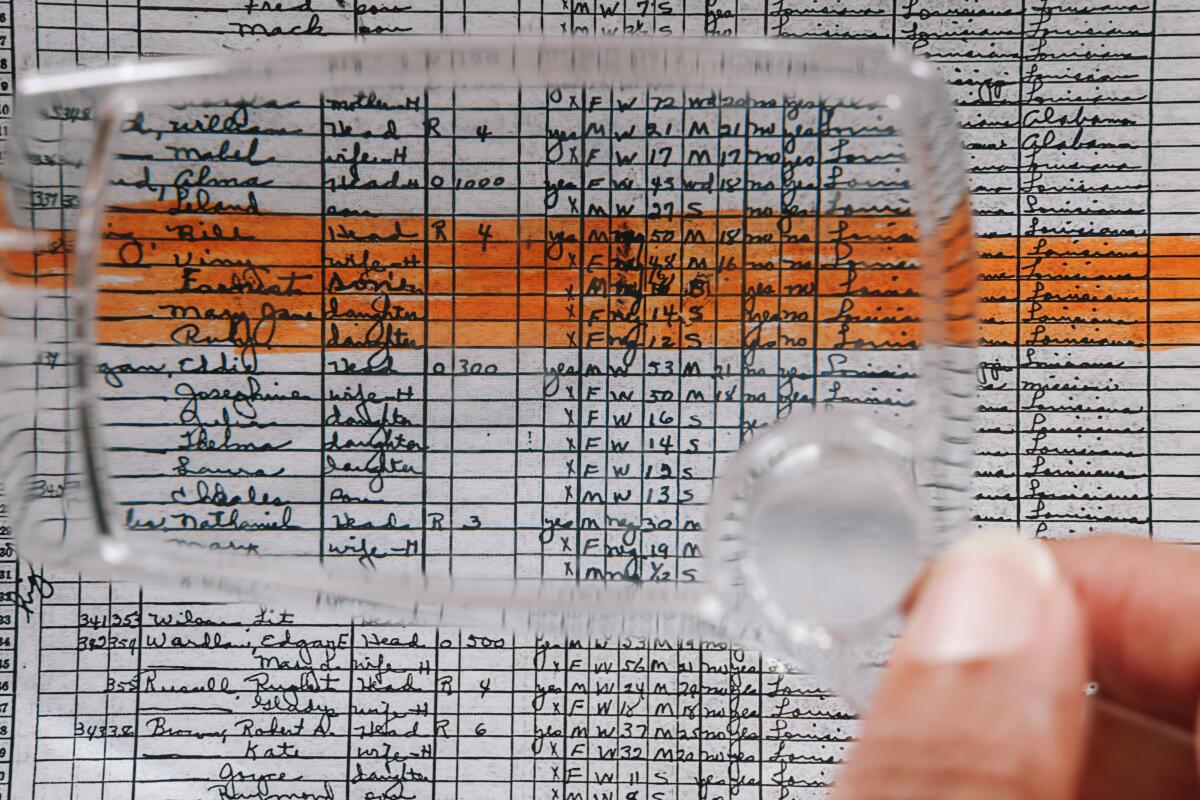

1. Pamela Clark has a binder from her genealogical research, including this application for her great aunt’s Social Security card, at home on Sept. 11, 2023, in Los Angeles. 2. The census record is viewed through a magnifying glass. 3. Clark uses a magnifying glass to see her great aunt’s name in the census record. (Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

Weeks before Aunt Ruby was killed, Broomfield drove her to Riverside County. It was just Broomfield and her husband in a three-bedroom house. Ruby could have her own room and bathroom. Convincing her to leave Watts would take time, but that visit was the first step.

Ruby’s purse had been snatched several times. There was graffiti on the vacant house next door, and a neighbor had warned about the kids who partied there. Still, Broomfield never thought the danger was so imminent.

“They went in there on her before I could get to her,” she said.

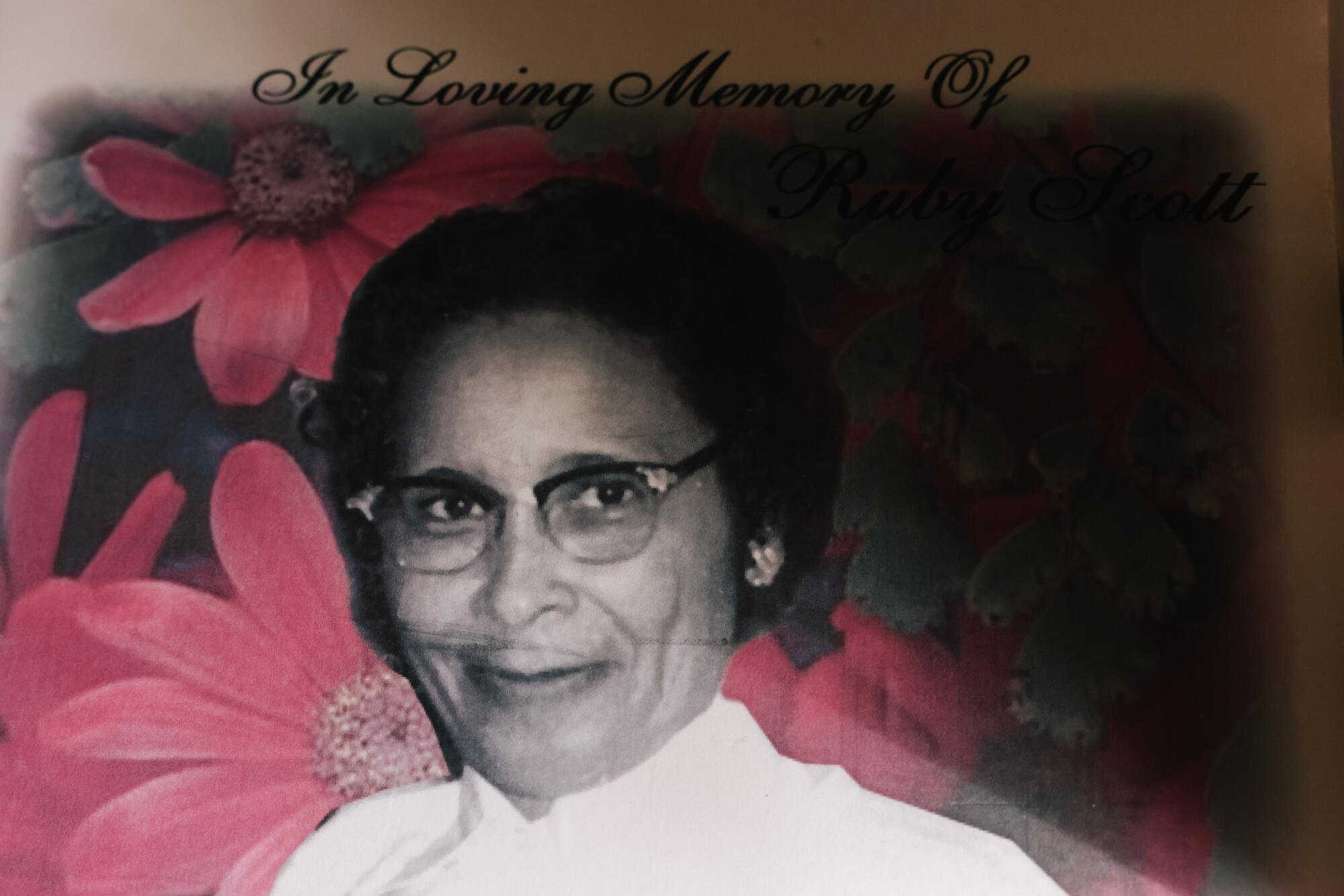

In the photo on her funeral program, Scott wears a white blouse and a white cardigan, her hair a smooth helmet. There is a schoolmarmish sternness behind her half smile, but her eyes are wryly amused.

“Airship, we’ve got two officers down, 106th and Wilmington,” an LAPD officer said calmly into the radio.

Another officer dragged a man in a plaid shirt and dark pants, lying face down and bleeding heavily from the head, from the curb into the street and handcuffed him.

Sitting on the ground beside a patrol car, an officer who had been shot in the leg described what happened: “We rolled up. We had two guys running. One guy had a shotgun. When we stopped, he looked at us. He said, ‘Who’s that?’ and bam, he just shot at us.”

The Dec. 13, 2003, scene was captured in a documentary about violence in South L.A. reported by Peter Jennings of ABC News.

Javier Vieyra, the man who was shot in the head in the gun battle with the officers, had a loaded .38-caliber revolver on him, according to the LAPD. Sergio Diaz, who had fired at the officers with a 12-gauge shotgun, fled and was later found hiding in a trash bin.

The two officers who were shot survived and received Purple Hearts from the LAPD. Vieyra, then 19, was declared brain dead and put on life support, later spending 266 days in the Patton state mental hospital, according to court records. He eventually recovered enough to go on trial, observing the proceedings from a wheelchair.

He had once lived in Watts, near where the shootout happened and about a half mile from Ruby Scott’s house.

In June 2008, he pleaded no contest to assault with a firearm on a peace officer and was sentenced to eight years in prison.

As required by state law, he gave a blood sample so his DNA could be matched with unsolved cases.

***

As David Ross flipped through the murder book in March 2017, he noticed the streaks of blood in a Polaroid photo of Ruby Scott’s bathroom sink. Tests had determined that it wasn’t her blood.

So whose was it?

All 5 foot 3 and 133 pounds of her had fought back. She had defensive wounds on her hands. The killer had stabbed her repeatedly with a knife that grew bloody and slippery. He could easily have cut himself.

Ross, a cold case detective with South Bureau Homicide, was picking up the threads more than 15 years later as he worked his way through a list of unsolved cases. He called the LAPD’s DNA lab.

The criminalist unearthed a DNA hit letter from 2008. It had never been added to the murder book and never been investigated by detectives.

The name on the letter: Javier Vieyra.

Clark was at a work conference in Bakersfield when Ross called to say that he and his partner, Bertha “B” Durazo, were taking over the case.

The baby sister who had blown off the family dinners became the main contact with the detectives. Well before Aunt Ruby’s death, she had developed a fascination with the past and had been researching her family tree, tracing the Scotts all the way back to slave times.

She had so many questions — not that Aunt Ruby would have told. But she felt robbed of the chance to ask.

“As an adult, you look back, and you look at the things that you should have done,” said Clark, 59, who works for a state government agency and lives in South L.A. “So that’s, I guess, why I’m pushing so hard now for her. Because, you know, at least, she didn’t get to know me, but she’s watching me from heaven.”

Ross, a former Marine with intense blue eyes and white hair buzzed military-style, asked Clark for photos of her great aunt. The previous detectives hadn’t included any in the file. Didn’t they care to know what she looked like?

Not only was Vieyra’s blood in the sink, Ross found, but his palm print appeared on the bedroom wall and the sill of the window that the killer had broken to enter the house.

Ross and Durazo’s commitment to cold cases — and to the families still mourning after decades — put them at odds with some LAPD brass who wanted to put resources elsewhere. They were angered by what had happened, or hadn’t happened, immediately after Scott’s killing.

“The Los Angeles Police Department’s South Bureau Homicide currently staffs a total of 7 detectives that are exclusively assigned to Unsolved Homicide cases,” Capt. Kelly Muniz, commanding officer of the LAPD’s media relations division, said in an email. “The Department has no further remarks on this matter.”

Investigators had left the crime scene unsecured before they went back on Aug. 3, two days later, and found a 7-inch kitchen knife that Ross says he believes was the murder weapon.

In the murder book, a note about the blood in the bathroom sink was dated Aug. 1, 2001 — the day Scott’s body was found by a neighbor. But the Polaroid of the sink was time-stamped Aug. 3, Ross said, indicating that detectives may not have noticed the blood until then.

Valuable time had been lost as the three young brothers languished for months in juvenile hall. They had been implicated by a 15-year-old witness who, years later, told Ross and Durazo that LAPD detectives had browbeaten him until he told a false story. On a recording of the interrogation that Ross and Durazo studied, Zambos and his partner, Mark Hahn, pressed the teenager in what Ross described as a “coercive interview,” accusing the boy of lying and saying he would feel better after he got it off his chest.

There were leads that could have been followed, according to Ross. Detectives could have interviewed the kids who hung out in the vacant house next door, drinking and smoking weed, who scattered whenever they saw the old lady who constantly swept the driveway.

It was a busy time for detectives, with nearly 600 homicides a year in Los Angeles, compared with fewer than 400 in recent years. Fresh cases demanded attention.

And a file erroneously marked “cleared by arrest” wasn’t going to be touched.

“And then it all falls apart when the evidence doesn’t match. So what do you do now?” Ross said. “So whoever that person was should have gotten people together and said, ‘OK, so we had the wrong kids. So what do we do in moving forward to get the right people? What else can we do on this case?’ And that just didn’t happen.”

Then there was the DNA hit letter, matching Vieyra’s blood to the blood in Scott’s bathroom sink. The letter should have been put in the file, and detectives should have zeroed in on Vieyra, back in 2009.

Zambos, who had hailed old-fashioned police work in announcing the three brothers’ arrest, is retired from the LAPD and did not return calls and text messages seeking comment. Hahn, who worked the case with Zambos as a young officer and is now a detective in South Bureau Homicide, declined to comment through his supervisor, Capt. Jamie Bennett.

Vieyra, who was 16 at the time of Scott’s slaying, lived nearby and, according to Ross, belonged to a now-defunct gang, Killing Mob Watts.

The motive might have been burglary, Ross said. But the house was a mess after Scott’s struggle with the killer and whatever else the killer did while there. Her family never reported that anything was missing.

On Aug. 17, 2017, a little more than 16 years after Ruby Scott’s slaying, Vieyra was arrested in Bakersfield and brought to Los Angeles.

The case stayed in juvenile court for nearly three years before prosecutors won their bid for Vieyra to be tried as an adult.

At a Men’s Central Jail visiting booth last August, Vieyra wore brown scrubs and spoke through the Plexiglas from a wheelchair.

He said he didn’t know Ruby Scott and didn’t remember whether he killed her. He didn’t know why his blood was in Scott’s home or why he was arrested for the crime. He said he lived in Watts at some point, on Wilmington between 104th and 105th, and was in and out of juvenile hall around the time of the slaying.

“They should have arrested me for this when I was in prison. Why did it take them so long?” he said.

***

Clark thought the sentence was way too short. So did Ross and Durazo, who had recently retired from the LAPD because they felt that cold cases such as Scott’s were not getting enough attention.

But it was prosecutor Rosalba Gutierrez’s call. With the passage of time and the issues with the investigation, the deal was the one they were going to get.

On Nov. 13, Vieyra agreed to plead no contest to voluntary manslaughter, second-degree robbery and first-degree burglary. Credit for the time he had served since his arrest would shave about six years off his sentence of 14 years and four months.

Gutierrez referred questions to the L.A. County district attorney’s press office. Vieyra’s attorney, Thomas Lee, declined to comment.

In Ross and Durazo, Clark had found detectives who cared as much as she did and who always answered her calls. But something she badly wanted to know had never emerged from their investigation: Why?

At a hearing on Jan. 16 to finalize the sentence, Clark addressed Vieyra, who sat in a wheelchair next to Lee.

“Maybe you were in that house. Remember that, Javier? Did you and your friends laugh at her? Did you call her old lady? ... How did you kill her?”

Clark held up a photo of her great aunt.

“Do you remember her? She fought you ... What trauma happened to you?” Clark said, her tear-choked voice rising.

Vieyra responded: “LAPD.”

The judge cautioned Clark to watch her language. She continued in a calmer tone.

“The brutality in which she died. That will haunt me,” she said. “I hope you remember taking her life. I hope it haunts you.”

Times staff writer Brennon Dixson contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.